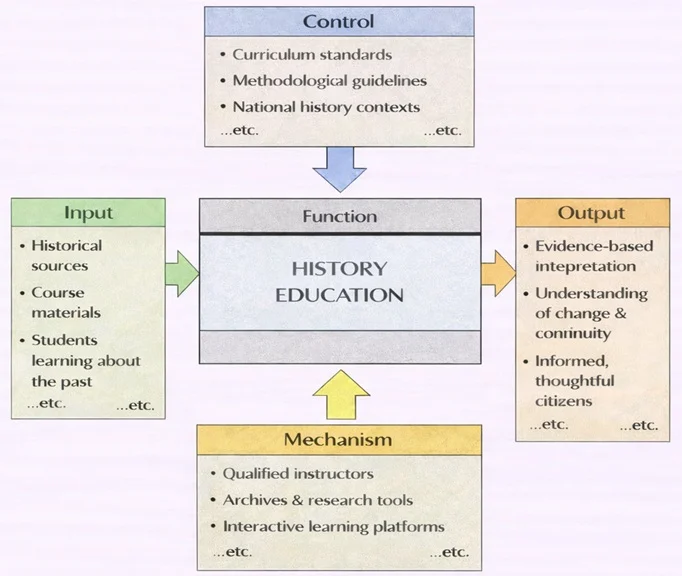

History Education can be understood as a learning function that turns “the past” into a disciplined way of thinking. The main inputs are historical sources (documents, artifacts, records, testimonies), course materials that organize those sources into learning pathways, and students who are learning to ask better questions about what happened and why. The process is guided by controls such as curriculum standards, methodological guidelines, and national history contexts, which shape what topics are emphasized, how evidence should be handled, and how local narratives connect to wider world history. The function is enabled by mechanisms: qualified instructors who model careful reasoning, archives and research tools that make evidence accessible, and interactive learning platforms that support discussion, practice, and feedback. When these elements work together, the outputs are more than memorized dates: students develop evidence-based interpretation, a sharper understanding of change and continuity, and the habits of informed, thoughtful citizens who can evaluate claims about the past with clarity and care.

The study of history is a multifaceted journey into the ideas, events, systems, and personalities that have shaped human society. It extends far beyond timelines and facts, offering critical insights into the structures of power, the evolution of economies, and the development of cultural norms. For instance, exploring the history of ideas reveals how philosophies and ideologies have transformed societies and institutions over time. These ideas are often at the heart of major shifts in political systems and are closely tied to movements that demand reform or revolution.

Understanding political economy through its historical development provides crucial insights into how states balance governance and markets. This is especially relevant in today’s context, where economic history and financial history continue to shape global inequality, trade relations, and fiscal policy. The rise and transformation of economic thought can be traced through the history of economic thought, illuminating how theories evolve in response to crises and innovations.

At the heart of any society’s transformation are its social forces. The history of social movements helps us understand how citizens challenge structures of power, while education history sheds light on how knowledge has been controlled and democratized. These threads are essential for interpreting revolutions, reforms, and institutional change.

Equally vital is the role of diplomacy and war in shaping modern nation-states. Diplomatic history highlights the subtle negotiations and bold initiatives that have influenced peace treaties and global alignments. It is through this lens that figures from diplomatic personalities to architects of economic diplomacy emerge as central to global transformation.

War is often a tragic but pivotal force in history. Through the lens of economic history of warfare and the study of guerrilla warfare and insurgency, students learn how economies mobilize for conflict, and how non-state actors reshape political destinies. The economic consequences of war, in turn, affect everything from public finance to postwar recovery.

Electoral processes and legitimacy are also integral to historical inquiry. The development of electoral history, debates over electoral fraud and integrity, and the design of electoral systems and political parties offer a view into how power is distributed and challenged in democratic and authoritarian contexts alike.

History is not only political or economic; it is also deeply cultural. Fields like gender and cultural history encourage critical reflection on identity, power, and representation, while cultural diplomacy shows how art, language, and tradition serve as tools of influence. Broader analyses of global political thought connect these cultural dimensions to transnational debates.

In more recent decades, the impact of industrialization and consumption on nature has led to growing interest in environmental economic history, which ties together ecological change, economic systems, and policy decisions.

Finally, history remains a dynamic discipline because it is constantly revisited, reinterpreted, and applied to the present. From exploring alliances and institutional collaborations to refining economic theory based on past missteps, the study of history trains students to think critically, connect the dots, and prepare for an uncertain future.

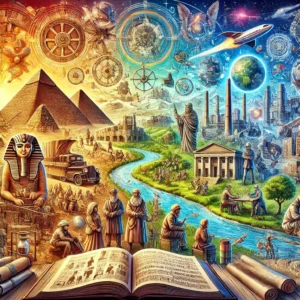

This richly detailed illustration symbolically represents the breadth of the humanities and social sciences across history and cultures. At the center lies an open book, representing accumulated human knowledge. From it flows a river of ideas that connects ancient civilizations (pyramids, temples, classical scholars), cultural expression (art, storytelling, philosophy), social life (communities, dialogue, governance), and the modern world (cities, technology, exploration). Celestial symbols, maps, and instruments in the sky suggest inquiry, reflection, and the pursuit of meaning. The image visually communicates the continuity of human thought across time — a core theme of Prep4Uni.online’s approach to learning.

- Humanities & Social Sciences topics:

- Overview

- Anthropology

- Cultural Studies

- History

- Literature

- Philosophy

- Political Science

- International Relations

- Psychology

- Religious Studies

- Sociology

- Linguistics

Table of Contents

The Scope and Significance of Studying the Past

Understanding Change Over Time

- One of the most profound insights gained from studying earlier periods is the recognition that societies, institutions, and belief systems are not static—they are constantly evolving. Examining how transformations unfold over generations allows learners to grasp the fluid nature of governance, economics, culture, and technology.

- Transitions from one dominant structure to another—such as the gradual shift from feudalism to capitalism in post-medieval Europe—provide case studies in how new systems emerge in response to demographic pressures, technological innovations, and changing values. These transformations, in turn, explain many of the underlying forces shaping the modern world.

- Analyzing such changes can also uncover deep-rooted links between current systems and their historical precursors. For instance, by tracing the lineage of today’s corporate structures and trade networks, we develop a richer understanding of industrialization, globalization, and financial regulation.

- This analytical lens is particularly useful in understanding the rise and fall of civilizations, the formation of national identities, and the shifting balance of political ideologies across continents.

- Additionally, interdisciplinary approaches—incorporating economics, sociology, political theory, and environmental science—allow students to construct dynamic models of long-term societal evolution. For example, the study of agrarian economies transitioning into industrial systems provides a backdrop to modern frameworks like industrial ecology and the circular economy.

Preserving Cultural Heritage

- Civilizations pass on their values, beliefs, knowledge, and artistry through both tangible and intangible forms. Understanding and documenting these aspects ensures that future generations retain access to their collective roots, even as societies continue to evolve.

- Language preservation, traditional performing arts, architectural practices, culinary rituals, and religious customs are all key elements of cultural continuity. These inherited forms of expression act as bridges across time, linking individuals to their ancestors and anchoring communities in shared meaning.

- Educational efforts that focus on documenting and curating artistic and cultural practices—such as oral epics, ceremonial dances, or visual symbols—serve not only to honor past achievements but also to inspire innovation in the present.

- Institutions such as UNESCO’s World Heritage program highlight and protect places of outstanding universal value, ensuring that monuments, urban layouts, and sacred sites remain accessible to humanity as repositories of wisdom and identity.

- Platforms like arts, design, and media studies offer modern tools to reinterpret and re-present these legacies, while cultural studies frameworks provide the critical lens to examine power, appropriation, and authenticity in heritage work.

- Safeguarding cultural memory is not merely about nostalgia; it strengthens social cohesion, promotes intergenerational dialogue, and equips communities to navigate modern challenges by drawing from enduring wisdom.

Learning from the Past

- Insights from earlier eras help policymakers, scientists, and educators craft solutions that account for human behavior, societal complexity, and unintended consequences. By reviewing both triumphs and failures from the past, communities can make more informed choices in the present.

- Patterns of resilience, adaptation, and conflict management offer models that are still applicable in today’s rapidly changing global landscape. Whether responding to technological disruption, social inequality, or public health crises, these precedents provide valuable strategic guidance.

- For instance, the comparative study of pandemics—ranging from the Black Death to the 1918 influenza and COVID-19—demonstrates the evolution of public health infrastructure, scientific understanding, and government response mechanisms.

- Similarly, the outcomes of past policy interventions can shed light on long-term effects in areas such as taxation, welfare systems, education reform, and urban planning. Tools like policy analysis build on these lessons to craft more resilient frameworks for the future.

- Analyzing conflict resolution efforts, civil rights movements, and diplomatic strategies also empowers individuals to approach modern challenges with both moral clarity and empirical depth. This kind of applied retrospection nurtures critical thinking and ethical awareness—essential traits for leadership and civic responsibility.

- Ultimately, drawing lessons from prior generations provides a foundation for progress. It allows societies to avoid repeating errors, to value tested principles, and to appreciate the diversity of solutions developed under varying constraints and conditions.

Approaches to Studying History

Chronological Approach

- Organizing historical events in sequential order to analyze cause-and-effect relationships.

- Example: Timeline of major world wars.

This educational graphic visually explains the chronological approach to historical study. It presents a clear timeline of major world wars—World War I (1914–1918), World War II (1939–1945), and a hypothetical future war—positioned along an arrow indicating the passage of time. Each event is symbolized with imagery such as a biplane, a tank, and a mushroom cloud to highlight technological and destructive evolution. This approach helps students and researchers analyze how past events influence subsequent developments, fostering a deeper understanding of historical causality and continuity. Ideal for curriculum materials and history education websites.

Thematic Approach

- Exploring specific themes, such as gender, religion, or technology, across different periods.

- Example: The role of religion in political revolutions.

Comparative History

- Comparing different societies or time periods to identify patterns and contrasts.

- Example: Comparing the Industrial Revolution in Britain and Japan.

This visual learning aid highlights the comparative history approach, a method that investigates patterns and contrasts between different societies or time periods. The image contrasts Britain’s early industrial landscape—with a steam-powered factory and smokestacks—against Japan’s industrial revolution, symbolized by traditional architecture and militant figures wielding rifles and flags. The layout guides viewers from one context to the other, emphasizing cross-cultural historical analysis. This illustration is ideal for history educators explaining how to use comparative frameworks to understand global transformations like the Industrial Revolution.

Microhistory

- Focusing on specific individuals, communities, or events to provide detailed insights.

- Example: The life of a medieval peasant or a single village during the Renaissance.

This sepia-toned educational graphic introduces the microhistorical approach to studying history. The image centers on a solitary medieval peasant holding a pitchfork, standing before a small Renaissance village with rustic homes and a chapel, evoking themes of everyday life in the past. The visual emphasizes how microhistory investigates narrow yet rich historical subjects—such as the experience of a single villager or small community—to reveal deeper cultural, economic, and social patterns. Ideal for academic resources and history instruction that highlights the value of close, contextual analysis in understanding the broader historical narrative.

Key Fields in History

Political History

- Examines governance, power structures, and political ideologies over time.

- Focus Areas:

- Evolution of political systems, such as monarchies and democracies.

- Analysis of revolutions and reforms, like the French Revolution or the Civil Rights Movement.

- Applications:

- Informing modern governance and international relations.

Military History

- Focuses on wars, strategies, and the impact of military conflicts on societies.

- Key Topics:

- Major conflicts like World War I and II.

- Technological advancements in warfare, such as the development of nuclear weapons.

- Applications:

- Understanding the causes of conflict and promoting peace-building efforts.

Economic History

- Analyzes the development of economies, trade, and industry across time.

- Focus Areas:

- The impact of the Industrial Revolution on global economies.

- The rise and fall of trade empires, such as the Silk Road or the British Empire.

- Applications:

- Providing insights into modern economic policies and globalization.

Social History

- Explores the lives of ordinary people, focusing on class, gender, and cultural practices.

- Key Topics:

- The feminist movement and the evolution of women’s rights.

- The effects of urbanization during the 19th century.

- Applications:

- Informing policies on social equity and cultural preservation.

Cultural History

- Investigates the evolution of ideas, art, and intellectual movements.

- Focus Areas:

- The Renaissance as a cultural rebirth in Europe.

- The impact of modern media on shaping public opinion.

- Applications:

- Enhancing cross-cultural understanding in a globalized world.

Approaches to Researching the Past

Primary Source Investigation

- At the heart of all inquiry into earlier times is the close examination of original records created during the period under study. These firsthand materials serve as direct evidence of social, political, cultural, and economic developments.

- Examples include personal letters revealing private sentiments, court transcripts capturing the legal thinking of a time, newspapers documenting contemporary reactions to major events, and tools or household items used in everyday life.

- Researchers must assess these materials critically, considering their authorship, context, and purpose. For instance, a propaganda poster offers insight not just into what was communicated, but into the mindset and strategy of its creators.

- Such sources are often scattered across libraries, government archives, religious institutions, and private collections, requiring both detective work and a deep understanding of the time period’s language and customs.

Interpretive Analysis Through Secondary Material

- Once primary documents are gathered, the next step often involves reviewing works created by scholars who have already studied those same materials. These authors offer interpretations, contextual frameworks, and thematic syntheses that help shape broader understanding.

- Examples include peer-reviewed articles that debate causes of revolutions, biographical essays that explore the life of a political leader, and documentaries that present reconstructed narratives based on curated evidence.

- These materials allow emerging researchers to identify gaps in existing knowledge, challenge prevailing assumptions, and situate their own work within ongoing academic conversations.

- Engaging critically with secondary interpretations develops one’s ability to think comparatively and analytically, moving beyond mere summary toward deeper argumentation.

Preserving and Recording Living Memory

- In addition to written and material records, one of the richest sources of insight into the past is the spoken testimony of individuals who experienced key events. These oral narratives are particularly valuable for capturing marginalized or local perspectives often absent from official documents.

- Examples include conversations with survivors of war, displaced persons recounting migration stories, or elderly residents describing how their communities evolved over time.

- Researchers must be sensitive and well-prepared, employing ethical interview techniques and careful transcription to preserve authenticity. Attention to tone, emotion, and non-verbal cues is essential.

- Oral documentation often reveals cultural beliefs, community dynamics, and personal resilience in ways that complement traditional archival material.

Technology-Enhanced Inquiry into the Past

- The digital revolution has transformed the study of earlier times. Powerful tools now allow researchers to store, search, analyze, and present massive amounts of information across formats and disciplines.

- Examples include geographic information systems (GIS) used to map ancient trade routes, machine learning models that analyze speech patterns in political speeches, and digital reconstructions of ruined architectural sites.

- Online archives, digitized newspapers, and crowd-sourced transcription platforms have made rare and fragile materials more accessible to scholars worldwide.

- Equally important is the use of digital storytelling techniques—such as virtual reality tours or interactive timelines—to bring the study of earlier civilizations and events to wider audiences, including students and the general public.

Challenges in Exploring the Past

Bias and Subjectivity

- One of the most persistent obstacles in analyzing past narratives is the presence of bias—both intentional and unconscious. Every record or account is shaped by the creator’s worldview, access to information, and cultural or political context. This subjectivity can color what events are emphasized, whose voices are highlighted, and which interpretations become dominant.

- For example, accounts from colonial administrators often reflect the priorities of imperial governance, frequently omitting or downplaying the experiences of colonized populations. In such cases, the record becomes a tool of power, reinforcing hierarchies rather than providing an impartial view of events.

- Moreover, modern scholars must remain alert to their own interpretive lenses. Whether influenced by national identity, academic trends, or ideological beliefs, present-day researchers risk introducing contemporary assumptions into their analysis of earlier periods.

- Correcting these imbalances requires active engagement with alternative perspectives—such as indigenous oral traditions, folk narratives, and material culture—which challenge dominant narratives and reintroduce lost or silenced voices into the discourse.

- For example, in the examination of colonial and post-colonial systems, it is essential to include the viewpoints of native populations, local leaders, and cultural mediators whose stories often contradict official records.

Incomplete Records and Lost Narratives

- Another major challenge in reconstructing the past is the sheer inconsistency and fragmentation of surviving documentation. Entire populations, events, or time periods may be represented by only a few fragmented sources—if any at all. These gaps make it difficult to form a complete picture of social dynamics, personal experiences, or cultural transitions.

- Losses may occur through the decay of materials, natural disasters, war, censorship, or deliberate destruction of evidence. Even where documentation exists, it may be scattered across inaccessible archives or remain untranslated.

- Marginalized communities—such as enslaved peoples, laborers, rural populations, or ethnic minorities—often leave behind limited written traces. In such cases, the absence of formal records does not imply a lack of significance, but rather reflects systemic exclusion from the mechanisms of documentation.

- To address this, scholars increasingly turn to unconventional sources: architecture, agricultural patterns, oral traditions, textile designs, and musical heritage. These indirect records can illuminate aspects of everyday life that traditional archives overlook.

- For instance, the limited visibility of marginalized groups in official archives has prompted researchers to develop interdisciplinary techniques combining archaeology, linguistics, and anthropology to recover their stories.

Interpretation, Change, and the Politics of Memory

- Our understanding of past events is never static. As new evidence comes to light or as societal values shift, previous conclusions are revisited, reevaluated, and sometimes overturned. This dynamic nature of interpretation is both a strength and a complication in the study of earlier times.

- Interpretative change may emerge from the discovery of new documents, fresh archaeological data, or a re-reading of known texts through different theoretical lenses—such as feminist, post-colonial, or environmental frameworks. The result is an evolving conversation in which no single version of events holds eternal authority.

- Such revisions often spark debate. While some view reinterpretation as necessary and progressive, others see it as an ideological intrusion. The tension between traditional narratives and contemporary perspectives is especially visible in debates over national identity, cultural monuments, and educational curricula.

- One example is the re-examination of gender roles in past societies. Recent scholarship on women’s contributions to political and social movements has dramatically expanded our understanding of their agency, participation, and influence, which were long underrepresented in formal accounts.

- Understanding that our knowledge of the past is constructed—and often reconstructed—underscores the importance of maintaining a critical, reflective approach and welcoming interdisciplinary insights to continually refine our collective memory.

Practical Applications of Studying the Past

Education and Lifelong Learning

- Integrating past events and societal developments into educational curricula equips students with essential tools for critical inquiry. Learners are encouraged to evaluate sources, identify bias, and synthesize diverse viewpoints—skills that are crucial not only for academic achievement but for informed participation in civic life.

- By exploring how communities, ideologies, and institutions have evolved, students gain a nuanced understanding of change, continuity, and complexity. These concepts are transferable to disciplines ranging from political science and economics to the arts and environmental studies.

- Additionally, teaching materials that incorporate timelines, case studies, archival documents, and reenactments foster engagement and creativity. Visual storytelling, role-based simulations, and interdisciplinary projects enable learners to inhabit different perspectives and grapple with moral and ethical dilemmas faced by individuals in prior generations.

- Educational strategies that draw on past experiences also support media literacy, helping students recognize patterns in propaganda, misinformation, and persuasive narratives that shape modern discourse.

Policy Development and International Diplomacy

- Governments and global organizations often rely on detailed analyses of earlier conflicts, treaties, and power shifts to guide contemporary policymaking. Understanding how similar issues were handled—or mishandled—in the past can illuminate the roots of modern challenges and offer guidance for resolution.

- For instance, insights from border realignments, peace negotiations, or failed alliances help diplomats anticipate the consequences of international agreements. Case studies from post-conflict reconstruction efforts or transitional justice models also shape legal frameworks for peacebuilding and reconciliation.

- Public health policy, economic planning, and legal reform can all benefit from retrospective evaluations. Policymakers may examine the outcomes of previous interventions in areas such as taxation, welfare, land rights, or environmental regulation to avoid repeating mistakes and improve future strategies.

- Understanding the precedents behind issues like migration, sovereignty, and inter-ethnic tensions can reduce misunderstandings and foster cross-cultural dialogue. For example, knowledge of long-standing treaties can clarify contemporary territorial disputes, and past trade agreements can inform regional integration efforts.

Cultural Preservation and Identity Formation

- Examining traditions, ancestral practices, and architectural legacies helps societies protect their heritage and pass on cultural knowledge to future generations. This work involves safeguarding not just physical monuments but also languages, rituals, and worldviews that define community identity.

- Collaborations between researchers, local communities, and policymakers enable the mapping and documentation of intangible cultural practices, such as oral storytelling, religious festivals, and indigenous ecological knowledge. These efforts sustain cultural continuity in the face of modernization and globalization.

- Conservation of ancient sites, traditional craftsmanship, and endangered dialects supports tourism, education, and intergenerational bonding. Programs that revitalize ancestral arts—such as textile weaving, music, or culinary traditions—strengthen community resilience and pride.

- Organizations like UNESCO and national heritage boards invest in archiving and digitalizing materials to ensure accessibility for future researchers and educators, making cultural preservation an increasingly collaborative and technologically supported endeavor.

Public Awareness and Civic Engagement

- Popular media and public institutions play a crucial role in making the past accessible to diverse audiences. Museums, exhibitions, and guided heritage tours serve as educational spaces where people can connect with their collective roots and reflect on national or global narratives.

- Historical fiction, biographical films, and documentary series stimulate public interest by bringing complex events to life through compelling storytelling. These forms of media can spark curiosity, empathy, and debate, drawing attention to lesser-known figures and overlooked perspectives.

- Anniversaries, commemorative events, and reenactments provide opportunities for communities to honor milestones, celebrate resilience, and confront difficult legacies. Public engagement in such events fosters dialogue, remembrance, and social cohesion.

- Digital platforms, including virtual museums and open-access archives, further democratize access to knowledge. They enable students, educators, and curious individuals to explore source material, timelines, and oral testimonies at their own pace and from anywhere in the world.

Emerging Frontiers in the Study of the Past

Interdisciplinary Approaches to Understanding Human Experience

- The future of academic inquiry into earlier periods increasingly depends on integrating perspectives from multiple disciplines. While traditional archival analysis remains foundational, scholars are now drawing on tools and methods from fields such as anthropology, archaeology, linguistics, and even neuroscience to gain richer insights into how societies formed, evolved, and interacted.

- For example, archaeological excavations often provide the physical context missing from written records, revealing patterns of settlement, trade, and material culture. Anthropological studies, on the other hand, allow researchers to interpret symbolic systems, rituals, and oral traditions that may not be documented in official texts.

- Interdisciplinary collaboration also opens new pathways for understanding long-term processes such as urbanization, migration, or social stratification. When environmental data is paired with textual records, for instance, it becomes possible to reconstruct how ecological pressures influenced political stability or technological innovation.

- These converging methodologies not only improve accuracy but also foster creativity in research design, encouraging scholars to ask new questions that cut across time, space, and culture.

Global Perspectives and Decolonizing Knowledge

- As academic institutions and research centers become more inclusive and internationally networked, a growing emphasis is placed on examining the human past through a truly global lens. This means moving beyond the long-dominant Euro-American narratives to foreground the experiences, contributions, and epistemologies of non-Western societies.

- Decolonizing research involves rethinking assumptions embedded in source selection, methodology, and interpretation. Scholars increasingly turn to local oral traditions, regional languages, and indigenous ways of knowing as valid and necessary sources of insight. These shifts broaden the scope of academic inquiry and challenge previously accepted chronologies and value systems.

- Incorporating diverse perspectives also reveals patterns of interaction—such as trade, conquest, diplomacy, and cultural exchange—that have shaped global development. Studies of East African city-states, South Asian maritime networks, or Andean agricultural systems help reconstruct a more interconnected and accurate picture of the past.

- Expanding global perspectives also aligns with emerging pedagogical priorities, offering students a more inclusive and representative view of the world’s civilizational heritage. Pages like cultural history provide a launching point for these critical explorations.

Digital Humanities and Computational Discovery

- Digital technologies are transforming the way scholars engage with large-scale evidence from previous eras. Through advancements in machine learning, text mining, and data visualization, researchers can now process thousands of documents, maps, or artifacts to detect trends, correlations, and anomalies that might otherwise remain hidden.

- For instance, natural language processing (NLP) can extract recurring themes or sentiments across political speeches, legal codes, or diplomatic correspondence. Tools like GIS (Geographic Information Systems) allow for spatial analysis of empire expansion, trade networks, or settlement patterns.

- Big data approaches are particularly useful in uncovering hidden narratives within colonial archives, censuses, and court records—revealing how marginal groups navigated official systems or how social movements gained momentum across different regions.

- Disciplines such as artificial intelligence and data science are now central to many research projects focused on the past. They empower teams to build interactive models, simulate historical processes, and engage wider audiences through immersive platforms.

Environmental Dimensions of the Past

- In light of today’s global ecological crises, many researchers are revisiting past human-environment relationships to better understand how climate, geography, and resource use shaped societal development. This growing area of study focuses on how communities adapted to or failed to respond to environmental pressures such as droughts, deforestation, and disease.

- Environmental archives—like ice cores, pollen samples, and tree rings—offer climate scientists and historians alike new ways to reconstruct agricultural practices, population shifts, and infrastructure collapse. Paired with economic records and archaeological data, these methods provide a multidimensional view of sustainability across time.

- Case studies from civilizations that faced ecological tipping points—such as the collapse of the Maya cities or the Dust Bowl migration—highlight the interplay between environmental stress and social resilience. These examples are highly relevant to current discussions on sustainability and disaster preparedness.

- Platforms like environmental economic research bridge the gap between past adaptations and modern policy debates, reinforcing the importance of historical perspective in climate planning and environmental justice.

From Empires to Revolutions: Why the Past Still Shapes Us

Understanding How the Past Shapes the Present

Developing Critical Thinking and Analytical Skills

Exploring Diverse Cultures, Ideas, and Perspectives

Learning to Research, Write, and Communicate Effectively

Preparing for Versatile and Meaningful Career Opportunities

History – Frequently Asked Questions

What is History as a field of study, and how is it different from simply learning dates and events?

History as a field of study is the critical investigation of past societies, ideas, conflicts, and everyday lives using evidence from documents, artefacts, images, and oral accounts. It goes far beyond memorising dates and events: historians ask why things happened, how different causes and perspectives interact, and what long-term patterns or turning points we can identify. Studying History trains you to interpret evidence, question assumptions, and understand how narratives about the past are constructed.

What are the main branches or subfields of History I might encounter at university?

At university, you may encounter many subfields, such as political history, social history, economic history, cultural history, intellectual history, religious history, gender history, legal and constitutional history, global and transnational history, and histories of empire, colonialism, and decolonisation. Many programmes also offer themed modules on war and diplomacy, revolutions, migration, environment, science and technology, or the history of ideas.

What kinds of skills does studying History develop?

History develops a wide range of transferable skills. You learn to analyse primary and secondary sources, evaluate conflicting interpretations, and build evidence-based arguments in clear written and spoken form. You also practise planning research, managing large amounts of information, referencing sources correctly, and reflecting critically on your own assumptions. These skills are valuable across many academic disciplines and careers.

How does the History hub on Prep4Uni.online help me prepare for university study?

The History hub on Prep4Uni.online is designed as a gateway into more specialised areas such as cultural history, economic history, political power, trade and globalisation, and the history of ideas. It offers guiding questions, connections to related topics, and examples that encourage you to think like a historian. You can use the hub to explore themes, practise linking different topics, and get a sense of the breadth of university-level History.

What types of sources do historians use, and how are they evaluated?

Historians use primary sources like letters, official records, diaries, speeches, newspapers, visual images, artefacts, and oral testimonies, as well as secondary sources like scholarly books and articles. They evaluate sources by asking who produced them, for what audience, in which context, and with what biases or silences. Students learn to compare sources, cross-check evidence, and weigh how reliable or representative each piece of material may be.

How is university-level History assessed?

University-level History is usually assessed through essays, document commentaries, exam questions, group presentations, and longer research projects or dissertations. Assessment tasks focus on your ability to construct clear arguments, use evidence effectively, engage with historians’ debates, and write in a structured and precise way. Preparatory work on Prep4Uni.online can help you practise these forms gradually before you enter a degree programme.

What careers can a History background lead to?

History graduates work in a wide range of careers. Common paths include education, museums and heritage, archives, publishing, journalism, public policy, law, business and management, international organisations, and research or consultancy. Employers value History graduates for their critical thinking, writing ability, and capacity to understand complex social and political contexts.

How does History connect with other Humanities and Social Sciences subjects?

History connects closely with fields such as political science, economics, sociology, anthropology, cultural studies, religious studies, and law. For example, economic history complements economics by adding long-term context to market and policy changes, while cultural history overlaps with literature and media studies in analysing texts and images. The Prep4Uni.online structure is designed to help you trace these links across different hub pages.

Is History mainly focused on Western or European topics?

Many contemporary History programmes strive to move beyond a narrow Western focus by including global, regional, and comparative perspectives. You may study histories of Asia, Africa, the Middle East, the Americas, and the Pacific, as well as global connections through trade, empire, migration, and cultural exchange. Prep4Uni.online encourages you to think about History in an interconnected way, linking local case studies to wider global patterns.

What can I do now to strengthen my preparation for a History degree?

You can start by reading beyond your school syllabus: short history books, accessible biographies, and well-researched documentaries. Practise writing short essays that answer “why” and “how” questions rather than simply describing events. Use the Prep4Uni.online History hub to explore thematic pages, compare different historical interpretations, and keep a study notebook where you summarise arguments and evidence in your own words.

How does studying History help me understand current events and public debates?

History shows that current events always have deeper roots. By studying patterns of conflict, reform, migration, technological change, and social movements, you can see how today’s debates about identity, inequality, globalisation, and climate are shaped by earlier choices and structures. This historical perspective helps you think more critically about news, policy proposals, and public narratives in the present.

Do I need to be good at memorising dates to succeed in History?

A basic sense of chronology is important, but success in History depends much more on understanding causes, consequences, and interpretations than on memorising long lists of dates. Prep4Uni.online materials aim to help you see how key turning points fit into broader stories, so that dates become meaningful markers within an argument rather than isolated facts to remember.

History Condensation

History is more than a record of the past; it is a guide to understanding the complexities of human civilization. By examining the triumphs and tragedies, the innovations and conflicts, history equips us to navigate the challenges of today and shape a better future. Its interdisciplinary and evolving nature ensures its continued relevance in a rapidly changing world. As we delve into the past, we uncover not only the stories of others but also our shared humanity, fostering a sense of connection and purpose that transcends time.

History: Self-Assessment Questions

1. What is history and why is it important to study it?

Answer: History is the systematic study of past events, cultures, and societies, providing a record of human experiences and achievements. It is important because it helps us understand how past decisions, conflicts, and innovations have shaped the present world. Studying history enables us to learn from past mistakes and successes, informing better decisions for the future. Moreover, history enriches our cultural identity and fosters critical thinking by challenging us to analyze complex causes and consequences over time.

2. How do historians gather and interpret evidence?

Answer: Historians gather evidence from a variety of sources including archival documents, oral histories, artifacts, and digital records. They critically analyze these sources to construct an accurate narrative of past events. This process involves evaluating the reliability, context, and perspective of each source. By interpreting evidence carefully, historians can reconstruct events and understand the underlying factors that influenced them, providing a nuanced view of history.

3. What methodologies are commonly used in historical research?

Answer: Historical research commonly employs methodologies such as archival research, comparative analysis, and interdisciplinary approaches. These methods allow historians to cross-check sources, identify patterns, and place events within broader social, cultural, and political contexts. Archival research involves examining primary documents, while comparative analysis helps highlight similarities and differences between historical events or periods. Together, these methodologies ensure a rigorous, comprehensive understanding of the past.

4. How does the study of history contribute to critical thinking?

Answer: The study of history contributes to critical thinking by requiring the evaluation of multiple perspectives and the analysis of complex cause-and-effect relationships. It challenges students to question established narratives and to consider how historical interpretations are shaped by cultural and ideological biases. Through examining differing accounts and evidence, learners develop the ability to assess the validity of sources and arguments. This analytical process not only deepens their understanding of the past but also equips them with the skills to tackle contemporary issues critically.

5. In what ways can historical events influence modern society?

Answer: Historical events influence modern society by laying the groundwork for current political systems, cultural norms, and social structures. The decisions made and conflicts resolved in the past continue to resonate, affecting everything from laws and governance to societal values and technological progress. Understanding these events allows us to comprehend the origins of current challenges and to appreciate the evolution of human thought and behavior. This awareness helps individuals and societies learn from history and make informed choices for the future.

6. What challenges do historians face in reconstructing the past?

Answer: Historians face challenges such as incomplete records, biased sources, and conflicting interpretations of events. The fragmentary nature of historical evidence often requires careful cross-referencing and critical evaluation to form a coherent narrative. Additionally, historians must contend with the subjectivity inherent in sources that were created with particular perspectives or agendas. Despite these challenges, rigorous methodologies and interdisciplinary approaches help historians mitigate bias and produce well-substantiated interpretations of the past.

7. How does understanding history help in shaping public policy?

Answer: Understanding history helps shape public policy by providing insights into the outcomes of previous decisions and societal trends. Policymakers can learn from historical successes and failures to design more effective and informed strategies for addressing current issues. The lessons of history offer valuable perspectives on governance, conflict resolution, and social change. By applying historical insights, public policies can be crafted to avoid past mistakes and to promote a more stable and just society.

8. What is the significance of primary sources in historical research?

Answer: Primary sources are of great significance in historical research because they provide firsthand accounts of past events. These sources, such as letters, photographs, and official documents, offer direct evidence that helps to reconstruct historical narratives accurately. Their authenticity and immediacy allow historians to gain insights into the thoughts, feelings, and motivations of people from the past. Analyzing primary sources is essential for developing a credible and detailed understanding of historical contexts.

9. How do historians address bias in historical narratives?

Answer: Historians address bias in historical narratives by critically analyzing the sources and considering the context in which they were produced. They compare multiple accounts, assess the motivations behind the creation of the sources, and apply various theoretical frameworks to understand different perspectives. This rigorous process helps to uncover underlying biases and to construct a more balanced and nuanced interpretation of events. Through careful cross-examination and validation, historians work to minimize bias and present an objective account of the past.

10. How does interdisciplinary research enhance the study of history?

Answer: Interdisciplinary research enhances the study of history by integrating perspectives and methods from fields such as sociology, archaeology, and economics. This approach allows historians to develop a more comprehensive understanding of historical events and societal trends by examining them through multiple lenses. It enriches the analysis by incorporating diverse data sources and theoretical insights, leading to more robust and multifaceted interpretations. By breaking down disciplinary boundaries, interdisciplinary research fosters innovative perspectives that contribute significantly to our understanding of the past.

History: Inquisitive Questions

1. How might digital archives and online databases transform historical research in the 21st century?

Answer:

Digital archives and online databases are revolutionizing historical research by vastly increasing access to primary sources and archival materials that were once confined to physical locations. Researchers can now retrieve vast amounts of information quickly and efficiently, enabling more comprehensive and comparative studies across different periods and regions. This accessibility not only democratizes historical research but also allows for innovative methodologies, such as digital text analysis and data mining, which can reveal patterns and trends that were previously unnoticed. As a result, digital archives are reshaping how historians conduct research, fostering a more interconnected and dynamic approach to understanding the past.

In addition, the digitalization of historical records supports collaborative research by enabling scholars from around the world to share data and insights seamlessly. This global exchange of information can lead to more interdisciplinary studies and new interpretations of historical events. However, it also raises challenges related to digital preservation, data integrity, and ethical considerations regarding the accessibility of sensitive information. Addressing these challenges is crucial for ensuring that digital archives continue to serve as reliable and comprehensive resources for future generations of historians.

2. In what ways can the study of history inform our understanding of contemporary social and political issues?

Answer:

The study of history informs our understanding of contemporary social and political issues by providing a context for the development of current societal structures and conflicts. Historical analysis reveals how past events, policies, and cultural movements have shaped modern institutions and social norms, allowing us to trace the evolution of ideas and practices over time. This deep contextual knowledge is invaluable for interpreting current events, as it highlights recurring patterns and potential outcomes based on historical precedents. By examining historical case studies, we can better appreciate the complexities of modern issues and develop more informed strategies for addressing them.

Furthermore, historical inquiry encourages critical thinking and a questioning of dominant narratives, which can lead to more balanced perspectives on contemporary debates. It also helps to identify the root causes of social inequalities and conflicts, providing insights that can inform policy-making and social reform. Ultimately, the integration of historical perspectives into the analysis of current events enhances our ability to navigate present challenges with a more nuanced and evidence-based approach, fostering a deeper understanding of the underlying forces at play.

3. How might globalization impact the interpretation and teaching of history in multicultural societies?

Answer:

Globalization significantly impacts the interpretation and teaching of history by bringing a multitude of perspectives into the classroom and challenging traditional, often Eurocentric narratives. In multicultural societies, the global exchange of ideas and cultural practices encourages educators to incorporate diverse viewpoints, ensuring that historical accounts reflect the experiences and contributions of all communities. This broadened perspective enriches students’ understanding of the past by highlighting the interconnectedness of different cultures and the global nature of historical events. It also promotes critical thinking by encouraging learners to analyze how history is constructed and to question whose stories are prioritized in mainstream narratives.

Moreover, globalization can lead to the development of more inclusive curricula that integrate digital resources and collaborative projects, fostering an environment of cross-cultural dialogue and mutual understanding. However, it also presents challenges, such as reconciling conflicting historical accounts and addressing cultural sensitivities. Educators must navigate these complexities by adopting flexible teaching methods that honor diverse cultural heritages while promoting a comprehensive understanding of history. Ultimately, globalization reshapes the way history is taught, making it more dynamic, inclusive, and relevant to contemporary global realities.

4. What challenges do historians face when reconciling conflicting narratives from diverse cultural perspectives?

Answer:

Historians face significant challenges when reconciling conflicting narratives from diverse cultural perspectives due to the inherent subjectivity of historical sources and the influence of cultural bias. Different communities often have varying accounts of the same events, shaped by their unique experiences, values, and social contexts. These divergent narratives can lead to disputes over historical interpretations and the representation of truth. Historians must critically evaluate sources, consider the context in which they were produced, and reconcile discrepancies by seeking common ground or highlighting the diversity of experiences.

Addressing these challenges requires a rigorous and transparent methodology that includes cross-referencing multiple sources and employing interdisciplinary approaches. Historians also need to remain sensitive to the power dynamics and ethical implications of privileging one narrative over another. By engaging in open dialogue with communities and incorporating a variety of voices, scholars can produce more balanced and inclusive accounts of history. This process is complex and often iterative, but it is essential for achieving a comprehensive understanding of the past that respects cultural diversity.

5. How can historical research contribute to social justice and the empowerment of marginalized communities?

Answer:

Historical research can contribute to social justice by uncovering the overlooked or suppressed narratives of marginalized communities, thereby challenging dominant power structures and providing a voice to those who have been historically silenced. By documenting and analyzing the struggles, achievements, and contributions of marginalized groups, historians can highlight systemic inequalities and inspire movements for social change. This research not only enriches our understanding of the past but also serves as a foundation for advocacy, helping to inform policies that address historical injustices and promote equity. It empowers communities by validating their experiences and preserving their cultural heritage for future generations.

Furthermore, by engaging with the histories of marginalized communities, public discourse can be transformed to include more diverse perspectives, leading to more inclusive narratives in education, media, and politics. This process helps to dismantle stereotypes and fosters a more equitable society where all voices are recognized and valued. Historical research, therefore, plays a vital role in advancing social justice by bridging the gap between past injustices and contemporary efforts to create a fairer and more inclusive world.

6. What role does memory play in shaping collective historical narratives and national identities?

Answer:

Memory plays a crucial role in shaping collective historical narratives and national identities by preserving the shared experiences, values, and traditions of a community. Collective memory influences how societies remember and interpret past events, often becoming a source of national pride or, conversely, of social tension. The way in which historical events are commemorated and taught can reinforce certain narratives while marginalizing others, thereby influencing contemporary identities and social cohesion. Memory, both individual and collective, is continuously constructed and reconstructed through education, media, and public rituals, which in turn shapes how communities understand themselves and their place in the world.

This dynamic process of memory construction is essential for the formation of national identities, as it provides a common framework for understanding a community’s history and shared values. However, it can also lead to contentious debates over whose memories are preserved and whose are forgotten. By critically examining the role of memory in history, scholars can offer insights into the power dynamics that shape collective narratives and contribute to more inclusive and representative historical accounts.

7. How might the digital age transform the methods used in historical research and teaching?

Answer:

The digital age is transforming historical research and teaching by providing new tools and methodologies that allow for the analysis, visualization, and dissemination of historical data on a massive scale. Digital archives, interactive timelines, and geospatial mapping enable historians to access and analyze vast collections of primary sources quickly and efficiently. These technologies facilitate more dynamic and collaborative research, as scholars from around the world can share findings and insights in real time. Additionally, digital tools are revolutionizing the classroom by making historical content more engaging through multimedia presentations, virtual field trips, and interactive learning modules.

In teaching, the digital age has made it possible to create more immersive and accessible educational experiences that cater to diverse learning styles. Online platforms and digital resources allow students to explore history beyond traditional textbooks, fostering a deeper understanding of complex events and trends. However, this shift also presents challenges, such as ensuring the accuracy of digital sources and addressing issues related to digital divide. Overall, the digital transformation in history has the potential to democratize knowledge and promote a more interactive and comprehensive approach to understanding the past.

8. What are the potential consequences of historical revisionism in contemporary society?

Answer:

Historical revisionism, which involves reinterpreting past events based on new evidence or perspectives, can have significant consequences for contemporary society. While it can lead to a more accurate and nuanced understanding of history, it also has the potential to create controversy and polarize public opinion if revisionist narratives challenge long-held beliefs or national myths. Such shifts in historical interpretation can influence collective memory, national identity, and public policy, sometimes leading to conflicts over whose version of history should be recognized and taught. The process of revisionism must therefore be handled with care, ensuring that it is based on rigorous research and respectful of multiple perspectives.

On the positive side, historical revisionism can uncover hidden truths and provide a more inclusive account of the past, giving voice to marginalized groups and fostering social justice. However, when misused, it can lead to the distortion of facts and the manipulation of historical narratives for political or ideological purposes. Balancing the need for an accurate historical record with the potential for revisionist controversy is a delicate task that requires ethical scholarship and open public discourse.

9. How can oral histories contribute to our understanding of historical events and cultural change?

Answer:

Oral histories are a vital resource for understanding historical events and cultural change because they capture the personal experiences, memories, and perspectives of individuals who lived through those events. This qualitative data provides insights into the emotional and social dimensions of history that are often absent from written records. Oral histories can reveal the impact of events on everyday life, offering a more intimate and humanized view of the past. They are especially valuable in documenting the histories of communities and groups whose voices may have been marginalized or overlooked in traditional historical accounts.

By incorporating oral histories into research, historians can create a more diverse and inclusive narrative that acknowledges the complexity of human experience. These narratives enrich our understanding of cultural change and provide a deeper context for interpreting historical events. Moreover, oral histories foster community engagement and help preserve cultural heritage by passing down stories from one generation to the next, thereby ensuring that the multifaceted dimensions of history are remembered and valued.

10. How might the study of material culture deepen our understanding of historical societies?

Answer:

The study of material culture, which involves analyzing artifacts, architecture, and other physical objects from the past, deepens our understanding of historical societies by providing tangible evidence of everyday life, technology, and social organization. Material culture offers insights into the economic, technological, and cultural practices of historical communities, revealing how they adapted to their environments and expressed their identities. By examining objects and structures, historians can reconstruct aspects of daily life that are not captured in written records, such as social hierarchy, trade networks, and cultural rituals.

This approach also helps to bridge the gap between abstract historical narratives and the lived experiences of people. Material culture serves as a direct link to the past, allowing researchers to interpret the practical and symbolic significance of artifacts in their historical context. Consequently, the study of material culture enriches our understanding of historical societies by providing a more nuanced and comprehensive picture of their development, values, and interactions with the broader world.

11. What challenges does the preservation of cultural heritage pose in the modern era, and how can these be addressed?

Answer:

The preservation of cultural heritage in the modern era poses challenges such as urbanization, climate change, and digital obsolescence, which can threaten the integrity and continuity of historical artifacts and sites. Rapid development and environmental degradation can lead to the loss of important cultural landmarks and traditional practices that are essential for understanding the past. Additionally, the transition from analog to digital media presents risks regarding data preservation and the accessibility of cultural records. Addressing these challenges requires comprehensive preservation strategies that combine traditional conservation techniques with modern technology, such as digital archiving and 3D modeling, to safeguard cultural heritage.

Collaborative efforts among governments, non-profit organizations, and local communities are also critical for implementing effective preservation programs. These initiatives must prioritize the documentation, restoration, and sustainable management of cultural assets, ensuring that they remain accessible for future generations. By fostering international cooperation and leveraging technological innovations, society can mitigate the risks to cultural heritage and promote a more sustainable approach to its preservation.

12. How might emerging trends in globalization influence the reinterpretation of historical narratives?

Answer:

Emerging trends in globalization are influencing the reinterpretation of historical narratives by challenging traditional, often Eurocentric perspectives and incorporating a broader range of voices and experiences. Global interconnectedness facilitates the exchange of cultural and historical knowledge, prompting scholars to re-examine historical events through diverse lenses that reflect the contributions of various regions and communities. This process of reinterpretation can lead to more inclusive and multifaceted narratives that better represent the complexity of global history. As a result, globalization not only broadens the scope of historical inquiry but also encourages a critical reassessment of established narratives.

Furthermore, the increased accessibility of global historical data through digital archives and international collaboration enhances the ability of researchers to compare and contrast different historical perspectives. This comparative approach fosters a more nuanced understanding of historical events and their long-term impacts on contemporary societies. The reinterpretation of historical narratives in a globalized context thus contributes to a richer, more equitable understanding of the past, which can inform present and future social, political, and cultural developments.