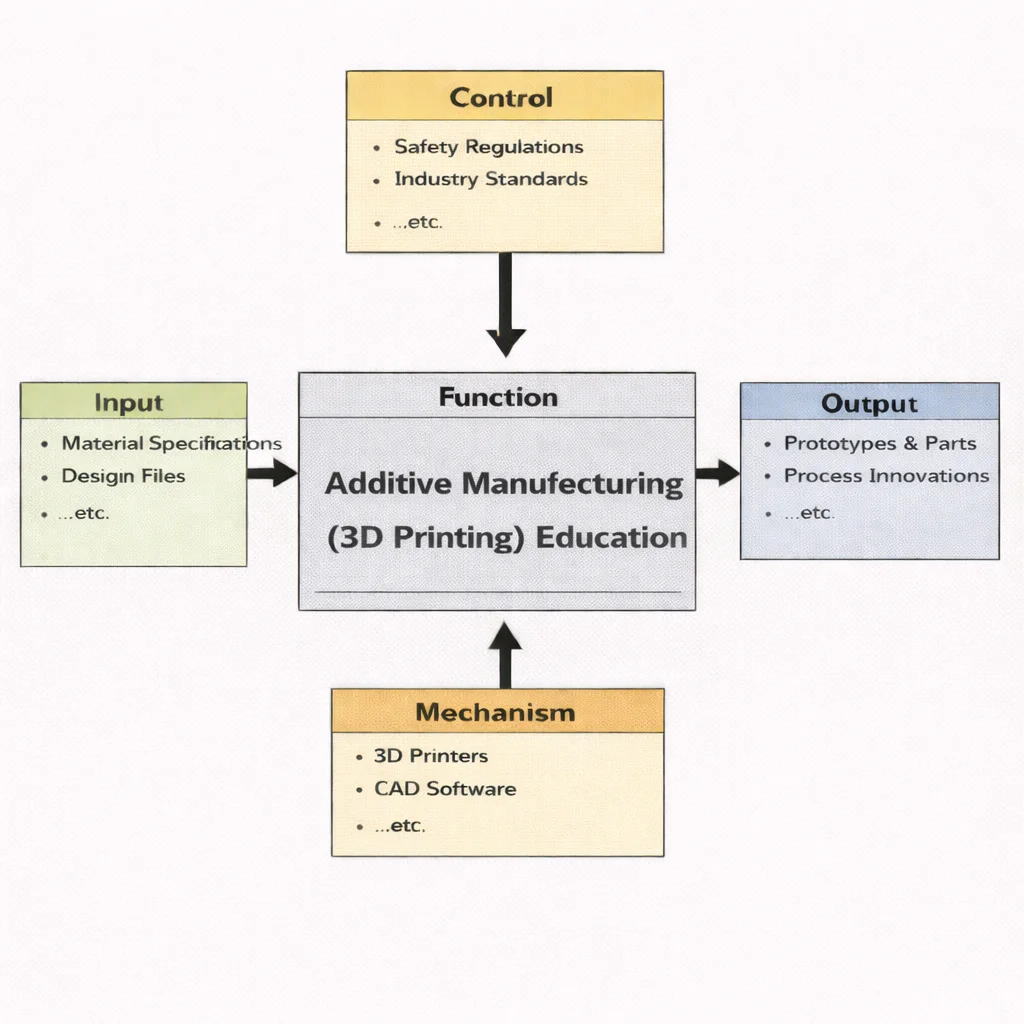

IDEF0 diagram shown here makes the purpose of Additive Manufacturing (3D Printing) immediately clear: it trains students to turn ideas into objects through a repeatable, testable workflow. Students begin with design intent—files, material choices, and constraints—then work within safety and industry requirements that shape what “good printing” actually means. Using printers and CAD tools as their hands and eyes, they learn to prepare models, tune parameters, print, inspect, and iterate. What emerges is more than a printed part: it is capability—students develop the mindset to prototype quickly, diagnose failures calmly, and improve both product geometry and the manufacturing process itself.

This IDEF0-style diagram frames Additive Manufacturing (3D Printing) Education as a structured learning system. On the left, Input highlights what learners start with (material specifications, design files, …etc.). Above, Control sets the boundaries for responsible practice (safety regulations, industry standards, …etc.). At the bottom, Mechanism names the enabling resources (3D printers, CAD software, …etc.). On the right, Output captures what the learning process produces (prototypes & parts, process innovations, …etc.). Together, the boxes show how practical tools and real-world rules guide students from digital designs to physical results.

Additive Manufacturing (3D Printing) has revolutionized the way we conceive, prototype, and produce objects, breaking away from traditional subtractive processes by building components layer by layer. This innovative approach aligns closely with broader developments in Industrial and Manufacturing Technologies, offering unprecedented design freedom and rapid iteration cycles. It plays a critical role in accelerating product development and creating complex geometries that were previously difficult or impossible to fabricate.

The synergy between additive processes and Advanced Materials and Manufacturing Technologies allows engineers to explore high-performance composites, metals, and polymers tailored for aerospace, biomedical, and automotive sectors. This capability is further amplified by the integration of Computer-Integrated Manufacturing (CIM) systems and Digital Twin Technology, enabling digital workflows that simulate, monitor, and optimize the manufacturing process in real time.

As sustainability becomes central to industrial strategy, additive techniques contribute to Energy and Resource Efficiency in Manufacturing. By minimizing waste, reducing the need for tooling, and enabling local production, 3D printing aligns with the goals of Sustainable Manufacturing. Additionally, its flexibility supports leaner operations, complementing methods taught under Lean Manufacturing.

A successful 3D printing implementation depends on quality assurance and human-centered design. Topics such as Manufacturing Quality Control and Assurance ensure part reliability, while Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing play a role in optimizing interfaces, equipment usage, and operator comfort. 3D printing is also closely linked to modern frameworks such as Smart Manufacturing and Industry 4.0, where connectivity and automation redefine industrial possibilities.

Beyond prototyping, additive manufacturing reshapes how supply chains function. Its decentralized nature integrates with Supply Chain Management, allowing on-demand production and reduced inventory. It also supports customized fabrication in sectors like Biomechanical Engineering, where prosthetics and implants are tailored to individual anatomical needs.

The growing relevance of 3D printing within Mechanical Engineering is reflected in diverse applications. From lightweight parts in Automotive Engineering to personalized instruments in Robotics and Automation in Mech Eng, additive manufacturing enhances mechanical functionality. Mastery of supporting concepts like Solid Mechanics, Fluid Mechanics and Hydraulics, and Thermodynamics and Heat Transfer is crucial for understanding part performance in real-world conditions.

Design flexibility is a hallmark of additive manufacturing. Coupled with Mechanical Design and Computer-Aided Design (CAD), it allows engineers to create organic, topology-optimized shapes unconstrained by machining limitations. These developments also depend on emerging materials, which are increasingly influenced by Nanotechnology and Advanced Materials in Mech Eng.

3D printing’s integration with Manufacturing and Production Engineering and Control Systems in Mech Engineering demonstrates how modern manufacturing is evolving into a flexible, digitally enabled ecosystem. As additive technologies continue to mature, they redefine not just how we make things—but how we think about engineering, sustainability, and creativity.

- Industrial & Manufacturing Technologies topics:

- Industrial & Manufacturing Technologies – Overview

- Sustainable Manufacturing

- Supply Chain Management

- Smart Manufacturing & Industry 4.0

- Manufacturing Quality Control & Assurance

- Manufacturing Process Design & Optimization

- Lean Manufacturing

- Industrial Automation & Robotics

- Human Factors & Ergonomics in Manufacturing

- Energy & Resource Efficiency in Manufacturing

- Digital Twin Technology

- Computer-Integrated Manufacturing (CIM)

- Advanced Materials & Manufacturing Technologies

- Additive Manufacturing & 3D Printing

Table of Contents

Core Concepts of Additive Manufacturing

The Additive Manufacturing Process

- Digital Design:

- At the heart of additive manufacturing (AM) lies the digital design process, where engineers and designers create a 3D model using Computer-Aided Design (CAD) software. This virtual prototype serves as the blueprint for the final object, allowing for precise control over geometry, dimensions, and functional features.

- Once the model is finalized, it is exported into a printable format such as STL (Standard Tessellation Language) or OBJ, which breaks the complex geometry into a mesh of triangles that can be interpreted by the printer software. This step is critical, as the accuracy of the digital representation directly influences the quality of the final printed part.

- Slicing:

- Slicing software transforms the 3D model into a series of horizontal layers, often as thin as microns, generating a toolpath that the printer follows. Each layer represents a cross-sectional slice of the final object, and the instructions include print speed, temperature, material deposition rate, and movement coordinates.

- This step also allows for the inclusion of support structures, particularly for overhanging features, which are essential in preventing deformation during printing. The sliced file ensures consistent material flow and structural integrity during layer-by-layer construction.

- Material Deposition:

- The core phase of AM involves depositing material, typically in liquid, powder, or filament form, layer by layer according to the defined toolpath. This additive approach stands in contrast to subtractive manufacturing, where material is removed from a solid block.

- Depending on the technology, materials may be extruded, cured with lasers or UV light, or sintered with heat or energy beams. The sequential nature of layer buildup allows for highly complex geometries, including internal channels and lattice structures, that would be difficult or impossible to produce using traditional methods.

- Post-Processing:

- After printing, post-processing steps refine the object’s appearance, mechanical properties, and functionality. These steps may include removing support structures, washing off residual powders or resins, sanding for smoother surfaces, and thermal treatments to enhance strength.

- Post-processing is particularly important in industries such as aerospace and medical, where surface finish and material integrity are critical. In some cases, additional machining or coating is applied to meet precise engineering standards.

Additive Manufacturing Technologies

- Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM):

- FDM is one of the most accessible and widely used 3D printing technologies. It works by extruding a thermoplastic filament through a heated nozzle, which deposits material in layers to form the final part.

- Commonly used materials include PLA (polylactic acid), ABS (acrylonitrile butadiene styrene), and PETG (polyethylene terephthalate glycol). FDM is particularly useful for rapid prototyping, educational use, and low-volume production.

- Stereolithography (SLA):

- SLA uses an ultraviolet laser to selectively cure a photopolymer resin, building the part layer by layer from a vat of liquid material. This method is renowned for its high resolution and smooth surface finish, making it ideal for applications requiring fine detail.

- It is extensively used in industries such as dentistry, jewelry design, and engineering, where precision is crucial. Despite its detail, SLA-printed parts may require post-curing and handling precautions due to material brittleness.

- Selective Laser Sintering (SLS):

- SLS fuses powdered materials—typically nylon or polymers—using a high-powered laser. As each layer is sintered, fresh powder is spread over the surface, allowing continuous building without the need for support structures.

- SLS is ideal for producing functional prototypes, complex geometries, and short-run production parts. The process is highly valued in automotive and aerospace sectors for producing components with good mechanical strength and thermal resistance.

- Direct Metal Laser Sintering (DMLS) / Selective Laser Melting (SLM):

- These technologies melt or sinter metal powders using high-energy lasers to produce dense, high-strength components. Materials such as titanium, aluminum, and stainless steel are commonly used due to their performance characteristics.

- Applications range from turbine blades and heat exchangers in aerospace to customized orthopedic implants in healthcare. According to GE Additive, metal 3D printing has enabled unprecedented design freedom and material efficiency in industrial manufacturing.

- Binder Jetting:

- This process uses a liquid binding agent to selectively bind layers of powdered material. The unbound powder acts as support, allowing intricate designs to be printed without added structures.

- Binder jetting is often used for producing sand molds in casting or for metal parts that are later sintered. It’s appreciated for its speed and scalability in producing large batches of components.

- Electron Beam Melting (EBM):

- EBM uses a focused beam of electrons to melt metal powders in a high-vacuum environment. This results in fully dense parts suitable for high-performance applications, particularly in aerospace and biomedical sectors.

- Materials like titanium and cobalt-chrome are commonly used, and the process is praised for reducing residual stress in the final parts.

- Material Jetting:

- This technique deposits droplets of photopolymer material layer by layer, which are then cured using UV light. It allows for the use of multiple materials and colors in a single build, making it ideal for realistic prototypes and models.

- Material jetting is popular in design visualization, education, and industries requiring visual prototypes with high fidelity.

- Multi Jet Fusion (MJF):

- Developed by HP, MJF uses a fusing agent and detailing agent combined with thermal energy to bind powdered material into functional parts. It offers high strength, fine detail, and fast print speeds.

- MJF is increasingly being used for end-use parts, fixtures, and tooling in industrial applications due to its robust mechanical properties and cost-effectiveness.

Materials Used in Additive Manufacturing

- Plastics:

- Plastics remain the most common material in additive manufacturing, offering a wide range of properties and ease of use. Thermoplastics like PLA, ABS, and PETG are widely used in FDM, while advanced engineering plastics such as PEEK (polyether ether ketone) and polycarbonate are employed for high-performance needs.

- These materials are chosen based on factors such as flexibility, strength, temperature resistance, and chemical stability.

- Metals:

- Metal additive manufacturing materials include aluminum, titanium, stainless steel, and cobalt-chrome, among others. These are crucial for high-stress and high-temperature applications in sectors like aerospace, automotive, and defense.

- Each metal type offers unique properties—titanium is lightweight and corrosion-resistant, while stainless steel provides strength and durability.

- Composites:

- Composites combine a base material with reinforcements like carbon or glass fiber to enhance strength, stiffness, or thermal performance. These are used in applications requiring lightweight yet strong structures, such as drone parts and sporting equipment.

- Ceramics:

- Ceramic materials are used in AM for their high-temperature resistance, hardness, and chemical stability. Applications include medical implants, aerospace components, and tooling for aggressive environments.

- Biomaterials:

- Used primarily in the medical field, biomaterials such as biocompatible polymers and metals support applications like dental crowns, prosthetics, and bone scaffolds. These materials must meet stringent health and safety regulations while promoting biological integration.

- Concrete and Geopolymers:

- In large-scale applications, additive manufacturing is being used with concrete and geopolymer mixtures to construct homes, infrastructure, and shelters. These processes enable rapid, cost-effective building with less labor and waste.

Applications of Additive Manufacturing

Prototyping

- Rapid Prototyping:

- Additive manufacturing revolutionizes the product development cycle by enabling rapid prototyping, which allows engineers and designers to quickly produce physical models from digital concepts. These models can be tested for design feasibility, user interaction, ergonomics, and mechanical performance, significantly accelerating the iterative development process.

- Applications:

- Consumer electronics prototypes allow companies to evaluate aesthetics, functionality, and assembly before committing to high-cost tooling. For instance, smartphone enclosures and wearable devices can be prototyped with full detail and material approximation.

- Automotive part testing benefits greatly from rapid prototyping, as components such as brackets, vents, housings, and mounts can be evaluated in operational environments without delay. This capability enables faster innovation cycles and more agile design adaptations.

- Functional Prototypes:

- Unlike simple visual models, functional prototypes made through additive manufacturing allow for comprehensive testing of form, fit, and function in real-world conditions. Engineers can assess whether components withstand thermal stress, mechanical loads, or chemical exposure as required by the application.

- These prototypes often use production-grade materials or advanced composites, bridging the gap between concept and final production. This approach is especially valuable in fields such as aerospace, medical devices, and automotive engineering.

Custom Manufacturing

- Mass Customization:

- Additive manufacturing enables scalable customization by eliminating the need for specialized tooling or molds. Products can be tailored to individual preferences or anatomical features while still being manufactured in batches, reducing cost and waste.

- Examples:

- Customized footwear uses 3D scanning and printing to fit individual foot shapes, improving comfort and performance. Eyewear can be produced in bespoke designs that match facial features and style preferences.

- Prosthetics benefit significantly, as each device can be fitted to a patient’s anatomy and functional needs, enhancing mobility and quality of life.

- Low-Volume Production:

- When demand does not justify the high cost of injection molding or CNC setups, additive manufacturing provides a flexible solution for producing limited quantities of complex parts. This is particularly beneficial for startups, medical device developers, and companies needing custom spares or upgrades.

- In sectors such as defense and aviation, where unique components are often required in small quantities, AM delivers both precision and economic viability.

Complex Geometries

- Design Freedom:

- One of the most transformative aspects of additive manufacturing is its ability to fabricate complex geometries that are either impossible or highly inefficient to achieve using traditional methods. Structures such as hollow cores, intricate meshes, or functionally graded materials become feasible and cost-effective.

- Examples:

- Lattice structures for lightweight aerospace components reduce mass without compromising strength or rigidity. These parts are engineered for optimal weight-to-strength ratios and thermal performance.

- Internal channels for cooling systems, such as those in turbine blades or high-performance electronic devices, enhance heat dissipation by allowing customized flow pathways.

Aerospace and Defense

- Lightweight Components:

- Aerospace engineers leverage additive manufacturing to design ultra-lightweight structures that meet stringent performance standards. Components can be topologically optimized for stress distribution, material efficiency, and thermal resilience.

- Applications:

- Engine brackets, fuel nozzles, and structural parts are now 3D-printed from high-performance metals such as titanium and Inconel. These components reduce aircraft weight and fuel consumption while maintaining or enhancing mechanical performance.

- On-Demand Manufacturing:

- In remote or hostile environments, the ability to manufacture parts on demand reduces logistics dependencies and enhances readiness. Military units, for instance, can fabricate replacement parts for vehicles or equipment in the field, minimizing downtime.

- This application also streamlines inventory management and enables decentralized supply chains.

Healthcare and Medical

- Prosthetics and Orthotics:

- Additive manufacturing allows for the creation of custom-fit prosthetic limbs and orthotic devices using scans of patient anatomy. These devices are lighter, more comfortable, and tailored to individual functional needs.

- Medical Implants:

- Patient-specific implants, such as cranial plates or spinal cages, can be printed from biocompatible materials to precisely fit a patient’s anatomy, reducing surgical time and improving outcomes. Dental implants and custom abutments are also widely produced via AM.

- Tissue Engineering:

- Bioprinting uses cells and biomaterials to fabricate structures that support tissue regeneration. Researchers are exploring ways to print entire organs or complex tissues using layer-by-layer deposition of living cells, scaffolds, and growth factors.

- Surgical Planning Models:

- Surgeons use 3D-printed anatomical models derived from CT or MRI scans for pre-operative planning. These models improve understanding of complex pathologies and enhance precision during surgeries.

Automotive

- Tooling and Fixtures:

- Custom jigs, molds, gauges, and fixtures can be printed quickly and at low cost. This improves assembly accuracy and reduces the need for complex machining, streamlining production workflows.

- End-Use Parts:

- Automakers increasingly incorporate 3D-printed parts in finished vehicles. Functional parts like brackets, air vents, dashboard elements, and intake manifolds are tailored for performance and aesthetics, particularly in electric vehicles and luxury brands.

Architecture and Construction

- 3D-Printed Buildings:

- Construction-scale 3D printers extrude concrete, geopolymers, or earth-based composites to build entire structures layer by layer. This method reduces material waste, construction time, and labor costs.

- Applications:

- Affordable housing and disaster relief shelters benefit from this innovation, offering rapid deployment and structural integrity in challenging environments. As seen in [ICON’s 3D printed communities](https://www.iconbuild.com/projects), printed homes can now meet building codes and design standards.

- Scale Models:

- Architectural firms use 3D printing to produce detailed scale models that showcase design concepts to clients and stakeholders. These models can include intricate features, landscaping, and interior layouts, offering immersive visualization for planning approvals and marketing.

Energy and Power

- Wind Turbine Components:

- AM enables the production of lightweight and aerodynamically optimized parts for wind turbines, such as nacelle components and sensor housings. This contributes to improved energy capture and easier transportation of modular parts.

- Turbine Blades:

- In gas turbines, 3D printing allows for the inclusion of intricate internal cooling channels that were previously impossible with casting or machining. This results in more efficient thermal management and longer lifespan of turbine components.

Consumer Goods

- Personalized Products:

- AM empowers consumers to co-create personalized jewelry, fashion accessories, smartphone cases, and even custom kitchenware. By combining digital design platforms with 3D printing services, mass personalization becomes accessible and affordable.

- Fast Iterations:

- Consumer brands use AM for quick iterations of new product lines. Designers can test multiple variations in texture, size, and ergonomics within days, accelerating product launches and improving alignment with consumer preferences.

Emerging Trends in Additive Manufacturing

Hybrid Manufacturing

- Hybrid manufacturing integrates the strengths of both additive and subtractive processes, allowing manufacturers to leverage the design freedom of 3D printing while achieving high precision and excellent surface finishes through traditional machining. This combination bridges the gap between prototyping and production-quality parts, expanding the applicability of additive methods to industries with tight tolerance requirements.

- Example: Components such as aerospace brackets or turbine housings may be 3D-printed in rough shape to take advantage of complex geometry and lightweight structures. After printing, CNC machining is used to refine key surfaces, holes, and threads, ensuring dimensional accuracy and material performance in critical areas.

Multi-Material Printing

- Multi-material printing represents a breakthrough in functional prototyping and end-use manufacturing. By enabling the simultaneous use of different materials—such as rigid plastics, elastomers, and conductive inks—this technology allows for the creation of complex assemblies with varying mechanical, thermal, and electrical properties in a single build.

- Applications include producing objects with built-in gaskets, embedded circuits, or movable joints. In biomedical fields, it enables printing anatomical models with tissue-like gradients or prosthetics with rigid frames and soft contact points tailored to patient needs.

Sustainability and Recycling

- Recycled Materials:

- Sustainability has become a driving force behind innovation in additive manufacturing. Increasingly, recycled plastics, such as PET from water bottles or failed 3D prints, are being reprocessed into filament or powder feedstock. This reduces reliance on virgin materials and supports a circular economy model.

- Some companies are developing closed-loop systems where material waste from one process becomes the input for the next. In education and maker spaces, recycling initiatives promote environmental responsibility and cost savings.

- Localized Manufacturing:

- Localized production through 3D printing dramatically lowers the carbon footprint associated with transportation and warehousing. By printing parts on-site or on-demand near the point of use, manufacturers reduce lead times, eliminate overproduction, and tailor outputs to immediate needs.

- This decentralized approach is particularly beneficial in humanitarian aid and remote engineering projects. For instance, 3D-printed medical supplies and repair parts are produced in the field using compact, solar-powered printers, as showcased in [UNICEF’s field innovations](https://www.unicef.org/innovation/stories/3d-printing-field). This empowers communities to meet their own needs sustainably and efficiently.

High-Speed Printing

- Traditionally seen as slower than conventional manufacturing, additive manufacturing is experiencing a leap forward in speed thanks to innovations in hardware and process design. New printer architectures use continuous deposition, parallel nozzle arrays, or advanced light-curing systems to slash print times by up to 90%.

- For example, techniques like Continuous Liquid Interface Production (CLIP) and High-Speed Sintering (HSS) enable faster production of large batches, making 3D printing more competitive for serial manufacturing. These advancements reduce turnaround time and make just-in-time manufacturing a realistic option.

AI and Machine Learning

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) are playing an increasingly vital role in design optimization, process control, and quality assurance in additive manufacturing. AI algorithms can analyze geometric constraints and suggest designs that reduce weight while maintaining or improving structural integrity.

- Generative design software powered by ML explores thousands of iterations and refines designs based on performance goals. In-process monitoring systems use AI to detect defects such as warping or under-extrusion in real-time, triggering corrective actions or halting the print to avoid material waste. These technologies enhance reliability, reduce errors, and accelerate product development cycles.

Automation in 3D Printing

- As additive manufacturing moves toward factory-scale deployment, automation is essential to ensure consistency and throughput. Robotic arms and conveyor systems are being integrated to automate pre-print setup, material replenishment, part removal, and post-processing. This reduces labor costs and enables 24/7 operation with minimal human intervention.

- Automated build platforms can cycle between printing and curing stations, while software tools schedule and manage workflows across multiple printers. In smart factories, entire additive production lines are coordinated using Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) platforms, enabling real-time performance tracking and predictive maintenance. These developments make additive manufacturing scalable and viable for high-volume production in automotive, aerospace, and consumer goods industries.

Benefits of Additive Manufacturing

- Design Flexibility:

- Additive manufacturing revolutionizes product design by enabling the creation of geometries that are impossible or prohibitively expensive to achieve with traditional subtractive methods. Engineers can implement internal lattices, complex curves, hollow structures, and topology-optimized components to enhance performance while reducing material usage.

This design freedom supports innovation in industries like aerospace, where weight reduction and structural integrity are critical. For instance, aerospace brackets with organic, bone-like geometries offer superior strength-to-weight ratios. In architecture and fashion, additive techniques unlock artistic expression with intricate patterns and fluid forms, unconstrained by mold limitations.

- Additive manufacturing revolutionizes product design by enabling the creation of geometries that are impossible or prohibitively expensive to achieve with traditional subtractive methods. Engineers can implement internal lattices, complex curves, hollow structures, and topology-optimized components to enhance performance while reducing material usage.

- Reduced Waste:

- Unlike subtractive manufacturing, which removes material from a solid block (often discarding up to 90% of it), additive manufacturing builds components layer by layer using only the necessary material. This inherently waste-minimizing process is not only environmentally sustainable but also economically advantageous when working with costly resources like titanium or engineering polymers.

Powder-based processes such as Selective Laser Sintering (SLS) and Direct Metal Laser Sintering (DMLS) often allow for the reuse of unused material, further reducing waste and improving sustainability metrics. Additive manufacturing aligns with the principles of lean manufacturing and the circular economy, contributing to greener industrial practices.

- Unlike subtractive manufacturing, which removes material from a solid block (often discarding up to 90% of it), additive manufacturing builds components layer by layer using only the necessary material. This inherently waste-minimizing process is not only environmentally sustainable but also economically advantageous when working with costly resources like titanium or engineering polymers.

- Customization:

- One of the hallmark benefits of additive manufacturing is the ability to produce one-of-a-kind or highly tailored parts without significant changes in tooling or process setup. This is especially beneficial in healthcare, where personalized prosthetics, orthotics, and implants are designed to match a patient’s exact anatomy.

In the consumer market, personalized products—from custom-fit earbuds to fashion accessories—can be printed on demand, enhancing user experience and brand differentiation. Additive technologies empower mass customization, allowing manufacturers to meet specific customer preferences at scale, transforming how products are conceived and delivered.

- One of the hallmark benefits of additive manufacturing is the ability to produce one-of-a-kind or highly tailored parts without significant changes in tooling or process setup. This is especially beneficial in healthcare, where personalized prosthetics, orthotics, and implants are designed to match a patient’s exact anatomy.

- Shorter Lead Times:

- Traditional manufacturing processes involve extensive lead times due to mold production, tooling, and setup adjustments. Additive manufacturing bypasses these steps, enabling the rapid production of prototypes, tooling components, and even end-use parts within hours or days. This accelerates product development cycles and reduces time-to-market—a crucial advantage in competitive industries.

For example, in automotive design, engineers can iterate multiple versions of a component overnight and test them the next day. During crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic, 3D printing was instrumental in rapidly producing medical devices and PPE, highlighting its agility in time-sensitive scenarios. As noted by [MIT Technology Review](https://www.technologyreview.com/2021/01/15/1016313/3d-printing-pandemic-covid-19-response/), this capability is transforming emergency response and supply chain resilience.

- Traditional manufacturing processes involve extensive lead times due to mold production, tooling, and setup adjustments. Additive manufacturing bypasses these steps, enabling the rapid production of prototypes, tooling components, and even end-use parts within hours or days. This accelerates product development cycles and reduces time-to-market—a crucial advantage in competitive industries.

- Cost Efficiency:

- While the cost per unit for additive manufacturing may be higher than traditional methods in mass production, it becomes significantly more cost-effective in low-volume or high-complexity scenarios. It eliminates the need for expensive molds, dies, and jigs, reducing capital investment and setup time.

This cost efficiency makes it ideal for startups, R&D labs, and custom manufacturers where flexibility is more valuable than scale. Furthermore, the consolidation of parts into a single print reduces assembly time and labor costs. In aerospace and defense, where traditional supply chains can be slow and costly, on-demand additive manufacturing offers a leaner and more adaptive alternative.

- While the cost per unit for additive manufacturing may be higher than traditional methods in mass production, it becomes significantly more cost-effective in low-volume or high-complexity scenarios. It eliminates the need for expensive molds, dies, and jigs, reducing capital investment and setup time.

Challenges in Additive Manufacturing

- Material Limitations:

- One of the foremost limitations in additive manufacturing lies in the restricted variety of printable materials. While traditional manufacturing supports a vast array of metals, polymers, ceramics, and composites with well-understood mechanical properties, AM is still developing equivalent options with consistent performance. Not all metals or plastics are currently suitable for layer-by-layer deposition, and even when available, some materials may not exhibit the same strength, ductility, or heat resistance as their conventionally manufactured counterparts.

Moreover, certain high-performance materials require specific environmental conditions, such as inert atmospheres or high temperatures, which demand specialized (and costly) equipment. Research is ongoing to broaden the spectrum of usable feedstocks, including the development of multi-material capabilities and printable biodegradable composites.

- One of the foremost limitations in additive manufacturing lies in the restricted variety of printable materials. While traditional manufacturing supports a vast array of metals, polymers, ceramics, and composites with well-understood mechanical properties, AM is still developing equivalent options with consistent performance. Not all metals or plastics are currently suitable for layer-by-layer deposition, and even when available, some materials may not exhibit the same strength, ductility, or heat resistance as their conventionally manufactured counterparts.

- Surface Finish:

- Parts created using additive manufacturing often exhibit rough or layered surface textures due to the nature of deposition-based fabrication. This can be problematic for applications requiring tight tolerances, smooth finishes, or aesthetic appeal. Components used in aerospace, automotive, and biomedical industries may need additional machining, polishing, or coating to meet specifications.

The need for post-processing not only increases production time and cost but also introduces variability, particularly if the finishing process is manual. Surface anomalies such as stair-stepping, residual powder, or microvoids may also affect fatigue life or corrosion resistance. Advances in hybrid manufacturing—combining AM with CNC finishing—are helping to address this issue, but it remains a barrier to direct use in many critical applications.

- Parts created using additive manufacturing often exhibit rough or layered surface textures due to the nature of deposition-based fabrication. This can be problematic for applications requiring tight tolerances, smooth finishes, or aesthetic appeal. Components used in aerospace, automotive, and biomedical industries may need additional machining, polishing, or coating to meet specifications.

- High Initial Costs:

- Despite the potential for long-term savings in tooling and material usage, the upfront investment in additive manufacturing can be steep. Industrial-grade 3D printers, particularly those capable of processing metals or advanced polymers, often cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. Additionally, these systems require specialized infrastructure, including ventilation, power regulation, and environmental controls.

Beyond hardware, expenses related to software, training, maintenance, and material procurement can be substantial. This high cost of entry can deter startups, small businesses, or educational institutions from adopting AM technologies. As noted by [Forbes](https://www.forbes.com/sites/tjmccue/2021/04/27/the-business-case-for-3d-printing-why-additive-manufacturing-is-growing/), strategic investments and innovation in open-source and desktop solutions are helping democratize access, but cost remains a significant hurdle.

- Despite the potential for long-term savings in tooling and material usage, the upfront investment in additive manufacturing can be steep. Industrial-grade 3D printers, particularly those capable of processing metals or advanced polymers, often cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. Additionally, these systems require specialized infrastructure, including ventilation, power regulation, and environmental controls.

- Size Constraints:

- The dimensions of 3D printed parts are inherently limited by the build volume of the printer. While small desktop printers may produce parts under 30 cm in any direction, even high-end industrial systems are constrained by chamber size. This poses challenges for sectors like aerospace, construction, and energy where large components are common.

Solutions such as modular printing (assembling parts after printing), gantry-style machines, and mobile concrete 3D printers are being developed, but they often introduce structural weak points or increase production complexity. For now, large-scale additive manufacturing remains a specialized area with limited accessibility.

- The dimensions of 3D printed parts are inherently limited by the build volume of the printer. While small desktop printers may produce parts under 30 cm in any direction, even high-end industrial systems are constrained by chamber size. This poses challenges for sectors like aerospace, construction, and energy where large components are common.

- Regulatory Hurdles:

- Gaining certification and meeting compliance standards is a major barrier for AM-produced parts, especially in tightly regulated fields such as aerospace, medical devices, and defense. Regulatory agencies require robust data on material properties, repeatability, reliability, and long-term performance—criteria that are still evolving in the AM space.

The lack of standardized processes and quality control frameworks across different printers and materials further complicates regulatory approval. Efforts by organizations like ASTM International and ISO are working toward harmonized guidelines, but until universally accepted standards are established, manufacturers must navigate a complex and often time-consuming certification process. This limits the widespread adoption of AM in safety-critical applications despite its technical potential.

- Gaining certification and meeting compliance standards is a major barrier for AM-produced parts, especially in tightly regulated fields such as aerospace, medical devices, and defense. Regulatory agencies require robust data on material properties, repeatability, reliability, and long-term performance—criteria that are still evolving in the AM space.

Future Directions in Additive Manufacturing

- Mass Adoption in Industries:

- Additive manufacturing is steadily moving beyond the prototyping phase into full-scale industrial production. With growing confidence in the reliability and repeatability of AM processes, industries such as automotive, aerospace, healthcare, and consumer goods are embracing the technology for producing end-use parts, custom components, and production tooling. Factors driving this mass adoption include reduced lead times, supply chain flexibility, and enhanced design possibilities.

Furthermore, the development of more robust design for additive manufacturing (DfAM) guidelines and greater collaboration between hardware manufacturers and software developers is enabling seamless integration of AM into traditional manufacturing workflows. In the near future, we can expect hybrid facilities that combine additive and subtractive systems operating in smart factories, achieving optimal cost-efficiency and responsiveness.

- Additive manufacturing is steadily moving beyond the prototyping phase into full-scale industrial production. With growing confidence in the reliability and repeatability of AM processes, industries such as automotive, aerospace, healthcare, and consumer goods are embracing the technology for producing end-use parts, custom components, and production tooling. Factors driving this mass adoption include reduced lead times, supply chain flexibility, and enhanced design possibilities.

- Distributed Manufacturing:

- Distributed manufacturing represents a paradigm shift from centralized production facilities to decentralized networks of localized, on-demand fabrication units. Powered by digital design files and standardized printing protocols, this model allows manufacturers to produce parts closer to the point of use, significantly reducing shipping costs and environmental impact.

In disaster zones, military operations, and remote communities, distributed AM can be a game-changer. A digital file sent from a design center can be printed in real time by local hubs using regionally available materials. This approach also enhances resiliency during supply chain disruptions, as observed during the COVID-19 pandemic when 3D printing was used to locally produce critical medical components like face shields and ventilator parts. The [World Economic Forum](https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/01/3d-printing-supply-chains-pandemic) has emphasized the role of 3D printing in building resilient supply chains through distributed manufacturing.

- Distributed manufacturing represents a paradigm shift from centralized production facilities to decentralized networks of localized, on-demand fabrication units. Powered by digital design files and standardized printing protocols, this model allows manufacturers to produce parts closer to the point of use, significantly reducing shipping costs and environmental impact.

- Advancements in Bioprinting:

- Bioprinting is emerging as one of the most transformative subfields of additive manufacturing. Researchers are now able to print biological materials—including cells, hydrogels, and biomaterials—into complex three-dimensional structures that mimic natural tissue architecture. While fully functional organ printing remains a long-term goal, major milestones have been achieved in creating lab-grown skin, cartilage, and vascular structures.

The use of patient-derived cells and customized scaffold designs allows for personalized medicine and regenerative therapies. Bioprinted tissues are also accelerating pharmaceutical testing by enabling drug evaluations on tissue models without human trials. As stem cell research, tissue engineering, and AM technologies converge, bioprinting could revolutionize healthcare, organ transplantation, and biomedical research.

- Bioprinting is emerging as one of the most transformative subfields of additive manufacturing. Researchers are now able to print biological materials—including cells, hydrogels, and biomaterials—into complex three-dimensional structures that mimic natural tissue architecture. While fully functional organ printing remains a long-term goal, major milestones have been achieved in creating lab-grown skin, cartilage, and vascular structures.

- Large-Scale Printing:

- The scale of additive manufacturing is no longer confined to small and medium-sized components. Advances in robotic arms, gantry systems, and concrete-based extrusion are enabling the creation of large-scale structures such as homes, bridges, and aircraft parts. Large-format printers can now build full-sized architectural elements and infrastructure components layer by layer, making AM relevant for the construction and civil engineering sectors.

The ability to 3D print directly on-site reduces construction waste, labor costs, and construction time. In some cases, entire buildings have been completed in under 24 hours using this approach. Moreover, large-scale AM supports innovative geometries that are difficult or impossible with traditional methods, such as curvilinear walls, embedded conduits, and adaptive load-bearing forms.

- The scale of additive manufacturing is no longer confined to small and medium-sized components. Advances in robotic arms, gantry systems, and concrete-based extrusion are enabling the creation of large-scale structures such as homes, bridges, and aircraft parts. Large-format printers can now build full-sized architectural elements and infrastructure components layer by layer, making AM relevant for the construction and civil engineering sectors.

- Space Applications:

- Space agencies such as NASA and ESA are exploring the use of additive manufacturing for extraterrestrial missions. 3D printing tools, replacement parts, and structural elements on-site in space or on planetary surfaces can drastically reduce mission payloads and costs. This “in-situ resource utilization” (ISRU) strategy involves using local materials such as lunar regolith or Martian soil for printing habitats, landing pads, and radiation shields.

In microgravity environments, printers designed to operate without Earth’s gravity are being tested aboard the International Space Station (ISS). These systems allow astronauts to fabricate items on-demand, improving self-sufficiency during long-duration missions. As humanity ventures further into space, additive manufacturing will be pivotal for sustaining life and building infrastructure beyond Earth.

- Space agencies such as NASA and ESA are exploring the use of additive manufacturing for extraterrestrial missions. 3D printing tools, replacement parts, and structural elements on-site in space or on planetary surfaces can drastically reduce mission payloads and costs. This “in-situ resource utilization” (ISRU) strategy involves using local materials such as lunar regolith or Martian soil for printing habitats, landing pads, and radiation shields.

Why Study Additive Manufacturing (3D Printing)

Revolutionizing the Manufacturing Landscape

Additive manufacturing builds objects layer by layer from digital models. Students learn how this technique reduces material waste and enables rapid prototyping. It offers new possibilities in design and fabrication.

Materials and Printing Processes

The course introduces materials like thermoplastics, resins, and metals. Students study printing technologies such as FDM, SLA, and SLS. Understanding these processes enables them to choose the right method for each application.

Design for Additive Manufacturing (DfAM)

Additive manufacturing requires a different approach to design. Students learn to create complex geometries, lightweight structures, and customized parts. This supports innovation in engineering and product development.

Applications Across Disciplines

3D printing is used in healthcare, aerospace, automotive, and education. Students explore its role in producing implants, drones, tools, and teaching aids. This multidisciplinary nature opens a wide range of career opportunities.

Future Trends and Industry Disruption

Students explore how additive manufacturing is transforming supply chains and enabling local production. They study its impact on sustainability, speed-to-market, and customization. This prepares them to lead in a rapidly evolving industry.

Additive Manufacturing: Conclusion

Additive manufacturing (AM), also known as 3D printing, stands at the forefront of a technological revolution that is fundamentally transforming how products are conceptualized, developed, and brought to market. Unlike traditional subtractive manufacturing, which involves removing material to shape objects, AM builds components layer by layer, enabling unprecedented freedom in form and structure. This paradigm shift empowers designers and engineers to transcend the constraints of conventional machining, allowing the creation of intricate geometries, internal cavities, and lattice frameworks that enhance both functionality and material efficiency.

The advantages of AM extend far beyond the design phase. Industries such as aerospace and automotive have embraced AM for its ability to produce lightweight components that maintain structural integrity while improving fuel efficiency and performance. In the medical sector, AM has unlocked a new era of personalized care, enabling the production of patient-specific implants, dental appliances, and surgical guides that improve outcomes and reduce recovery times. Likewise, in construction and architecture, large-scale 3D printers are redefining building practices by facilitating the rapid construction of complex, sustainable structures at reduced costs.

As additive manufacturing continues to evolve, it is increasingly seen not just as a prototyping tool but as a viable method for full-scale production. Developments in high-speed printing, multi-material capabilities, and process automation are paving the way for AM to become integrated into digital, smart factories. The technology’s potential for mass customization allows manufacturers to cater to individual customer needs without the inefficiencies of retooling or large inventories. At the same time, AM promotes localized, on-demand production that can dramatically shorten supply chains, reduce transportation emissions, and enhance manufacturing agility.

Importantly, the sustainability potential of AM cannot be overstated. By using only the necessary amount of material, it minimizes waste while enabling the use of recycled inputs and biodegradable substances. Organizations around the world, including the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, are researching how AM technologies can contribute to circular economies by supporting closed-loop material cycles and decentralized production systems. These efforts align with broader goals of reducing environmental footprints and promoting ethical manufacturing practices.

Looking ahead, the trajectory of additive manufacturing points toward even greater innovation. The convergence of AM with artificial intelligence, machine learning, digital twins, and blockchain will redefine the boundaries of industrial production. From printing organs and habitats in space to developing hyper-efficient turbines and bespoke consumer products, the possibilities are virtually limitless. As educational institutions, governments, and industries invest in skill development and research, the adoption of AM will accelerate, transforming supply chains and reshaping the global economy.

In summary, additive manufacturing is no longer a niche technology—it is a transformative force reshaping how we design, build, and think about manufacturing. Its blend of flexibility, efficiency, customization, and sustainability positions it as a central pillar of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. As we move into a future defined by rapid innovation and urgent environmental challenges, AM will play an indispensable role in driving progress, empowering industries, and building a more responsive and sustainable world.

Additive Manufacturing and 3D Printing: Frequently Asked Questions

This FAQ highlights core questions students often ask about additive manufacturing and 3D printing, from basic concepts to applications, challenges and economic impact.

1. What is additive manufacturing, and how does it differ from traditional subtractive manufacturing methods?

Additive manufacturing is a family of technologies that build three-dimensional parts by adding material layer by layer from a digital model, whereas traditional subtractive methods start from a solid block and remove material by cutting, drilling or milling to reach the final shape. In additive processes, material is deposited only where it is needed, enabling complex internal geometries, lightweight lattices and customised designs with relatively little waste. Subtractive processes generally offer excellent dimensional accuracy, surface finish and speed for high-volume production, but they generate more scrap and are less suited to highly intricate or highly customised parts.

2. What are the most common types of additive manufacturing technologies, and what materials do they typically use?

Common additive manufacturing technologies include Fused Deposition Modelling, which extrudes thermoplastic filaments such as PLA, ABS and PETG; Stereolithography and Digital Light Processing, which cure liquid photopolymer resins using light; Selective Laser Sintering for powdered polymers like nylon and other engineering plastics; and powder bed fusion methods such as Direct Metal Laser Sintering, Selective Laser Melting and Electron Beam Melting for metal powders including stainless steels, aluminium and titanium alloys. Each process is optimised around specific material forms and properties, so the choice of technology and the choice of material are closely linked. As a result, designers must match mechanical, thermal and surface requirements of the part with a compatible process-material combination.

3. What are the primary advantages of using 3D printing in industrial manufacturing?

In industrial settings, 3D printing offers major advantages in design freedom, customisation, material efficiency and development speed. It allows engineers to create complex integrated geometries, consolidate multi-part assemblies into single printed components and tailor shapes for weight reduction or performance without new tooling. At the same time, it is highly attractive for rapid prototyping and low-volume or bridge production because parts can be made directly from digital files, shortening time-to-market, reducing inventory and tooling costs and supporting on-demand, localised manufacturing of spare parts or specialised components.

4. What are the key challenges associated with additive manufacturing in industrial applications?

Key challenges in industrial additive manufacturing include limited material portfolios, slower build rates compared to traditional mass production processes, and the need for extensive post-processing to achieve required surface finishes and tolerances. High capital costs for advanced metal and polymer systems, variation in part quality between machines, and evolving standards for qualification and certification also complicate adoption. In addition, issues of design data protection, workforce skills and integration of additive processes into existing production lines and supply chains must be addressed for widespread, economically viable use.

5. How do different 3D printing materials affect the properties and applications of the final printed products?

The choice of 3D printing material strongly determines the mechanical, thermal, chemical and aesthetic properties of printed parts and thus the applications they can serve. Commodity thermoplastics are widely used for concept models and low-load functional parts, engineering polymers and fibre-reinforced composites enable robust, lightweight components, and metal alloys provide high strength and temperature resistance for demanding aerospace, automotive and tooling uses. Resins, ceramics and biomaterials extend additive manufacturing into areas such as dental and medical devices, high-temperature components and bioengineered structures, so selecting an appropriate material is as important as choosing the printing process itself.

6. What are the environmental impacts of additive manufacturing compared to traditional manufacturing methods?

Compared with conventional subtractive methods, additive manufacturing can reduce environmental impact by using less raw material, enabling lightweight designs that save energy in use and supporting on-demand, local production that cuts inventory and transport requirements. However, some additive processes, particularly metal powder bed fusion, are energy intensive and may rely on materials or post-processing steps that are difficult to recycle or that emit pollutants. The overall footprint therefore depends on the full product life cycle, including energy sources, material choices, process efficiency and end-of-life strategies, and careful assessment is needed before claiming environmental benefits in specific cases.

7. How can additive manufacturing be integrated with traditional manufacturing processes to create hybrid manufacturing systems?

Hybrid manufacturing systems integrate additive processes with conventional machining and forming so that each method is used where it is strongest. A common approach is to build a near-net-shape part additively and then finish critical surfaces with CNC machining to achieve tight tolerances and good surface quality, sometimes within a single multi-process machine tool. Such systems allow complex internal features, weight saving structures and design customisation from the additive stage to be combined with the precision, productivity and familiarity of traditional processes, improving efficiency, part performance and design possibilities compared with using either approach alone.

8. What are the key factors that determine the selection of a 3D printing technology for a specific industrial application?

Selecting a 3D printing technology for an industrial application involves balancing material requirements, part geometry, build volume, surface finish and tolerance needs, production speed, cost constraints and post-processing demands. Engineers consider whether the process supports the required polymer, metal or composite, whether it can handle the complexity and size of the design, and how many parts must be produced. They also evaluate machine and material costs, the level of geometric detail and accuracy achievable, the effort needed for support removal and finishing, and any sector-specific requirements such as biocompatibility, flame retardancy or aerospace qualification.

9. How does the choice of additive manufacturing technology influence the mechanical properties of the final product?

Different additive manufacturing technologies produce distinct microstructures, densities and levels of anisotropy, so the same nominal material can exhibit very different mechanical properties depending on the process used. Factors such as layer thickness, energy input, scan strategy and cooling rate influence pore content, grain structure and interlayer bonding, which in turn affect strength, stiffness, fatigue resistance and impact behaviour. As a result, designers must take into account build orientation, process parameters and the need for heat treatment or other post-processing when targeting specific mechanical performance in load-bearing applications.

10. What are the potential applications of additive manufacturing in the aerospace industry, and how do they benefit from AM technologies?

In aerospace, additive manufacturing is used for lightweight structural brackets, optimised engine components with internal cooling passages, complex fuel system parts, customised cabin fittings, tooling and fixtures, and on-demand spares. These applications benefit from the ability to reduce component mass without sacrificing strength, consolidate assemblies into single parts, embed advanced cooling or flow features and produce small batches economically. The resulting weight savings, performance gains and supply chain flexibility help improve fuel efficiency, reduce emissions, shorten lead times and support maintenance and upgrade activities throughout an aircrafts life.

11. What are the economic implications of adopting additive manufacturing in industrial sectors, and how can businesses assess the return on investment?

Adopting additive manufacturing affects cost structures by reducing or eliminating tooling, lowering material waste and inventory requirements, and enabling revenue from customised or higher value products, but it also introduces significant capital and operating expenses for equipment, materials and skilled staff. To assess return on investment, businesses compare these costs with savings from shorter development cycles, more efficient production of complex or low-volume parts, supply chain simplification and potential new market opportunities. Tools such as cost-benefit analysis, break-even calculations, productivity and quality metrics, and scenario modelling for different volumes and product mixes help decision makers quantify the financial impact of integrating additive technologies.

12. How does additive manufacturing support innovation and design freedom in product development, and what are some examples of innovative products created using AM?

Additive manufacturing supports innovation by removing many geometric constraints of traditional processes, allowing designers to use topology optimisation, lattice structures, internal channels and organic forms to meet performance targets with less material. It also makes it easier to customise products for individual users and to iterate quickly through prototypes, which accelerates experimentation and learning. Notable examples include 3D printed fuel nozzles and heat exchangers with complex internal paths, patient-specific medical implants, lightweight automotive and aerospace brackets, customised footwear and sports equipment, and artistic or architectural pieces that exploit intricate, previously impractical geometries.

Additive Manufacturing: Review Questions with Detailed Answers

These review questions invite you to think more deeply about how additive manufacturing and 3D printing reshape engineering design, production strategies and industrial practice.

1. What is meant by additive manufacturing, and in what practical ways does it contrast with traditional subtractive manufacturing?

Answer:

Additive manufacturing refers to a family of processes that build three-dimensional parts by placing material only where it is required, generally in thin layers, directly from a digital design file. Instead of carving a shape out of a solid workpiece, as in milling, turning or drilling, the additive process grows the part from nothing, one layer at a time, until the full geometry is formed.

Key contrasts:

- Direction of material flow: Additive processes start from zero material and add up to the final shape, while subtractive ones start from a block and remove material downwards to the final geometry.

- Waste generation: Because additive manufacturing deposits only the required material (plus any supports), scrap is often much lower than in machining operations that generate large volumes of chips.

- Geometric freedom: Complex internal channels, lattice structures and organic contours are far easier to realise additively than with cutting tools that must physically reach every surface.

- Tooling and setup: Additive systems can switch from one part to another simply by loading a new digital file, whereas subtractive processes often depend on dedicated fixtures, jigs and tooling that require time and cost to prepare.

Conclusion: In practice, additive manufacturing is best thought of as a complementary approach to subtractive manufacturing, trading higher geometric freedom and lower waste for different constraints in speed, surface finish and cost structure.

2. Which major categories of additive manufacturing technologies are widely used, and what types of materials are associated with each?

Answer:

Engineers rarely speak of “3D printing” as a single process; instead, they choose from several technology families, each tuned to certain material forms and performance needs.

- Fused Deposition Modelling (FDM): Uses spooled thermoplastic filament such as PLA, ABS, PETG or engineering polymers that is softened and extruded through a heated nozzle, ideal for prototypes and functional plastic parts.

- Stereolithography (SLA) and Digital Light Processing (DLP): Work with liquid photopolymer resins that harden when exposed to ultraviolet light, enabling very fine details and smooth surfaces for models, dental parts and intricate components.

- Selective Laser Sintering (SLS): Fuses layers of polymer powder, commonly nylon and its composites, to produce tough, functional parts with good mechanical properties and no support structures embedded in the part.

- Metal powder bed fusion (DMLS/SLM/EBM): Uses high-energy lasers or electron beams to melt or sinter metal powders such as stainless steels, aluminium and titanium alloys, producing dense, load-bearing components for aerospace, medical and high-end engineering applications.

- Emerging and specialised processes: Techniques such as binder jetting, material jetting and directed energy deposition accommodate ceramics, sand, certain metals and even multi-material builds for niche applications.

Conclusion: Each process–material combination defines a distinct “toolbox”, so understanding both the technology and the compatible materials is essential when selecting a suitable additive route.

3. From an industrial engineering perspective, what are the main reasons companies turn to 3D printing as part of their manufacturing strategy?

Answer:

Industrial firms embrace 3D printing because it changes where and how value is created in the product lifecycle.

- Design agility: Complex internal features, conformal cooling channels and integrated assemblies can be designed for function first, rather than for ease of machining, giving significant performance gains.

- Rapid learning cycles: Prototypes can be printed directly from CAD data, tested, modified and reprinted quickly, compressing the development timeline from months to weeks or even days.

- Economics at low volume: For small batches or customised parts, the absence of dedicated tooling makes additive processes cost-competitive or even superior to traditional routes.

- On-demand and local production: Spare parts and specialised tooling can be produced close to the point of use, reducing storage requirements and shortening supply chains.

- Lightweighting and performance: Topology-optimised, lattice-filled components reduce mass while maintaining or improving strength, crucial in sectors where every gram matters.

Conclusion: The real power of 3D printing is not simply “making parts differently” but enabling new business models, faster innovation and more tailored products.

4. Industrial adoption of additive manufacturing is not straightforward. What practical obstacles do engineers and managers encounter when deploying AM at scale?

Answer:

Despite its promise, additive manufacturing introduces technical, organisational and economic challenges that must be handled carefully.

- Material and process limits: Available materials may not yet match the full property range of wrought or cast alloys, and machine build envelopes can constrain part size.

- Throughput and scalability: Layer-by-layer deposition is inherently time-consuming, so producing large numbers of parts can be slower than established mass production methods.

- Post-processing burden: Support removal, surface finishing, heat treatment and inspection add time and cost, and must be built into process planning.

- Capital and operating costs: High-end systems, especially for metals, are expensive to purchase and maintain, and require trained operators and robust safety practices.

- Quality assurance and certification: Proving consistent material properties and process reliability across machines, batches and sites is demanding, particularly in regulated sectors such as aerospace and medical devices.

- Data and IP concerns: Digital design files can be copied and shared easily, raising questions about intellectual property protection and version control.

Conclusion: Successful industrial use of AM therefore depends as much on sound engineering management, standards and workforce development as it does on the machines themselves.

5. In what ways does the choice of printing material shape the performance and appropriate use of a 3D printed component?

Answer:

The same geometry printed in different materials can behave like very different products, so material selection is central to additive design.

- Mechanical behaviour: Metals and high-performance polymers can carry significant loads, whereas basic thermoplastics or standard resins are better suited to visual models and light-duty parts.

- Surface quality and detail: Photopolymer resins routinely achieve fine features and smooth surfaces, while some filament-based prints retain visible layer lines and may require finishing for cosmetic or sealing purposes.

- Environmental resistance: Nylons, engineering polymers and certain composites resist heat, chemicals and abrasion, making them appropriate for demanding environments where simple PLA would degrade.

- Biological and medical needs: Biocompatible polymers, metals and bioinks enable implants, guides and tissue scaffolds, where safety and interaction with living tissue are critical design constraints.

- Functional properties: Conductive, flexible, translucent or high-temperature materials open up applications in electronics, wearables, optics and thermal management.

Conclusion: To use additive manufacturing effectively, designers must think material-first as well as geometry-first, matching each application to a suitable material-process pair.

6. When comparing additive and traditional manufacturing, how should engineers think about their relative environmental footprints?

Answer:

It is tempting to assume that additive manufacturing is automatically “greener”, but the reality is more nuanced.

- Material efficiency: Additive processes can dramatically cut raw material waste by building only the part and necessary supports, whereas subtractive methods may discard a large fraction of the starting stock as chips.

- Energy use: Some additive systems, especially those using high-powered lasers or electron beams, consume significant electrical energy per part, which may offset material savings if the energy is carbon-intensive.

- Lightweight designs: Parts optimised for reduced mass can improve energy efficiency during the use phase, for example by lowering fuel consumption in vehicles or aircraft.

- Logistics and inventories: On-demand, local printing reduces the need for long-distance transport and large warehouses, cutting associated emissions.

- End-of-life and recyclability: Not all powders, resins or support materials are easy to recycle, and contamination in recycled feedstock can limit reuse.

Conclusion: A fair environmental comparison requires full life-cycle assessment, from material production and energy inputs to product use and disposal, rather than focusing only on the build step.

7. What does a hybrid manufacturing system look like in practice, and how can additive and traditional processes complement one another?

Answer:

Hybrid manufacturing brings additive and subtractive processes into a coordinated workflow, treating them as partners rather than competitors.

- Near-net shape plus finishing: A metal part may be grown additively to incorporate complex internal passages, then transferred (physically or within the same machine) to a CNC stage that accurately finishes critical interfaces and bearing surfaces.

- Feature-level combination: Traditional methods can create simple, high-precision base forms, while additive methods “add on” complex features, repair worn regions or build conformal channels that are impossible to machine internally.

- Multi-process equipment: Hybrid machine tools that integrate a laser deposition head with milling spindles allow parts to be built and cut in a single setup, reducing alignment errors and setup time.

- Supply chain strategy: Organisations can reserve additive manufacturing for high-value, complex or time-critical components, while continuing to use casting, forging and machining for standard parts.

Conclusion: By thoughtfully combining both worlds, hybrid systems can deliver parts that are more capable, produced more efficiently, than either approach used in isolation.

8. When an engineer must choose a 3D printing process for a new industrial part, what practical questions should they ask to guide that decision?

Answer:

Selecting a printing process is a multi-criteria decision rather than a simple technical choice.

- What material properties are required? The needed strength, stiffness, temperature resistance, chemical resistance and regulatory status will narrow the set of feasible processes.

- How complex is the geometry? Very fine features or intricate internal channels may favour resin-based or powder-bed systems over filament-based approaches.

- What part size and build volume are involved? Some machines handle only small components, whereas others are designed for large-format parts or many parts nested together.

- What level of surface finish and tolerance is acceptable? If very smooth surfaces and tight tolerances are critical, the process choice and expected post-processing must reflect that.

- How many parts are needed and how fast? Low-volume or one-off production is a natural fit for many AM processes, while higher volumes may demand faster systems or a hybrid with traditional manufacturing.

- What budget constraints exist? Equipment price, material cost per kilogram and labour for finishing all affect the true cost per part.

Conclusion: Systematic evaluation of these questions ensures that the chosen 3D printing route is technically appropriate and economically sensible for the task at hand.

9. In what ways does the selected additive manufacturing process influence the mechanical performance of a printed part?

Answer:

Mechanical properties in additive manufacturing emerge not just from the base material, but from how the process structures that material in three dimensions.

- Layer bonding and anisotropy: Processes that rely on fusing layers together can produce parts that are stronger in the plane of the layers than through the build direction, leading to directional strength and stiffness.

- Pore content and density: Powder-based processes may leave residual porosity if parameters are not optimised, which can act as crack initiators under cyclic loading.

- Microstructure and residual stress: Rapid thermal cycles can create fine microstructures but also build in residual stresses that, if unmanaged, cause distortion or premature failure; post-build heat treatments are often used to relieve these.

- Surface condition: Rough surfaces not only affect appearance and fit but can also reduce fatigue life, because microscopic notches act as stress concentrators.

Conclusion: When specifying mechanical performance, engineers must treat process parameters, build orientation and post-processing as design variables alongside the choice of material and geometry.

10. Why has the aerospace sector been particularly active in adopting additive manufacturing, and what types of components illustrate this trend?

Answer:

Aerospace companies have strong incentives to reduce weight, improve performance and manage complex supply chains, making them natural early adopters of additive manufacturing.

- Lightweight structural hardware: Topology-optimised brackets, mounts and support structures printed in aluminium or titanium can deliver significant mass savings compared with conventionally machined parts.

- Engine and thermal components: Combustor liners, fuel nozzles and heat exchangers with intricate internal channels can be produced as single pieces, improving efficiency and reducing part counts.

- Cabin and interior fittings: Customised seat frames, ventilation components and aesthetic trim benefit from design freedom and reduced inventory.

- Tooling and support equipment: Lightweight jigs, fixtures and assembly aids can be produced quickly to support manufacturing and maintenance operations.

Conclusion: These applications show how additive manufacturing can simultaneously address performance, weight, cost and logistical challenges in a highly demanding industry.

11. From a business point of view, how should a company think about the economics of adopting additive manufacturing and evaluating its return on investment?

Answer:

The economics of additive manufacturing go beyond the price of a machine; they involve a shift in how products are designed, produced and delivered.

- Cost reductions: Savings may arise from eliminating moulds and dies, cutting material waste, reducing manual assembly steps and lowering inventory levels through on-demand production.

- Value creation: New revenue streams can emerge from customised products, performance-enhanced parts or spare-part services that were not feasible before.

- Time advantages: Faster development and shorter lead times can provide a competitive edge that is hard to quantify purely in unit cost terms.

- Investment and operating costs: Capital expenditure on equipment, facilities and training, as well as ongoing materials, maintenance and software licences, must all be accounted for.

Assessing ROI:

- Compare the full cost per part, including post-processing, with traditional routes at the relevant production volume.

- Estimate financial benefits from reduced time-to-market, lower inventory and improved product performance.

- Use break-even and sensitivity analyses to see how changes in volume, material cost or cycle time affect profitability.

Conclusion: A careful, data-driven ROI assessment helps companies decide where additive manufacturing genuinely adds economic value rather than adopting it simply because it is new.

12. In what concrete ways does additive manufacturing expand design freedom and stimulate innovation, and what kinds of products demonstrate this potential?

Answer:

Additive manufacturing frees designers from many of the geometric constraints that shaped twentieth-century products, and that freedom has tangible consequences.

- Functionally driven shapes: Parts can be shaped to follow load paths, fluid flows or thermal gradients, rather than being constrained by tool access or draft angles.