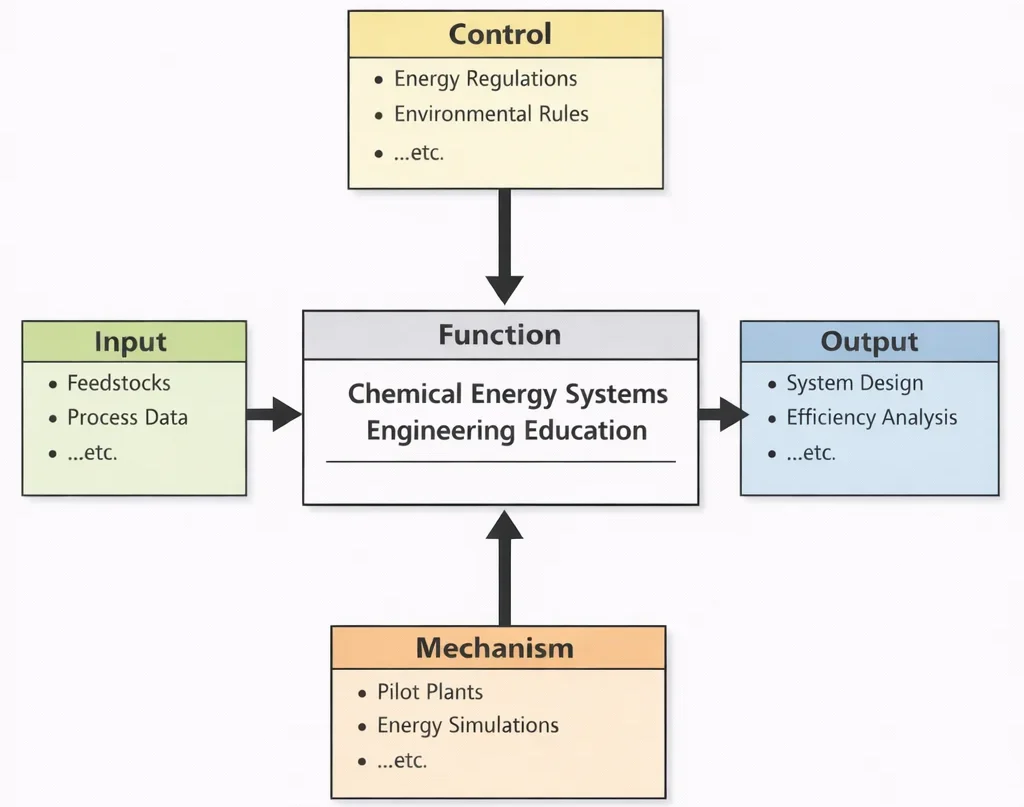

Chemical Energy Systems Engineering Education, viewed through this diagram, teaches students to connect chemistry with real energy performance. The Inputs ground learning in what the world actually provides—feedstocks with different compositions and constraints, and process data that reveal how systems behave under load. The Controls ensure that “good engineering” is not defined only by technical success, but also by legality and responsibility: designs must meet regulations, reduce pollution, and account for environmental consequences. The Mechanisms—pilot-scale experimentation and simulation—train students to think like system architects: to predict outcomes, verify assumptions, troubleshoot deviations, and optimize configurations before committing to full-scale implementation. The Outputs are graduates who can design energy systems and quantify their efficiency with clarity, balancing performance, cost, and sustainability in technologies such as fuel processing, hydrogen production, energy storage pathways, and low-emission conversion processes.

Chemical Energy Systems Engineering plays a crucial role in addressing the global demand for clean, efficient, and sustainable energy solutions. At its foundation lies a strong understanding of Chemical Engineering, which provides the principles of thermodynamics, fluid mechanics, and reactor design that underpin energy conversion systems. In particular, the integration of biological pathways through Biochemical Engineering supports the development of biofuels and biogas technologies.

The design and optimization of catalytic converters, fuel cells, and combustion processes heavily rely on knowledge from Chemical Catalysis and Reaction Engineering. To ensure durability and efficiency, material selection and innovation from Chemical Materials Engineering are critical, especially in high-temperature or corrosive environments. The overall design of energy plants draws upon system-wide principles from Chemical Process Engineering, ensuring coherent operation of complex unit processes.

Simulations are indispensable in optimizing fuel flow, heat exchange, and emissions control, making Computational Chemical Engineering vital for reducing trial-and-error experimentation. Energy systems also extend into sectors like Food and Beverage Engineering, where steam and thermal energy are key utilities. Recent advancements in Nanotechnology in Chemical Engineering further enhance catalytic surfaces, membranes, and energy storage materials.

Designing components for batteries, supercapacitors, and hydrogen tanks often depends on insights from Polymer and Plastics Engineering. Large-scale facilities for energy production must be integrated into safe structures planned by Civil Engineering experts, while coordination with Construction Management ensures smooth execution of engineering designs. Moreover, issues like thermal expansion, vibration, and seismic resistance are managed with expertise from Earthquake and Disaster Engineering.

Proper siting and soil stability assessments rely on Geotechnical Engineering, while mechanical frameworks for turbines and generators fall under Structural Engineering. Transporting fuels and managing logistics call for principles from Transportation Engineering and infrastructure planning from Urban and Regional Planning. Hydroelectric power plants and cooling systems intersect with Water Resources Engineering.

Instrumentation, control, and power electronics form the backbone of modern energy systems. The overall integration is supported by Electrical and Electronic Engineering. Monitoring combustion efficiency or emissions with precision often adapts tools from Biomedical Electronics. Secure transmission of sensor data and command signals is facilitated by Communication Engineering, while automation logic is designed using Control Systems Engineering.

From voltage regulators to ignition systems, Electronics Engineering contributes essential components. Smart grids and distributed energy systems rely heavily on microcontrollers and hardware platforms designed in Embedded Systems and Microelectronics. To meet safety, compliance, and efficiency targets, the use of calibrated sensors and feedback loops provided by Instrumentation and Measurement is indispensable in Chemical Energy Systems Engineering.

A digital illustration of a modern chemical-energy facility interior. On the left, a large illuminated reactor vessel glows cyan and is overlaid with floating icons (molecules, droplets, hexagons) suggesting reaction pathways and process chemistry. To the right, a technician/engineer in a white lab coat stands at an angled, glass-like console reviewing live system readouts. Behind them are rows of metallic tanks and instrumentation, while large wall panels show an atom emblem, the heading “Chemical Energy Systems,” and dashboard-style graphs that imply performance, efficiency, and operational control.

Chemical Energy Systems Engineering – Invisible FAQ

- How does chemical energy systems engineering differ from traditional power engineering?

- Chemical energy systems engineering focuses on energy storage and conversion using chemical and electrochemical processes such as fuel cells, batteries and hydrogen technologies. Traditional power engineering is centred on mechanical and electrical systems such as turbines, generators and transmission networks. Chemical energy systems bridge materials science, electrochemistry and process engineering to enable flexible, low-carbon energy solutions.

- Why are fuel cells considered a key technology for the hydrogen economy?

- Fuel cells convert the chemical energy of hydrogen directly into electricity with high efficiency and very low local emissions, typically producing only water and heat. This makes them well suited for applications where clean, quiet and efficient power is needed, from vehicles and backup power to distributed generation, and positions them as a core technology in hydrogen-based energy systems.

- What are the main engineering challenges in scaling up hydrogen production from renewable electricity?

- Challenges include improving electrolyser efficiency and lifetime, reducing capital costs, integrating electrolysers with variable renewable power, and developing infrastructure for compression, storage and distribution. Engineers must also address system-level issues such as matching production profiles to demand, managing heat and oxygen by-products, and ensuring overall safety.

- How do batteries and fuel cells play complementary roles in energy systems?

- Batteries are typically used for short- to medium-duration storage and rapid response, making them ideal for grid stabilisation, consumer electronics and electric vehicles. Fuel cells, combined with hydrogen storage, are better suited for longer-duration energy storage and extended-range applications. Together, they offer a portfolio of options for balancing supply and demand in low-carbon energy systems.

- What thermodynamic concepts are most relevant in chemical energy systems engineering?

- Key concepts include Gibbs free energy, which sets the theoretical maximum electrical work from an electrochemical cell; enthalpy and entropy changes, which govern heat effects; and efficiency limits derived from the first and second laws of thermodynamics. These concepts guide the design of fuel cells, batteries and hydrogen processes to minimise irreversibilities and energy losses.

- How do electrochemical reaction kinetics influence the design of fuel cells and batteries?

- Electrochemical kinetics determine how quickly charge-transfer reactions proceed at electrodes. Slow kinetics lead to activation overpotentials and reduced efficiency. Engineers use catalysts, increased surface area, optimised electrode microstructure and tailored electrolytes to enhance reaction rates and reduce losses, while balancing cost and durability.

- What safety issues are critical in hydrogen storage and handling?

- Hydrogen has a wide flammability range, low ignition energy and high diffusivity, so safety design must address leak detection, ventilation, material compatibility (to avoid embrittlement), and appropriate pressure and temperature controls. Codes, standards and risk assessments are central to ensuring safe deployment in vehicles, buildings and industrial facilities.

- How can life-cycle assessment be used to evaluate chemical energy technologies?

- Life-cycle assessment (LCA) estimates environmental impacts from raw material extraction through manufacturing, operation and end-of-life. For batteries, fuel cells and hydrogen systems, LCA helps compare different chemistries, production routes and recycling strategies, revealing trade-offs between carbon footprint, resource use and pollution, and informing sustainable design choices.

- What role do power-to-X concepts play in chemical energy systems engineering?

- Power-to-X concepts convert surplus renewable electricity into chemical energy carriers, such as hydrogen, synthetic fuels or chemicals. Chemical energy systems engineers design the electrolysers, synthesis reactors, separation units and integration strategies needed to turn intermittent electricity into storable, transportable products that can decarbonise sectors like industry, transport and heating.

- Which skills are important for students interested in chemical energy systems engineering?

- Students benefit from strong foundations in thermodynamics, transport phenomena, electrochemistry, reaction engineering and materials science, alongside familiarity with process simulation, data analysis and energy systems modelling. An understanding of sustainability metrics, policy drivers and techno-economic assessment is also valuable for real-world decision-making.

- Chemical Engineering topics:

- Chemical Engineering – Overview

- Chemical Process Engineering

- Chemical Catalysis & Reaction Engineering

- Chemical Materials Engineering

- Chemical Energy Systems Engineering

- Polymer & Plastics Engineering

- Nanotechnology in Chemical Engineering

- Biochemical Engineering

- Food & Beverage Engineering

- Computational Chemical Engineering

Table of Contents

Core Concepts in Chemical Energy Systems Engineering

Energy Conversion and Efficiency

- Definition:

Transforming raw energy sources into usable forms of energy with minimal losses. - Key Processes:

- Combustion Systems: Conversion of fossil fuels into thermal and mechanical energy.

- Electrochemical Processes: Direct conversion of chemical energy into electricity (e.g., fuel cells).

- Thermochemical Processes: Heat-driven chemical reactions for fuel production.

- Efficiency Optimization:

- Reducing energy losses through advanced heat recovery, process integration, and waste minimization.

Fossil Fuel Processing and Optimization

- Definition:

Refining and improving the use of non-renewable energy sources such as coal, oil, and natural gas. - Processes:

- Petroleum Refining: Fractional distillation and catalytic cracking.

- Gas-to-Liquid (GTL): Converting natural gas into liquid fuels.

- Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage (CCUS): Reducing carbon emissions.

Renewable Energy Technologies

- Definition:

Harnessing and optimizing energy from naturally replenishing sources. - Technologies:

- Bioenergy: Production of biofuels (bioethanol, biodiesel) from biomass.

- Solar Energy: Photovoltaics (PV) and solar thermal systems.

- Wind and Hydropower: Integration with chemical storage systems.

Hydrogen Production and Storage

- Definition:

Producing and storing hydrogen as a clean energy carrier. - Hydrogen Production Methods:

- Steam Methane Reforming (SMR): Current dominant method using natural gas.

- Electrolysis: Splitting water using electricity from renewable sources.

- Photoelectrochemical (PEC) Water Splitting: Using sunlight for hydrogen production.

- Hydrogen Storage:

- Compressed gas, liquid hydrogen, and metal hydrides for safe and efficient storage.

Fuel Cells and Electrochemical Energy Systems

- Definition:

Devices that convert chemical energy directly into electricity through electrochemical reactions. - Types of Fuel Cells:

- Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells (PEMFC): Used in transportation and portable devices.

- Solid Oxide Fuel Cells (SOFC): High-efficiency systems for stationary power.

- Alkaline Fuel Cells (AFC): Historically used in space missions.

Energy Storage Systems

- Definition:

Technologies for storing energy for later use to balance supply and demand. - Technologies:

- Batteries: Lithium-ion, flow batteries, and solid-state batteries.

- Supercapacitors: High-power, short-term energy storage.

- Thermal Energy Storage: Molten salts and phase-change materials for solar energy storage.

Nuclear Energy Systems

- Definition:

Harnessing nuclear reactions to generate energy. - Technologies:

- Fission Reactors: Traditional reactors using uranium and plutonium.

- Fusion Reactors: Experimental reactors mimicking the sun’s energy production.

- Small Modular Reactors (SMRs): Compact and safer nuclear designs.

Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage (CCUS)

- Definition:

Technologies aimed at capturing and storing or reusing CO₂ emissions from industrial processes. - Processes:

- Post-Combustion Capture: Removing CO₂ from flue gases.

- Pre-Combustion Capture: Capturing CO₂ before fuel combustion.

- Carbon Utilization: Converting CO₂ into chemicals, fuels, or building materials.

Key Applications of Chemical Energy Systems Engineering

Power Generation

- Fossil Fuel Power Plants:

- Enhancing combustion efficiency using advanced thermodynamic cycles, such as supercritical CO2 cycles and combined heat and power (CHP) systems.

- Reducing emissions through integrated carbon capture, flue gas scrubbing, and catalytic converters to meet increasingly strict environmental standards.

- Co-firing biomass with coal to lower the carbon intensity of power generation and transition toward cleaner fuels.

- Renewable Energy Integration:

- Designing hybrid power systems that combine photovoltaic solar, wind turbines, and thermal energy with battery and chemical storage systems for consistent energy delivery.

- Developing smart grid algorithms that match real-time supply with fluctuating demand using predictive analytics and demand-side management.

- Linking solar thermal plants with molten salt storage to extend renewable energy availability beyond daylight hours.

Sustainable Fuel Production

- Biofuels:

- Engineering biochemical pathways to convert lignocellulosic biomass into second-generation bioethanol and biobutanol, reducing competition with food crops.

- Optimizing algal biofuel production by improving lipid yield and harvesting techniques to support scalable alternatives to petroleum diesel.

- Utilizing anaerobic digestion for biogas generation from agricultural and municipal waste, contributing to decentralized energy solutions.

- Synthetic Fuels:

- Producing synthetic natural gas (SNG) and Fischer-Tropsch fuels by capturing and converting CO2 with green hydrogen, thus recycling carbon into useful forms.

- Advancing Power-to-Liquids (PtL) and Power-to-Gas (PtG) systems to store excess renewable electricity as synthetic hydrocarbons or methane.

- Developing catalysts that improve efficiency and selectivity in gas-to-liquid (GTL) and coal-to-liquid (CTL) conversion processes.

Hydrogen Economy

- Fuel Cell Vehicles:

- Deploying hydrogen-powered buses, trucks, and trains that emit only water, reducing greenhouse gas emissions from transportation.

- Establishing hydrogen refueling infrastructure to support large-scale adoption of fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs).

- Improving fuel cell durability, cost, and energy density for competitive performance against battery electric vehicles.

- Industrial Hydrogen:

- Scaling up green hydrogen production via electrolysis powered by wind, solar, or hydro energy, replacing fossil-fuel-based hydrogen (grey and blue hydrogen).

- Using hydrogen in high-temperature industrial applications such as steelmaking, glass production, and cement manufacturing to drastically cut carbon emissions.

- Integrating hydrogen in ammonia synthesis for fertilizers and maritime fuel through the Haber-Bosch process powered by renewables.

- Explore global hydrogen initiatives on Hydrogen Council.

Grid Energy Storage

- Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS):

- Utilizing lithium-ion, flow batteries, and sodium-sulfur technologies to balance electricity supply and demand.

- Storing excess renewable energy during low demand periods for release during peak consumption, ensuring grid reliability.

- Applying thermal and chemical battery designs to extend operational life and reduce environmental impact.

- Compressed Air Energy Storage (CAES):

- Harnessing off-peak electricity to compress and store air in geological formations or tanks for later electricity generation.

- Combining CAES with heat recovery systems to improve round-trip efficiency.

- Emerging CAES installations across Europe and the U.S. are paving the way for long-duration storage. See examples at Energy Storage Association.

Carbon Management

- Direct Air Capture (DAC):

- Deploying engineered chemical sorbents to capture atmospheric CO2, aiding in reversing legacy emissions.

- Utilizing captured carbon for synthetic fuel production, carbonation of concrete, or underground sequestration.

- Innovating modular DAC units for decentralized carbon capture, especially in remote or low-density regions.

- Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR):

- Injecting CO2 into mature oil fields to extract additional crude while storing the gas underground.

- Improving economic feasibility of carbon capture through co-benefits from increased oil yield.

- Transitioning EOR from fossil-centric to net-zero processes by ensuring permanent CO2 retention.

Emerging Technologies in Chemical Energy Systems Engineering

Green Hydrogen Production

- Technologies:

- PEM Electrolysis: Proton Exchange Membrane (PEM) electrolysis allows for the efficient splitting of water into hydrogen and oxygen using renewable electricity such as wind or solar. It offers fast response times, compact design, and high purity output, making it ideal for integrating with intermittent renewable energy sources.

- Biophotolysis: This technique involves using photosynthetic organisms such as microalgae and cyanobacteria to produce hydrogen directly from sunlight and water. As a biological pathway, it is still under research but shows promise for producing green hydrogen with low energy input and minimal environmental impact.

- Applications and Impact:

- Green hydrogen is being adopted in sectors such as steel manufacturing, heavy transport, and ammonia production to reduce carbon emissions.

- Hydrogen storage offers an efficient method for storing excess renewable electricity, thereby stabilizing the grid.

- Learn more about real-world hydrogen projects on the IEA Global Hydrogen Review.

Solid-State Batteries

- Advantages:

- Unlike traditional lithium-ion batteries that use liquid electrolytes, solid-state batteries use solid electrolytes, which are safer and less flammable.

- They offer significantly higher energy density, allowing for longer driving ranges in electric vehicles (EVs).

- These batteries exhibit lower degradation over time, increasing lifespan and reducing waste.

- Emerging Research and Commercialization:

- Companies such as Toyota and QuantumScape are investing heavily in solid-state battery technology, aiming for commercial EV deployment by the late 2020s.

Artificial Photosynthesis

- Definition and Principles:

- Artificial photosynthesis aims to mimic the natural process of converting sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide into energy-rich compounds such as hydrogen or methanol.

- It often uses semiconductors, catalysts, and light-absorbing molecules to drive the conversion of solar energy into chemical energy.

- Potential Applications:

- Produces solar fuels directly, eliminating the need for intermediate steps like electricity generation.

- Helps reduce CO₂ levels while producing storable energy carriers, aiding decarbonization efforts.

- Explore artificial photosynthesis advances on the Solar Fuels Hub.

Molten Salt Reactors (MSRs)

- Advantages and Safety:

- MSRs use molten fluoride or chloride salts as the primary coolant and sometimes as the fuel carrier, allowing for very high operating temperatures with passive safety features.

- They offer inherent safety through low-pressure operation and the ability to drain fuel into secure holding tanks during emergencies.

- These reactors produce less nuclear waste and can operate on thorium, a more abundant and proliferation-resistant fuel.

- Innovation and Potential:

- Startups and research centers globally are exploring MSRs as the next generation of nuclear energy—cleaner, safer, and more flexible.

- MSRs can be paired with industrial heat applications and hydrogen production for increased efficiency.

Microbial Fuel Cells (MFCs)

- Definition and Function:

- MFCs generate electricity by using bacteria that break down organic matter in wastewater or biomass, releasing electrons that flow through an external circuit.

- These bioelectrochemical systems operate at ambient conditions and serve the dual purpose of waste treatment and renewable electricity generation.

- Real-World Use and Research:

- Research is ongoing into improving electron transfer efficiency and scaling up MFCs for use in rural electrification, remote sensors, and sustainable sanitation systems.

- Future designs may integrate with industrial wastewater facilities, turning liabilities into energy assets.

Challenges in Chemical Energy Systems Engineering

Scalability of Sustainable Technologies

- One of the foremost challenges in chemical energy systems engineering is scaling up technologies such as green hydrogen production, advanced fuel cells, and carbon capture and storage (CCS). While these technologies have shown promise in laboratory and pilot settings, replicating their performance at industrial scale remains complex and resource-intensive.

- Scalability involves addressing supply chain limitations for rare materials, ensuring consistent process yields, and designing large-scale systems that maintain safety, durability, and economic feasibility.

- Green hydrogen, for instance, requires electrolyzers that can operate efficiently on fluctuating renewable energy inputs, and the mass production of these systems is currently limited.

- To explore the current progress in scaling hydrogen technologies, visit Hydrogen Shot by the U.S. Department of Energy.

Energy Efficiency

- Energy efficiency is a core metric in assessing the viability of chemical energy systems. From electrolysis to battery storage to thermal power generation, energy losses during conversion, transmission, and storage must be minimized to optimize system performance.

- Technological inefficiencies often arise from heat loss, resistance in materials, suboptimal catalysts, or inadequate integration between subsystems.

- Chemical engineers must develop new materials, smarter system designs, and novel thermodynamic cycles that maximize output per unit of energy input while minimizing environmental impact.

- Integrating AI-based process optimization and real-time monitoring may provide next-generation solutions to this challenge.

Infrastructure for Hydrogen and Renewables

- While producing hydrogen and renewable electricity is becoming increasingly feasible, the supporting infrastructure is critically underdeveloped. Challenges include building pipelines for hydrogen transport, high-capacity grid interconnects, hydrogen refueling stations, and large-scale storage solutions such as compressed gas tanks or liquid hydrogen systems.

- Moreover, retrofitting existing fossil-fuel infrastructure for compatibility with renewables is not always possible or economically viable.

- Ensuring material compatibility, especially to prevent hydrogen embrittlement in pipelines, is essential.

- For deeper insight into global hydrogen infrastructure projects, see The Future of Hydrogen by IEA.

Cost Reduction

- The financial barrier is one of the primary hurdles in the mass adoption of clean energy systems. Green hydrogen is still significantly more expensive than hydrogen produced from natural gas (gray hydrogen), and large-scale batteries or fuel cells require rare materials such as lithium, cobalt, or platinum, which are costly and geopolitically constrained.

- Cost-effective manufacturing techniques, economies of scale, and investment in recycling and alternative materials are essential strategies to lower costs across the energy chain.

- Government subsidies, carbon pricing, and public-private partnerships also play a crucial role in making these technologies commercially competitive with fossil fuels.

- Developing local supply chains and reducing reliance on critical imports are additional economic priorities.

Regulatory and Safety Concerns

- With the introduction of novel energy systems come new safety hazards and regulatory complexities. Hydrogen, for instance, is highly flammable and requires strict handling procedures. Similarly, fuel cells and batteries can pose risks of thermal runaway or leakage under improper conditions.

- Standardizing testing, certification, and operational protocols is essential to ensure public trust and safe deployment.

- Governments and international bodies must collaborate to update existing safety codes and develop new regulations that are aligned with emerging technologies while not stifling innovation.

- Proactive engagement with communities and transparent risk communication will help in the adoption of new technologies.

Future Directions in Chemical Energy Systems Engineering

Hydrogen-Powered Economy:

- Widespread hydrogen use across transport, industry, and power sectors.

Net-Zero Energy Systems:

- Designing carbon-neutral industrial processes and power generation.

Circular Carbon Economy:

- Capturing and recycling CO₂ into fuels and chemicals.

Decentralized Energy Grids:

- Distributed renewable energy production with local storage.

Fusion Energy Commercialization:

- Developing sustainable fusion reactors for limitless clean energy.

Why Study Chemical Energy Systems Engineering

Producing and Storing Energy

This field explores how chemical processes generate and store energy. Students study batteries, fuel cells, and combustion systems. They learn to improve performance and sustainability in energy applications.

Thermodynamics and Electrochemistry

Students apply principles of energy conservation, heat transfer, and electrochemical reactions. This helps them design efficient and safe energy systems. These foundations are essential for modern energy technology.

Renewable and Alternative Energy Sources

The course emphasizes biofuels, hydrogen, and solar-to-chemical conversion. Students learn to assess environmental impact and resource availability. This prepares them to lead in the transition to clean energy.

System Integration and Lifecycle Analysis

Students study how to integrate chemical energy systems into larger energy grids. They perform lifecycle assessments to evaluate sustainability. These insights guide policy, design, and operational decisions.

Careers in Energy Innovation

Chemical energy engineers are in demand in utilities, research labs, and technology startups. Students contribute to solving global energy challenges. The field offers impactful and forward-looking career opportunities.

Chemical Energy Systems Engineering: Conclusion

Chemical Energy Systems Engineering is increasingly recognized as a cornerstone in the global push toward energy sustainability, security, and innovation. This interdisciplinary field blends chemical engineering principles with advanced energy systems to design, analyze, and optimize processes for generating, converting, storing, and utilizing energy. Its significance lies not just in maximizing efficiency, but also in ensuring that energy technologies remain environmentally responsible and economically scalable.

Transforming Energy Infrastructure

One of the field’s most transformative contributions is the integration of renewable resources into existing energy infrastructures. Engineers are developing methods to store intermittent energy from solar and wind through chemical carriers like hydrogen and ammonia, thus ensuring grid stability. By advancing electrochemical systems such as redox flow batteries and fuel cells, Chemical Energy Systems Engineering enables scalable energy storage critical for future smart grids. Learn more about hydrogen storage innovations from the U.S. Department of Energy.

Decarbonization through Process Innovation

To tackle the climate crisis, the discipline supports the design of integrated processes that capture and utilize CO2. Engineers are optimizing chemical loops and gasification systems that not only extract energy efficiently but also recycle waste gases into useful products. These closed-loop systems are helping industries significantly reduce their carbon footprint while generating economic value from emissions.

Hydrogen Economy and Fuel Cells

Fuel cells and hydrogen-based technologies are central to the clean energy landscape. Chemical energy engineers are at the forefront of scaling up proton exchange membrane (PEM) and solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs) for both stationary and mobile applications. Research is also directed at improving hydrogen production via water electrolysis using renewable energy sources. The emergence of the hydrogen economy opens opportunities for deep decarbonization across sectors, including transportation, manufacturing, and heavy industry. For more on this, explore The Future of Hydrogen by the IEA.

Integrated Energy Systems and Circular Economies

Chemical energy systems engineers are also focusing on circular economy approaches, where waste heat, CO2, and biomass are redirected into productive cycles. Innovations in thermochemical and electrochemical energy conversion allow industries to recover and repurpose energy more effectively. This results in synergistic systems where by-products of one process become valuable inputs for another, improving both environmental and economic outcomes.

Digital Tools and Smart Optimization

Emerging tools like process simulation, digital twins, and machine learning are revolutionizing how energy systems are designed and operated. Engineers can now predict performance, identify inefficiencies, and simulate thousands of scenarios to design optimal systems under varying demand and climate conditions. These digital capabilities ensure that energy production and utilization remain responsive, resilient, and data-informed.

In summary, Chemical Energy Systems Engineering is central to building a sustainable energy future. By uniting advanced materials science, reaction engineering, thermodynamics, and systems design, it enables a seamless transition from fossil-dependent systems to low-carbon, renewable, and circular models. Its continued evolution will empower the next generation of engineers to create scalable, secure, and sustainable energy solutions that meet the demands of a growing global population while safeguarding planetary health.

Chemical Energy Systems Engineering – Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. How is chemical energy systems engineering linked to the energy transition?

Chemical energy systems engineering focuses on technologies such as fuel cells, advanced batteries and hydrogen production that enable cleaner, more efficient use of energy. By improving how we store and convert energy, it helps integrate renewables, reduce greenhouse gas emissions and gradually move away from fossil-fuel-dependent systems.

2. Why are fuel cells often described as more efficient than combustion engines?

Fuel cells convert chemical energy directly into electrical energy through electrochemical reactions, avoiding the intermediate step of generating heat and mechanical work. This direct conversion can achieve higher efficiencies than combustion engines, which are constrained by thermodynamic cycle limits and mechanical losses.

3. What makes different types of fuel cells suitable for different applications?

Each fuel cell type has its own operating temperature, electrolyte and fuel flexibility. For example, PEM fuel cells operate at low temperatures and respond quickly, making them suitable for vehicles, while SOFCs operate at high temperatures, allowing them to use a wider range of fuels and achieve high efficiencies in stationary power systems. Matching these characteristics to real-world needs guides technology selection.

4. How do improvements in battery technology affect everyday life?

Better batteries offer higher energy density, faster charging and longer lifetimes. This translates into longer ranges for electric vehicles, more capable portable electronics, and more robust grid-scale storage to support renewable energy. As costs fall and performance rises, batteries increasingly shape how we move, communicate and power our homes.

5. Why is hydrogen viewed as an important energy carrier rather than a primary energy source?

Hydrogen does not typically occur in pure form and must be produced from other energy sources, such as electricity or natural gas. It is therefore an energy carrier: it stores energy that was originally supplied by another source. Its value lies in being easy to convert back to electricity or heat and in its potential to decarbonise hard-to-electrify sectors when produced from low-carbon sources.

6. What are the main engineering challenges in storing hydrogen?

Hydrogen has a low volumetric energy density, so it must be compressed, liquefied or stored in materials to hold useful amounts. Each option introduces challenges related to pressure, temperature, material compatibility and cost. Engineers work to design safe, efficient tanks and storage systems that can be used in vehicles, refuelling stations and large-scale energy storage.

7. How does thermodynamics help us judge the efficiency of energy conversion devices?

Thermodynamics provides the theoretical limits for how much useful work can be obtained from a given chemical or thermal process. By comparing actual device performance with these limits, engineers can identify where losses occur, such as in overpotentials, heat generation or resistive losses, and then target design improvements to reduce these inefficiencies.

8. In what ways do chemical energy systems benefit the environment?

When designed well and supplied with low-carbon inputs, chemical energy systems can reduce greenhouse gas emissions, decrease air pollutants like NOx and particulates, and support greater use of renewable energy. Examples include zero tailpipe emissions from hydrogen fuel cell vehicles and battery storage that allows excess solar or wind energy to be used later instead of curtailment.

9. Why are electrochemical reactions central to many modern energy technologies?

Electrochemical reactions enable direct interconversion between chemical and electrical energy, which is the basis of batteries, supercapacitors and fuel cells. This avoids intermediate mechanical stages and often offers higher efficiency, better controllability and modular designs compared with conventional combustion-based technologies.

10. How does integrating renewables with chemical energy systems improve grid reliability?

Renewable sources like solar and wind are variable. By coupling them with batteries, hydrogen production or other chemical storage systems, surplus electricity can be stored when generation is high and released when demand increases or the sun and wind are not available. This smoothing effect helps maintain a stable and reliable power supply.

Chemical Energy Systems Engineering: Review Questions and Answers:

-

What is chemical energy systems engineering, and how does it support sustainable energy transitions?

Answer: Chemical energy systems engineering focuses on using chemical and electrochemical processes to convert, store and deliver energy efficiently. It underpins sustainable energy transitions by enabling technologies such as fuel cells, advanced batteries and hydrogen production routes that can operate with low emissions, integrate renewable power and reduce dependence on fossil fuels across transport, industry and power sectors. -

How do fuel cells generate electricity, and why are they attractive alternatives to combustion-based power sources?

Answer: Fuel cells generate electricity through electrochemical reactions, typically combining hydrogen fuel with oxygen from air at separate electrodes. Electrons flow through an external circuit, providing useful electrical power, while water and heat are produced as by-products. Because fuel cells bypass the heat and mechanical work stages found in combustion engines, they can achieve higher efficiencies and much lower pollutant emissions, making them attractive for clean power and transport applications. -

What are the main types of fuel cells, and where are they commonly used?

Answer: Key fuel cell types include Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells (PEMFCs), Solid Oxide Fuel Cells (SOFCs) and Alkaline Fuel Cells (AFCs). PEMFCs operate at relatively low temperatures and respond quickly to load changes, making them well suited to vehicles and portable power. SOFCs operate at high temperatures, tolerate a wider range of fuels and are mainly used for stationary power and combined heat-and-power systems. AFCs have historically been used in space applications but are less common commercially due to their sensitivity to carbon dioxide in the feed. -

How are advances in battery technology shaping modern energy storage systems?

Answer: Advances in battery technology—such as improved lithium-ion chemistries, emerging solid-state batteries and new electrode materials—have increased energy density, reduced charging times and enhanced safety. These improvements enable longer-range electric vehicles, more compact consumer electronics and more effective grid-scale storage, helping to smooth out fluctuations in renewable generation and strengthen overall energy system resilience. -

What role does hydrogen play in chemical energy systems, and what challenges arise in producing and storing it?

Answer: Hydrogen acts as a flexible energy carrier that can be produced from various primary energy sources and later reconverted to electricity, heat or chemicals. It is central to fuel-cell systems and can serve as a feedstock in industry. However, challenges include developing low-carbon, cost-effective production routes (for example, electrolysis using renewable power), as well as designing safe, efficient storage and distribution systems to manage hydrogen’s low volumetric energy density and flammability. -

How do principles of thermodynamics guide the design of chemical energy systems?

Answer: Thermodynamics sets the theoretical limits for energy conversion efficiency and indicates how much of the chemical energy in a fuel can be converted into useful work. By applying the first and second laws of thermodynamics, engineers can compare technologies, estimate maximum efficiencies, identify major loss mechanisms and design fuel cells, batteries and hydrogen processes that minimise irreversibilities and waste heat. -

What environmental benefits can advanced chemical energy systems provide?

Answer: Advanced chemical energy systems can significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions and air pollutants when coupled with low-carbon energy sources. Fuel cells emit mainly water vapour at the point of use, while batteries enable higher penetration of renewables by storing surplus electricity instead of relying on fossil-fuel backup. Collectively, these systems help lower local air pollution, decrease reliance on finite fossil resources and move energy systems toward net-zero pathways. -

How do electrochemical reactions differ from conventional combustion reactions in energy applications?

Answer: Electrochemical reactions, as used in batteries and fuel cells, convert chemical energy directly into electrical energy through controlled redox processes at electrodes. Combustion reactions release chemical energy mainly as heat, which must then be converted into mechanical and electrical energy through thermodynamic cycles, often with larger losses. This direct conversion in electrochemical systems usually offers higher efficiency and more precise control than combustion-based technologies. -

What are key engineering considerations when designing reactors and devices for chemical energy applications?

Answer: Designing reactors and devices for energy applications requires attention to reaction kinetics, heat and mass transfer, electrode and catalyst design, material compatibility and durability. Engineers must ensure stable operation over many cycles, effective management of heat and by-products, and safe containment of reactive species. Scalability, manufacturability and cost are also crucial factors when moving from laboratory prototypes to full-scale systems. -

How does integrating renewable energy sources drive innovation in chemical energy systems?

Answer: The variable output of solar and wind power creates a strong demand for flexible storage and conversion technologies. This pushes innovation in batteries, hydrogen production, synthetic fuels and other chemical energy options that can absorb surplus electricity and release it when needed. By coupling renewables with chemical energy systems, engineers can design more reliable, low-carbon energy networks that match supply and demand across hours, days and even seasons.

Thought-Provoking Questions with Detailed and Elaborate Answers on Chemical Energy Systems Engineering

How does the principle of energy conservation apply to the design and operation of chemical energy systems?

- Answer: The principle of energy conservation, which states that energy cannot be created or destroyed but only transformed, is fundamental to chemical energy systems. In these systems, chemical energy is converted into usable forms such as electricity or heat. For instance, in a fuel cell, the chemical energy of hydrogen and oxygen is converted directly into electricity through electrochemical reactions. By understanding energy conservation, engineers design systems that minimize energy losses, improve efficiency, and optimize the balance between input energy and output energy.

What are the key trade-offs between efficiency and environmental impact when designing chemical energy systems?

- Answer: Higher efficiency often requires advanced materials and complex designs, which may increase the environmental impact during production. However, efficient systems reduce operational emissions and energy consumption. For example, a highly efficient hydrogen fuel cell may require rare materials like platinum but emits only water during operation. Engineers must weigh these trade-offs by considering lifecycle impacts, focusing on sustainable materials, and optimizing system performance to reduce environmental costs.

Why is hydrogen considered a promising energy carrier, and what are the challenges in its widespread adoption?

- Answer: Hydrogen is abundant, energy-dense, and produces no emissions when used in fuel cells, making it an attractive energy carrier. However, challenges include its production (often reliant on non-renewable energy sources), storage (low energy density per volume), and transportation (requires specialized infrastructure). Overcoming these barriers involves developing renewable production methods like electrolysis powered by solar or wind energy, designing lightweight and high-capacity storage systems, and building a global hydrogen distribution network.

How can advancements in nanotechnology improve the performance of catalysts used in chemical energy systems?

- Answer: Nanotechnology allows for the precise design of catalysts at the atomic level, enhancing their surface area and active site density. This increases reaction rates and selectivity, reducing the amount of catalyst material required. For example, nano-engineered catalysts can improve the efficiency of fuel cells by lowering the energy barrier for electrochemical reactions while reducing the dependence on expensive materials like platinum.

What role does thermodynamics play in determining the feasibility of chemical energy conversion processes?

- Answer: Thermodynamics governs the energy transformations in chemical processes, dictating which reactions are energetically favorable. Key concepts include enthalpy (heat exchange), entropy (disorder), and Gibbs free energy (energy available for work). Engineers use thermodynamic principles to evaluate whether a reaction can occur spontaneously and design processes that operate under optimal conditions to maximize energy conversion efficiency.

Why is energy storage a critical component of chemical energy systems, and what technologies are most promising for large-scale applications?

- Answer: Energy storage addresses the intermittent nature of renewable energy sources like solar and wind, ensuring a stable supply when demand fluctuates. Technologies like lithium-ion batteries, flow batteries, and hydrogen storage systems are promising. For large-scale applications, flow batteries offer scalability and long cycle life, while hydrogen storage provides high energy density and the ability to integrate with fuel cell systems for grid-scale energy solutions.

How can chemical energy systems contribute to the decarbonization of the transportation sector?

- Answer: Chemical energy systems like hydrogen fuel cells and advanced batteries enable zero-emission vehicles by replacing internal combustion engines. Hydrogen-powered vehicles emit only water, and battery-electric vehicles eliminate tailpipe emissions. Additionally, using renewable energy to produce hydrogen or charge batteries ensures the entire lifecycle of the vehicle is environmentally sustainable, accelerating the transition to clean transportation.

What challenges do engineers face in scaling up chemical reactors for industrial energy applications, and how can they address these challenges?

- Answer: Scaling up reactors requires maintaining reaction kinetics, efficient heat and mass transfer, and system stability under varying conditions. Engineers address these challenges by using computational models to simulate scaling effects, designing reactors with optimized geometries, and incorporating advanced materials that withstand industrial operating conditions. Pilot-scale testing is also crucial to validate designs before full-scale deployment.

How do electrochemical reactions in fuel cells differ from combustion reactions in conventional power generation?

- Answer: Electrochemical reactions in fuel cells directly convert chemical energy into electricity without combustion, resulting in higher efficiency and fewer emissions. Combustion reactions, on the other hand, involve burning fuel to produce heat, which is then converted into mechanical energy and electricity. This multi-step process is less efficient and produces greenhouse gases and other pollutants.

How can the concept of circular economy be applied to the development of sustainable chemical energy systems?

- Answer: A circular economy emphasizes minimizing waste and maximizing resource use. In chemical energy systems, this could involve recycling spent catalysts, reusing byproducts (e.g., heat recovery), and designing materials that are biodegradable or recyclable. For instance, waste heat from a hydrogen production plant can be used to generate electricity or heat nearby facilities, improving overall system efficiency and sustainability.

What are the potential risks associated with chemical energy systems, and how can these risks be mitigated?

- Answer: Risks include chemical leaks, fire hazards, and system inefficiencies. Mitigation strategies involve robust safety protocols, advanced monitoring systems, and using safer materials. For example, hydrogen systems require leak detection sensors and pressure relief devices to prevent explosions. Regular maintenance and adherence to industry standards further enhance safety and reliability.

How can artificial intelligence (AI) accelerate innovations in chemical energy systems engineering?

- Answer: AI can analyze vast datasets to optimize reaction conditions, predict system failures, and design new materials. For example, machine learning algorithms can identify patterns in catalyst performance data, guiding the development of more efficient catalysts. AI-driven simulations also enable rapid prototyping and testing of energy systems, reducing development time and costs.

These questions encourage exploration of key concepts, fostering critical thinking and innovation in the field of chemical energy systems engineering.