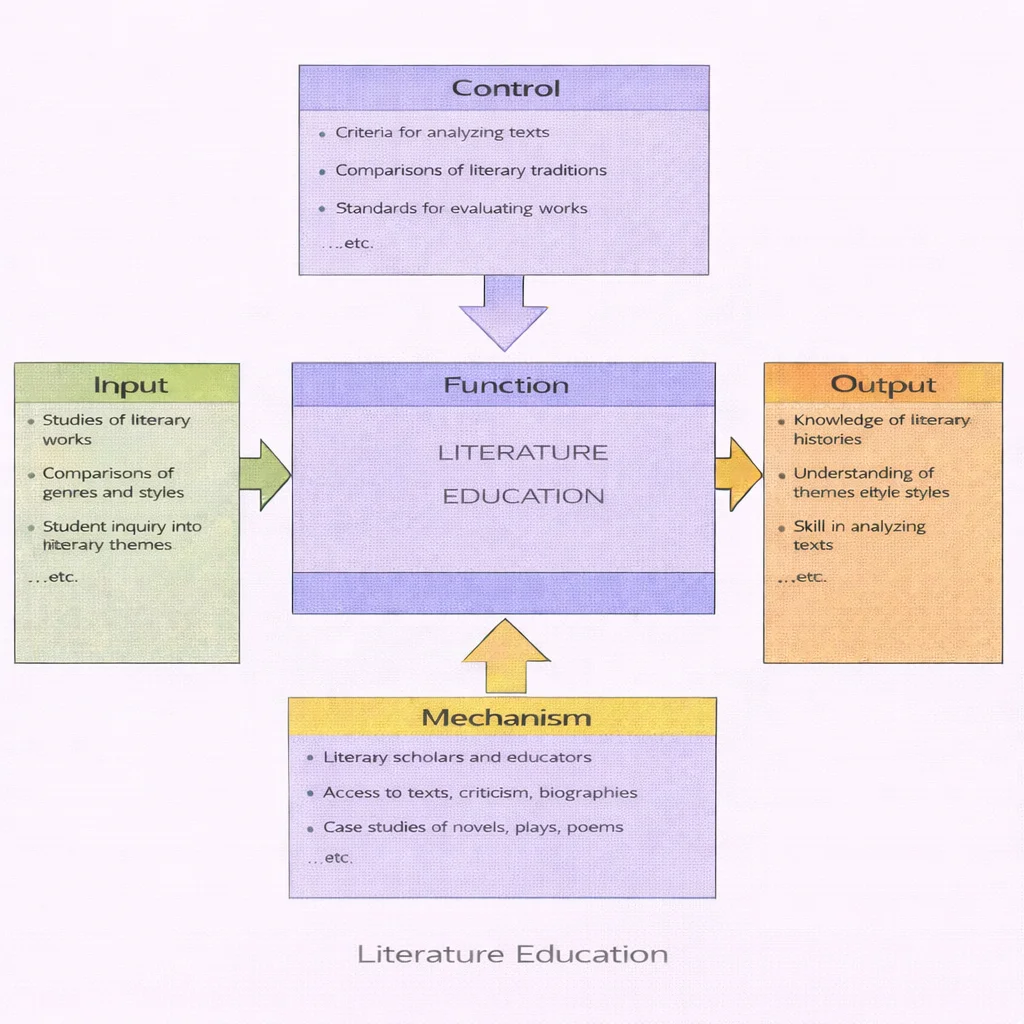

Literature Education, as shown here, is the process of turning encounters with poems, plays, and novels into disciplined understanding. Students begin with works, genres, and thematic questions as their raw material (inputs), but they do not read in a vacuum: their reading is guided by shared criteria, traditions of interpretation, and standards for judging arguments and evidence (controls). The work becomes possible and richer through the supports of educators, scholarship, and access to reliable texts and critical resources (mechanisms). When these pieces come together, learners move beyond “liking” or “disliking” a text and instead gain historical perspective, clearer insight into theme and style, and the transferable ability to analyze language and meaning with care (outputs).

Literature, as both a reflection and critique of human experience, provides a unique gateway into the heart of the humanities and social sciences. Through the study of prose, poetry, and drama, students examine how language shapes identity, history, and meaning across cultures and time. Literature often intersects with philosophy by probing into the nature of truth, morality, and existence, while also drawing from psychology to explore emotion, motivation, and the human condition.

A literary lens can help interpret the societal frameworks analyzed in sociology, where narratives serve as microcosms of class, race, gender, and power relations. Themes found in fiction often mirror real-world dynamics studied in political science, reflecting political ideologies, resistance, and reform. Likewise, spiritual themes and religious symbolism tie literature closely to religious studies, enabling a deeper appreciation of rituals, mythologies, and worldviews.

In the global context, literature reveals the cultural dimensions of diplomacy and conflict, aligning with studies in international relations. Stories are cultural artifacts that contribute to the collective imagination of a people, paralleling the kind of analysis used in evaluating internet and web technologies for digital storytelling and social discourse. Literature also becomes increasingly relevant in an age defined by emerging technologies and information technology, as authors imagine futures shaped by AI, automation, and ethical dilemmas.

Explorations of speculative fiction intersect with studies in robotics and autonomous systems and cybersecurity, while dystopian narratives probe into surveillance and control. Data-driven analysis of literary corpora links with data science and analytics and reflects growing interest in computational literary studies. Meanwhile, the mathematical underpinnings of meter, structure, and logic create intersections with mathematics and statistics.

Literature also dialogues with disciplines concerned with the built and natural environment. As narratives increasingly address ecological concerns and urban futures, students can find common ground with topics like environmental engineering and green building. The implications of climate change and disaster are themes also explored in earthquake and disaster engineering. Urban life, infrastructure, and planning often serve as rich narrative backdrops, tying literature to urban and regional planning.

From the speculative to the historical, literature helps illuminate the human impact of technologies like satellite technology and smart technologies. It can even help narrate industrial transitions, as reflected in smart manufacturing and renewable energy. In all these dimensions, literature remains a dynamic and resonant means of understanding humanity’s journey—its hopes, its fears, and its enduring questions.

This richly illustrated image presents literature as a source of imagination and cultural memory. At the center, an open book radiates light, with flowing, flame-like ribbons of color rising upward to suggest creativity, narrative energy, and the power of words. Around the book are portraits of writers and thinkers, theatrical masks, classical columns, and artistic icons, representing different genres and traditions—poetry, drama, fiction, and literary criticism. The dense collage-like composition conveys how literature connects many forms of human experience: emotion, history, philosophy, and social life, all woven together through language and storytelling.

- Humanities & Social Sciences topics:

- Overview

- Anthropology

- Cultural Studies

- History

- Literature

- Philosophy

- Political Science

- International Relations

- Psychology

- Religious Studies

- Sociology

- Linguistics

Table of Contents

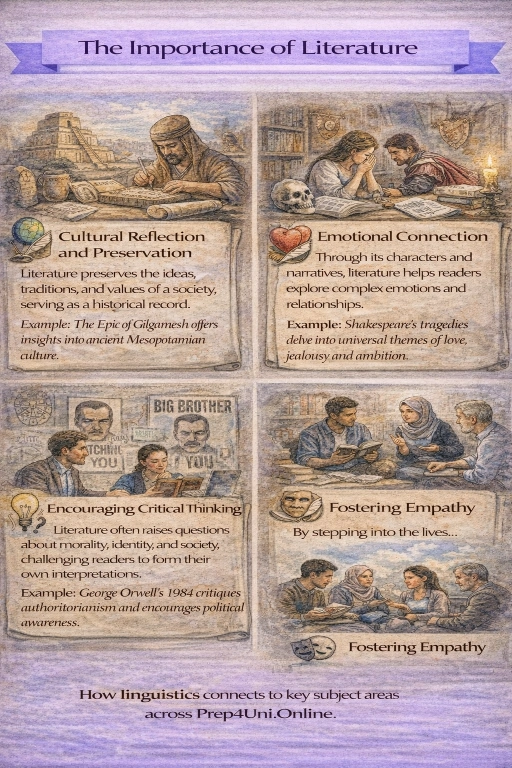

The Importance of Literature

Cultural Reflection and Preservation

- Literature preserves the ideas, traditions, and values of a society, serving as a historical record.

- Example: The Epic of Gilgamesh offers insights into ancient Mesopotamian culture.

Emotional Connection

- Through its characters and narratives, literature helps readers explore complex emotions and relationships.

- Example: Shakespeare’s tragedies delve into universal themes of love, jealousy, and ambition.

Encouraging Critical Thinking

- Literature often raises questions about morality, identity, and society, challenging readers to form their own interpretations.

- Example: George Orwell’s 1984 critiques authoritarianism and encourages political awareness.

Fostering Empathy

- By stepping into the lives of characters, readers gain a deeper understanding of perspectives different from their own.

- Stories make abstract struggles personal, helping readers feel the weight of choices, hopes, fears, and everyday dilemmas.

- Example: Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird invites readers to see injustice through a child’s eyes, strengthening moral awareness and compassion.

The importance of literature—preserving culture, deepening emotion, sharpening critical thought, and building empathy. A four-panel infographic that summarises why literature matters. It portrays (1) cultural reflection and preservation through an ancient writer and historical setting (e.g., The Epic of Gilgamesh), (2) emotional connection through intimate reading and conversation (e.g., Shakespearean tragedy), (3) encouraging critical thinking through themes of power and morality (e.g., Orwell’s 1984), and (4) fostering empathy through a diverse group exchanging perspectives and experiences.

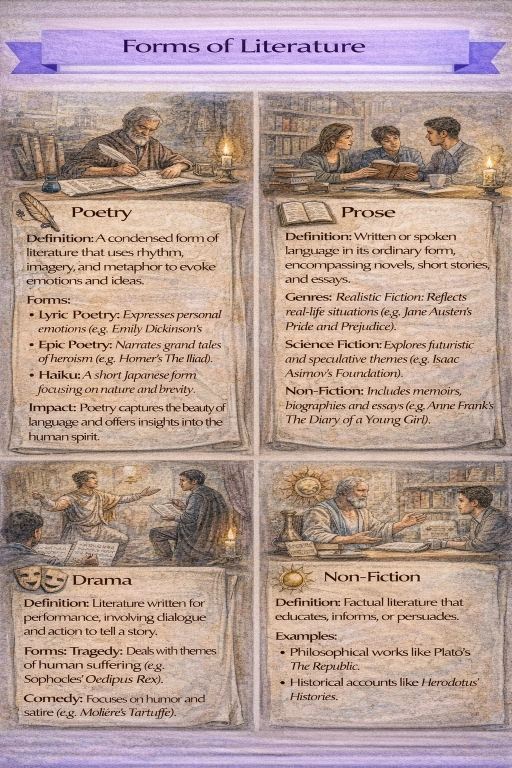

Forms of Literature

Poetry

- Definition: A condensed form of literature that uses rhythm, imagery, and metaphor to evoke emotions and ideas.

- Forms:

- Lyric Poetry: Expresses personal emotions (e.g., Emily Dickinson’s works).

- Epic Poetry: Narrates grand tales of heroism (e.g., Homer’s The Iliad).

- Haiku: A short Japanese form focusing on nature and brevity.

- Impact:

- Poetry captures the beauty of language and offers insights into the human spirit.

Prose

- Definition: Written or spoken language in its ordinary form, encompassing novels, short stories, and essays.

- Genres:

- Realistic Fiction: Reflects real-life situations (e.g., Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice).

- Science Fiction: Explores futuristic and speculative themes (e.g., Isaac Asimov’s Foundation).

- Non-Fiction: Includes memoirs, biographies, and essays (e.g., Anne Frank’s The Diary of a Young Girl).

Drama

- Definition: Literature written for performance, involving dialogue and action to tell a story.

- Forms:

- Tragedy: Deals with themes of human suffering (e.g., Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex).

- Comedy: Focuses on humor and satire (e.g., Molière’s Tartuffe).

- Impact:

- Drama combines literary artistry with visual performance to engage audiences.

Non-Fiction

- Definition: Factual literature that educates, informs, or persuades.

- Examples:

- Philosophical works like Plato’s The Republic.

- Historical accounts like Herodotus’ Histories.

This infographic presents four major literary forms in a 2×2 layout. Each section uses a painted scene (a writer with quill for Poetry, readers in discussion for Prose, actors on stage for Drama, and scholars in debate for Non-Fiction) paired with parchment-like text blocks. The panels outline what each form is, highlight common subtypes (e.g., lyric/epic/haiku for poetry; tragedy/comedy for drama), and include well-known examples such as The Iliad, Pride and Prejudice, Oedipus Rex, and The Republic, helping students compare how different forms express ideas and shape readers’ understanding.

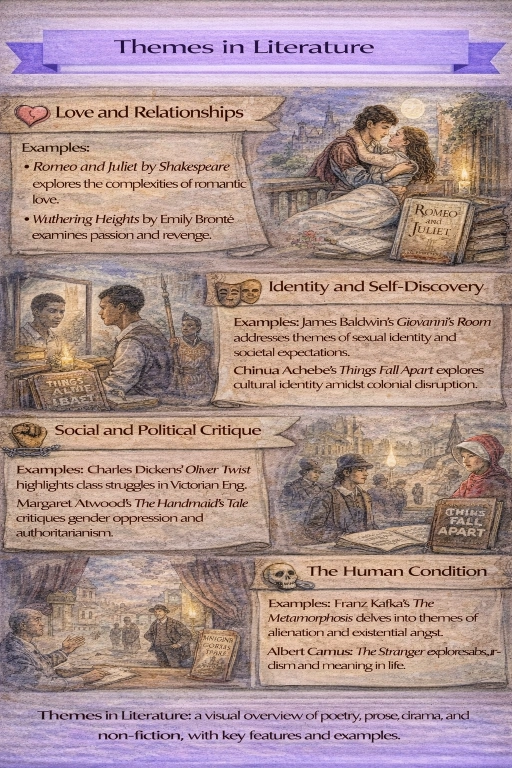

Themes in Literature

Love and Relationships

- Examples:

- Romeo and Juliet by Shakespeare explores the complexities of romantic love.

- Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë examines passion and revenge.

- Examples:

Identity and Self-Discovery

- Examples:

- James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room addresses themes of sexual identity and societal expectations.

- Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart explores cultural identity amidst colonial disruption.

- Examples:

Social and Political Critique

- Examples:

- Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist highlights class struggles in Victorian England.

- Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale critiques gender oppression and authoritarianism.

- Examples:

The Human Condition

- Examples:

- Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis delves into themes of alienation and existential angst.

- Albert Camus’ The Stranger explores absurdism and meaning in life.

- Examples:

A hand-painted, parchment-style infographic headed “Themes in Literature.” It is divided into four illustrated sections: Love and Relationships (with Romeo and Juliet and Wuthering Heights), Identity and Self-Discovery (with James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room and Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart), Social and Political Critique (with Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist and Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale), and The Human Condition (with Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis and Albert Camus’ The Stranger). Each section includes a small icon (heart, theatre masks, raised fist/chain motif, and skull) and a matching scene (readers, city or historical backdrops, and book stacks) to visually reinforce the theme.

Historical Periods of Literature

Classical Literature

- Encompasses works from ancient Greece and Rome, emphasizing epic poetry, drama, and philosophy.

- Key Figures: Homer, Virgil, Sophocles, Plato.

Medieval Literature

- Reflects religious and chivalric themes, with notable works like Dante’s Divine Comedy and Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales.

Renaissance Literature

- Marked by humanism, exploration, and innovation in form and content.

- Key Figures: William Shakespeare, Miguel de Cervantes, Christopher Marlowe.

Enlightenment and Romanticism

- The Enlightenment emphasized reason and progress (e.g., Voltaire), while Romanticism celebrated emotion and nature (e.g., Wordsworth, Keats).

Modern and Postmodern Literature

- Modernism broke traditional conventions (e.g., James Joyce’s Ulysses), while Postmodernism questioned narrative structures and reality (e.g., Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow).

Contemporary Literature

Contemporary literature reflects diverse voices and global issues, often addressing themes of identity, technology, and social justice.

- Key Trends:

- Multicultural narratives (e.g., Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah).

- Climate fiction addressing environmental issues (e.g., Margaret Atwood’s Oryx and Crake).

- Digital literature leveraging multimedia formats.

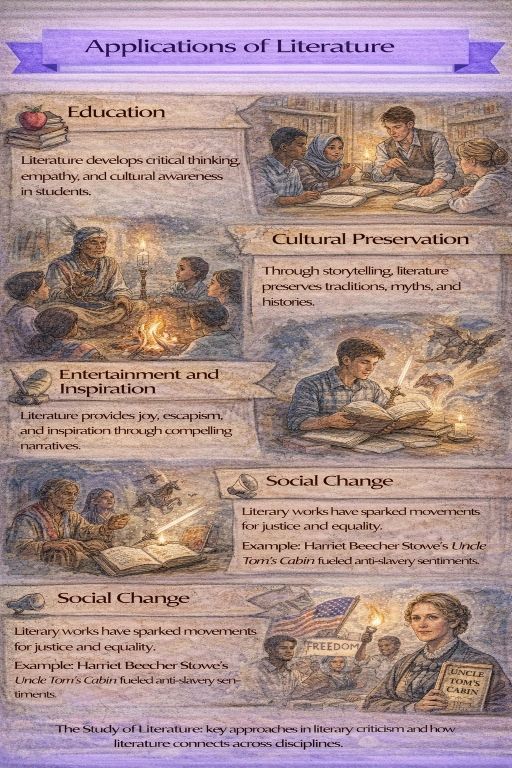

Applications of Literature in Society

Education

- Literature develops critical thinking, empathy, and cultural awareness in students.

Cultural Preservation

- Through storytelling, literature preserves traditions, myths, and histories.

Entertainment and Inspiration

- Literature provides joy, escapism, and inspiration through compelling narratives.

Social Change

- Literary works have sparked movements for justice and equality.

- Example: Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin fueled anti-slavery sentiments.

A hand-painted, textured infographic with a purple title ribbon reading “Applications of Literature.” Four main illustrated panels explain: Education (students learning together with books), Cultural Preservation (an elder telling stories to children by fire/candlelight), Entertainment and Inspiration (a reader illuminated by candlelight with imaginative figures in the background), and Social Change (activism imagery and a portrait-like figure holding a book labeled Uncle Tom’s Cabin, paired with text about justice and equality). The “Social Change” section appears twice, and there is a small footer line referencing “The Study of Literature.”

Challenges in Literature

Translation and Interpretation

- Translating literature across languages can alter its nuances.

Censorship

- Literary works are often banned for challenging social or political norms.

Relevance in a Digital Age

- Ensuring literature remains relevant in a world dominated by digital media.

Why Study Literature

Understanding Human Experience Across Time and Cultures

Exploring Language, Imagination, and Creativity

Analyzing Social, Political, and Ethical Themes

Recognizing Diverse Voices and Cultural Narratives

Preparing for Academic Excellence and Lifelong Learning

Literature: Conclusion

Literature is an enduring art form that captures the depth and breadth of human experience. From ancient epics to contemporary novels, it reflects our struggles, dreams, and realities. The study of literature enriches our understanding of ourselves and the world, fostering creativity, empathy, and critical thought. As we continue to tell stories, literature will remain a vital force in shaping cultures, inspiring change, and connecting generations.