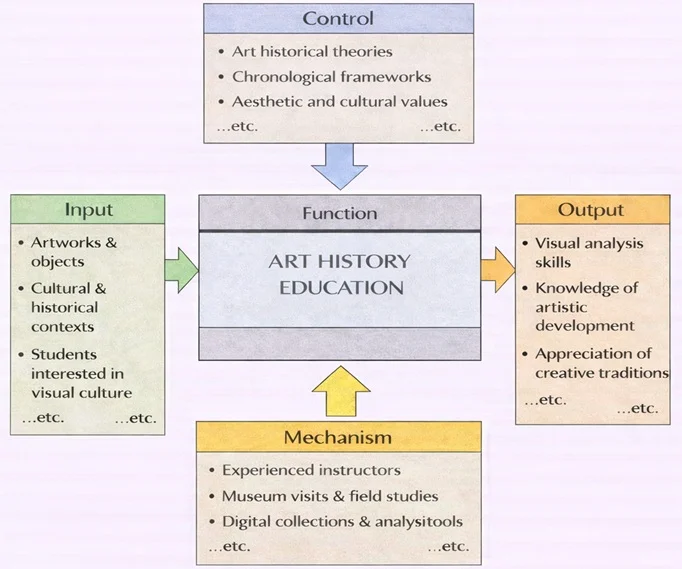

Art History Education is, in many ways, training the eye to think. Instead of treating paintings, sculptures, buildings, and everyday visual culture as silent objects, it teaches students to read them as historical evidence—full of choices, symbols, materials, and intentions. The key inputs include artworks and objects themselves, the cultural and historical contexts that surround them, and students who are drawn to images, design, and visual meaning. The learning process is guided by controls such as art historical theories, chronological frameworks, and aesthetic and cultural values, which help students place works in time, compare movements, and understand why different societies defined “beauty,” “craft,” or “genius” in different ways. The function is enabled by mechanisms: experienced instructors who model close looking and careful argument, museum visits and field studies that bring original works into view, and digital collections and analysis tools that expand access to global archives. When these elements align, the outputs are clear—stronger visual analysis skills, deeper knowledge of artistic development across periods and cultures, and a lasting appreciation for creative traditions that continue to shape how we see the world.

Art history is not merely the study of beautiful objects—it is a dynamic field that deciphers how cultures communicate their values, beliefs, and power structures through visual expression. From ancient iconography to modern installations, art reflects broader societal transformations. For example, the history of ideas helps illuminate the intellectual currents that inspired artistic revolutions such as the Renaissance, Romanticism, or Modernism. Artistic movements also intersect with the gender dynamics of their time, influencing who creates, views, and is represented in art.

To grasp how art fits within political frameworks, one must consider the history of political systems. Rulers and regimes have long commissioned art to express authority or ideology, whether through imperial statues, revolutionary posters, or civic monuments. Equally essential is the global evolution of political thought, which shaped aesthetic theories on freedom, identity, and public space.

Art also offers insights into the economic and social dimensions of society. The economic history of materials, patronage systems, and cultural industries reveals the shifting value of artistic labor. Exploring financial history helps explain how the art market evolved from aristocratic commissions to modern auction houses. These changes parallel developments in political economy and the theories of value and trade that underlie cultural commodification.

Art’s power to critique and reshape society is also visible in its relation to activism. The history of social movements includes visual protest traditions such as anti-war murals, feminist performance art, and anti-colonial graphics. These expressions frequently emerge in response to political shifts like electoral controversies or systemic inequality. In some contexts, art challenges the legitimacy of power as it did during upheavals studied in electoral history.

Artists have long been shaped by their education and mentorship. Exploring education history reveals how art academies, guilds, and informal workshops transmitted techniques and ideologies. Such knowledge was often controlled by elites or the state, tying it to constitutional reforms and Enlightenment ideals about civic participation and cultural refinement.

Art history also enriches our understanding of diplomacy and conflict. Paintings, architecture, and exhibitions have been deployed as instruments of cultural diplomacy, building bridges across political divides. Similarly, images produced during wartime, examined in the economic history of warfare, reveal how art has justified, documented, or resisted violence. The symbolic roles of visual media in peacebuilding and propaganda tie closely to diplomatic history and the personalities involved in shaping international image.

The development of aesthetics is also connected to broader environmental and material concerns. The environmental economic history shows how access to pigments, stone, or wood impacted styles and availability. These resources influenced the appearance of art and shaped regional distinctiveness, an important subject in the comparative study of civilizations through history.

Finally, studying art in context invites reflection on issues such as insurgency, ideological representation, and state symbolism. Aspects covered in guerrilla warfare and insurgency studies reveal how revolutionary imagery is central to movements that challenge the status quo. Political alliances, documented in the history of alliances, often rely on shared artistic symbols to express unity and legitimacy.

In sum, the study of art history opens a multidisciplinary window into human creativity, power, and belief. Drawing from fields like economic thought, economic diplomacy, and diplomatic personalities, art historians uncover the layers of meaning embedded in visual culture. Their work ensures that we not only admire what is seen but understand what it signifies.

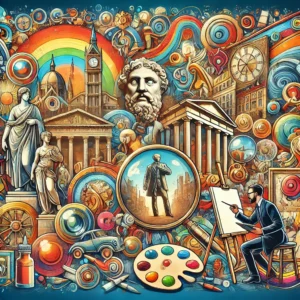

A vibrant, poster-style montage celebrates the sweep of art history. At the right, a seated artist paints at an easel beside a painter’s palette, tubes, and brushes—symbolizing making and learning by doing. Across the scene are classical marble statues and columned temples, a monumental carved head, and a central medallion with a standing figure, evoking ancient Greece and Rome and the Renaissance revival of antiquity. Clock towers, gears, and numerous clocks hint at art’s timeline and the role of technology and industrial change. Arches of rainbow color, swirling ornaments, and abstract shapes suggest modernism’s experimentation with form and color. Together these elements connect technique, patronage, and ideas across periods—antiquity, Renaissance, industrial modernity, and contemporary practice—capturing art as a continuous conversation between past mastery and present imagination.

Table of Contents

Key Focus Areas in Art History

Evolution of Visual Arts

Art history traces how media, techniques, patronage, and ideas change over time. Below is a compact roadmap—pairing

what changed (formal innovations) with why it changed (contexts such as religion, markets,

technology, and politics).

Movements & Turning Points (selected)

- Renaissance (14th–16th c.)

- What: Linear perspective, naturalism, humanist subjects; oil on panel/canvas.

- Why: Civic/religious patronage in Italian city-states; classical revival.

- Artists/Works: Brunelleschi (perspective), Leonardo (Last Supper), Michelangelo (David), Raphael (School of Athens).

- Baroque (17th c.)

- What: Dramatic light, theatrical composition, movement.

- Why: Counter-Reformation persuasion; court spectacle.

- Artists/Works: Caravaggio (The Calling of St. Matthew), Bernini (Ecstasy of Saint Teresa), Velázquez (Las Meninas).

- Neoclassicism & Romanticism (late 18th–early 19th c.)

- What: Moral clarity & antique forms (Neoclassicism) vs. sublime emotion & nature (Romanticism).

- Why: Enlightenment ideals; revolutions; nationalism.

- Artists: David, Ingres; Delacroix, Turner, Géricault.

- Realism & Impressionism (mid–late 19th c.)

- Realism: Social truth, labor, everyday life (Courbet, Daumier).

- Impressionism: En plein air, optical color, transient light (Monet, Renoir, Morisot); break with the academy and embrace of urban modernity.

- Post-Impressionism & Avant-Gardes (c. 1886–1914)

- What: Structure (Cézanne), emotive color (Van Gogh), symbolism (Gauguin), pointillism (Seurat); then Cubism, Fauvism, Futurism.

- Why: Scientific color theory, photography’s challenge, fragmentation of modern life.

- Modernisms (1910s–1960s)

- Dada/Surrealism: Chance, dream, the unconscious (Duchamp; Dalí, Miró).

- Abstract art: Non-objective form (Kandinsky, Mondrian).

- Abstract Expressionism: Gesture, scale, process (Pollock, de Kooning, Lee Krasner).

- Minimalism/Conceptual: Reduction to material/idea (Judd, LeWitt, Kosuth).

- Contemporary Currents (1970s–today)

- Pop & Postmodern: Mass media, irony, appropriation (Warhol, Lichtenstein, Sherman).

- Photography/Video/New Media: From documentary to installation; net art; AI imagery.

- Social Practice & Institutional Critique: Community projects; museum decolonization (Hans Haacke, Theaster Gates).

- Global/Transnational: Biennials; diaspora & identity; environmental art (El Anatsui, Olafur Eliasson).

How to Analyze a Work (toolkit)

- Form: composition, color, line, space, technique, scale.

- Iconography: symbols, narratives, allegories.

- Context: patronage, market, technology, politics, religion, audience.

- Reception: criticism, exhibition history, later reinterpretations.

Development of Architecture

Architecture records the ambitions of societies—uniting structure, space, and symbolism. Materials and engineering methods drive style, while religion, empire, capital, and climate shape function.

Key Architectural Trajectories

- Classical & Islamic Foundations

- Greco-Roman: Orders (Doric/Ionic/Corinthian), arches & vaults; civic urbanism (Parthenon; Pantheon).

- Islamic: Hypostyle halls, muqarnas, courtyards; geometric/arabesque ornament (Great Mosque of Córdoba; Alhambra).

- Gothic (12th–16th c.)

- Pointed arch, ribbed vault, flying buttress; stained glass as “theology in light.”

- Examples: Chartres, Notre-Dame, Cologne Cathedral.

- Renaissance/Baroque

- Renaissance: Proportion, central plans, classical motifs (Brunelleschi, Alberti, Palladio).

- Baroque: Ellipses, dramatic sequences, urban scenography (Bernini & Borromini in Rome).

- Industrial & Modern (19th–20th c.)

- Iron/steel, reinforced concrete, curtain walls; new building types (stations, factories, skyscrapers).

- Modernism: “Form follows function,” open plans, pilotis and ribbon windows (Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye, Mies’s Seagram Building, Bauhaus).

- Postmodern to Present

- Postmodern: Wit, historical quotation, pluralism (Venturi/Scott Brown, Graves).

- Parametric & High-Tech: Digital fabrication, expressive structure (Zaha Hadid, Foster + Partners).

- Sustainable Design: Passive strategies, net-zero buildings, regional materials (glazing optimization, mass timber).

Reading Architecture

- Plan/Section: spatial logic; circulation; public vs. private zones.

- Envelope: façade language, climate performance, symbolism.

- Urbanism: plaza, street wall, skyline; infrastructure connections.

Design and Decorative Arts

Decorative arts—furniture, ceramics, textiles, metalwork—and design bridge daily life and aesthetics. They track technology (from handcraft to mass production) and taste (from ornate to minimal).

Milestones

- Arts & Crafts (c. 1860–1910)

- Handcraft, honest materials, anti-industrial ethics (William Morris; Greene & Greene).

- Art Nouveau (c. 1890–1914)

- Whiplash lines, biomorphic ornament across furniture, glass, architecture.

- Examples: Horta’s Hôtel Tassel; Gaudí’s Casa Batlló and Casa Milà; Gallé glass.

- Bauhaus (1919–1933)

- Unification of art, craft, and technology; modularity; standardization.

- Figures: Gropius, Moholy-Nagy, Marcel Breuer (Wassily Chair).

- Mid-Century Modern (1940s–1960s)

- Warm minimalism; molded plywood, fiberglass, aluminum; human-scaled ergonomics (Eames, Saarinen, Jacobsen).

- Postmodern & Memphis (1980s)

- Colorful laminates, irony, anti-functional exuberance (Ettore Sottsass).

- Contemporary Design

- UX/UI, interactive objects, open-source fabrication, circular design (repairability, recyclability).

Evaluating Design

- Function: usability, ergonomics, safety.

- Form: proportion, material expression, visual hierarchy.

- Impact: lifecycle footprint, inclusivity, cultural resonance.

One Scene, Many Styles: The Evolution of Visual Arts

To see how style shapes meaning, keep a single scene constant and let the art movements transform it.

Shared scene: A small riverside town at dusk. A stone bridge crosses the water; a marketplace bustles in the foreground; a church tower rises behind tiled roofs; a gust of wind moves clouds; two figures exchange goods near a cart; a dog drinks at the river’s edge.

Prehistoric (Cave Painting)

Depiction: The bridge becomes a simple arched mark; people and dog are reduced to stick- and contour-forms; the river is a wavering band. Ocher, charcoal, and clay pigments are dabbed and blown to create silhouettes on rough “rock” ground.

- Hallmarks: Symbol over likeness; earth palette; hand-stencil “signatures”.

- Effect: The town reads like a memory-map or ritual sign, not a view.

This image reimagines a twilight town as if recorded by prehistoric artists. Broad fields of burnt-ochre and sienna mimic mineral pigments on rough rock. Simple charcoal strokes outline a winding river, a low arched bridge, and clustered houses crowned by a tall steeple. On the bank, two stick-figures trade a pouch, while an ox cart waits nearby and a bear or wolf lowers its head to drink—small vignettes of daily life rendered with spare, emblematic marks. To the right, a market stall is suggested by vertical posts and grouped figures; to the left, a bold hand stencil anchors the composition, echoing Paleolithic signatures. Soft, wavy lines overhead imply clouds and the fading light of dusk. The anachronistic subject—town, trade, and church—paired with cave-art conventions (flat silhouettes, limited palette, contour drawing) highlights how visual language can reduce complex scenes to timeless symbols.

Classical Greek

Depiction: Marble relief style: the bridge is proportioned with geometric clarity; figures are idealized, standing in balanced contrapposto; the river is a gently incised flow.

- Hallmarks: Harmony, proportion, measured poise.

- Effect: The scene communicates civic order and moral balance.

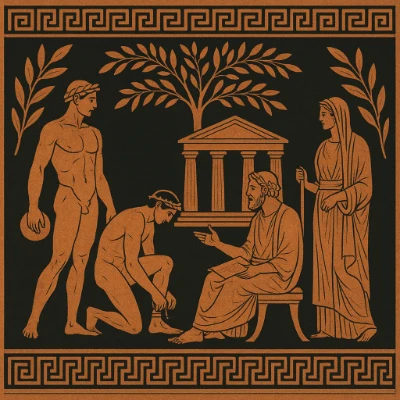

A square “vase painting” composition echoes Classical Greek pottery. Terracotta figures stand out against a black ground: a discus-bearing athlete, a kneeling runner tying his sandal, a seated philosopher gesturing with a scroll, and a robed woman holding a staff. A small Doric temple and olive branches set the sacred-public setting. The image is bordered by repeating meander (Greek key) bands and laurel motifs, using the limited terracotta-and-black palette and flat profile poses characteristic of Attic red-figure ceramics (5th–4th century BCE).

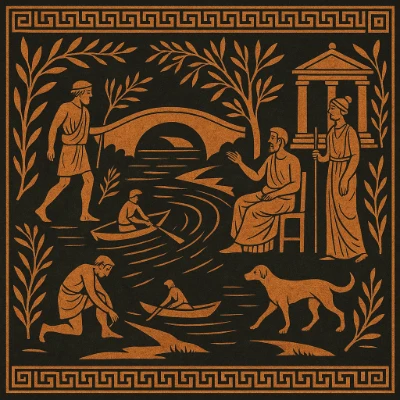

Rendered in the manner of Classical Greek pottery, the image uses a terracotta-on-black palette with flat profile figures and linear incisions. Within a meander and laurel border, a quiet riverside unfolds: a robed woman stands beside a small Doric shrine; a seated philosopher gestures toward boats cutting ripples under an arched bridge; a youth kneels to touch the water while a dog pads along the bank. Olive branches, crisp contours, and limited tones evoke 5th-century BCE Attic red-figure ceramics, translating the modern village motif into an ancient visual language.

East Asian Ink-Wash (Sumi-e / Shui-mo)

Parallel global tradition (Tang–Qing dynasties; 7th–19th c.)

- Depiction:

- Soft washes build mist and evening glow; the arched bridge and tiled roofs are described with a few economical brush lines.

- Houses glow with lantern light; distant mountains dissolve into graded ink tones; a lone boatman drifts beneath the bridge.

- Negative space (blank paper) becomes water and air; calligraphic accents (tree boughs, eaves) articulate rhythm.

- Hallmarks:

- Monochrome ink, value gradation, and brush economy over contour modeling.

- Atmosphere and spirit resonance (qi yun) prioritized above strict linear perspective.

- Literati aesthetics: poetry/inscription, personal cultivation, and nature as moral landscape.

- Effect:

- The town reads as mood and meditation—dusk as a felt experience rather than optical accuracy.

- Invites slow looking: the eye “breathes” with the washes and follows the current of ink.

This image reimagines the riverside-town scene in the vocabulary of classical East Asian ink painting. Broad, diluted washes create misty evening light, while a few decisive brushstrokes define the arched bridge, tiled eaves, and a slim pagoda rising among layered mountains. Lanterns glow from wooden houses along the bank; a solitary boatman glides beneath the bridge, his silhouette echoed in the water. Negative space stands in for sky and river, emphasizing atmosphere and quiet rhythm over hard outlines or Western linear perspective. The overall effect is contemplative—dusk as mood and meditation—aligned with literati ideals of simplicity, balance, and “spirit resonance” (qi yun).

Gothic (Medieval Panel & Stained Glass)

Depiction: Gold-leaf background; the church dominates; bridge and market scale down hierarchically. Figures are elongated; drapery lines are rhythmic; the river is a blue ribbon.

- Hallmarks: Hieratic scale, narrative panels, spiritual emphasis.

- Effect: The town is a stage for salvation history.

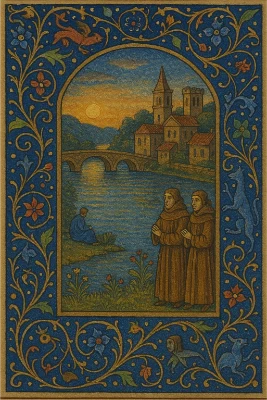

The image emulates a late-medieval book of hours: a central “miniature” depicts a calm river beneath a three-arched bridge, church towers rising behind clustered houses, and two monks in prayerful pose on the bank while a seated figure contemplates the water. Space is shallow and stylized, the light warm and devotional. Surrounding the scene is a dense foliate border painted in deep ultramarine and gold, populated by hybrid beasts and flowers—motifs typical of Gothic illumination. The overall effect is liturgical and narrative, presenting the town as a stage for devotional reflection rather than naturalistic description.

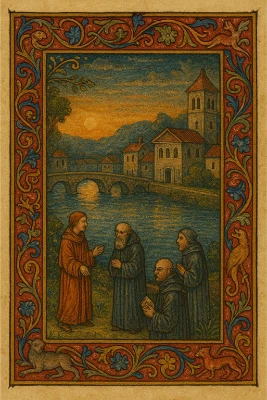

This image imitates a late-medieval book-of-hours miniature: a gold-toned parchment page contains an inset scene of a calm river, a three-arched bridge, clustered houses, and tall church towers under a warm setting sun. In the foreground, four monks—one in russet habit addressing three in dark robes, one holding a book—stand in a shallow, stage-like space typical of Gothic pictorial design. Surrounding the picture is an ornate border of scrolling acanthus, flowers, and small beasts painted in saturated reds and ultramarine. The flattened depth, hieratic grouping of figures, jewel-like colors, and narrative/devotional mood are all hallmarks of Gothic illumination.

This image is designed in the style of a late-medieval illuminated manuscript. The central scene—set under an arched window—depicts a small town at evening: a triple-arched stone bridge spans the river, whose surface catches the orange light of the setting sun; behind it, compact houses and a towered church cluster on the far bank. In the foreground, three monks in brown and grey habits converse quietly on the grass, a typical devotional/narrative focus for Gothic book painting.

The decorated border of scrolling acanthus, blossoms, and tiny animals on parchment grounds the work firmly in Gothic manuscript conventions (Books of Hours, psalters). Colors are tempered and enamel-like, outlines are clear, and scale is slightly hierarchical—architecture and figures simplified for legibility—echoing the period’s emphasis on didactic clarity and sacred reflection. The result is a devotional image where place, time of day, and human presence are harmonized within a framed, jewel-like page.

Renaissance (15th–16th c.)

Depiction: Linear perspective fixes a vanishing point on the bridge; atmospheric perspective cools distant roofs; anatomy and light follow observation; the dog casts a soft shadow.

- Hallmarks: Naturalism, perspective geometry, stable pyramidal compositions.

- Effect: Reasoned space makes human action central and intelligible.

This image stages the riverside town within a classically ordered space. A clear vanishing point aligns with the central arch of the bridge; atmospheric perspective cools the distant hills; and the figures are modeled with observed anatomy and soft, directional light. Architectural volumes—arched bridge, rectilinear façades, and the spired church—are calibrated to proportion and harmony, echoing Quattrocento priorities. The dusk sun warms stone and water alike, casting subtle reflections that anchor the human activity in a rational, intelligible world—hallmarks of Renaissance naturalism and perspective geometry.

Baroque (17th c.)

Depiction: A shaft of sunset light breaks through storm clouds to ignite the market; gestures crescendo; diagonals pull the eye across the bridge; deep chiaroscuro dramatizes forms.

- Hallmarks: Theatrical light, movement, emotional immediacy.

- Effect: Commerce, weather, and faith collide in a moment of fate.

Painted in a Baroque manner, the image stages a theatrical evening along a narrow river. A radiant sky carves through rolling storm clouds, casting ribbons of gold across water and earth. On the near bank, a couple in 17th-century dress stroll past a dog drinking at the shallows while a porter trudges by with a sack. A low arched bridge spans the current; beyond it, an ornate church tower rises above clustered roofs and dark trees. Strong diagonals, swirling cloud forms, and rich contrasts of warm ochres against deep umbers and blues create the sense of movement and heightened drama typical of Baroque landscape painting.

Rococo (18th c.)

Depiction: Pastel palette; curling clouds; elegant figures flirt near the cart; the church becomes a decorative backdrop; the dog is a playful companion.

- Hallmarks: Lightness, ornament, courtly leisure.

- Effect: The scene reads as graceful diversion and delight.

A romantic, Rococo-inspired pastoral scene unfolds at golden hour beside a gentle river. An 18th-century couple in silk finery walks along the bank while a small poodle prances ahead; two ladies converse nearby. Across the water, a covered boat drifts under an arched stone bridge toward a church-steepled village, with a horse-drawn wagon heading home along the road. The sky swirls with soft clouds and warm peach-to-blue gradients, painted in velvety, pastel tones. Flourishing acanthus scrolls frame the image, enhancing its decorative, fête-galante mood.

Neoclassicism (late 18th–early 19th c.)

Depiction: Clean contours, enamel-like paint; figures posed as civic exemplars; the bridge is a rational structure; clouds are disciplined strata.

- Hallmarks: Moral clarity, antique restraint, didactic purpose.

- Effect: The town becomes a stage for virtue and public duty.

Romanticism (19th c.)

Depiction: Dusk swells into sublime weather; wind bends trees; the marketplace feels fragile against nature’s grandeur; brushwork is expressive.

- Hallmarks: Emotion, the sublime, individuality.

- Effect: Human life vibrates within overwhelming atmosphere.

Rendered as a 19th-century Romantic oil, the scene privileges mood over detail. A low sun smolders behind layered clouds, bathing the river in amber reflections. Clustered houses with warm window light climb toward a tapering church spire, while a single boatman pulls at the oars in the foreground. Soft, blended brushwork, deep shadows, and gently receding hills create an enveloping sense of nature and time. The composition’s focus on reverie, solitude, and luminous weather identifies it with Romantic aesthetics.

Realism (mid-19th c.)

Depiction: Unidealized townsfolk bargain; worn stone on the bridge; mud near the riverbank; greys and browns dominate; paint records labor and class.

- Hallmarks: Everyday subjects, social truth, frank surfaces.

- Effect: The market is work, not allegory.

Unidealized details, muted earth tones, and ordinary laborers convey the honest social atmosphere of late-19th-century Realism.

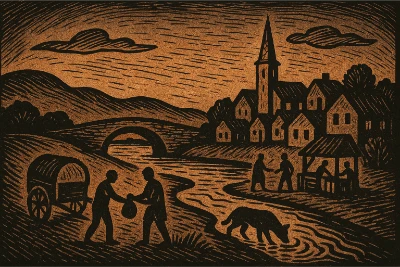

This Realist scene depicts everyday life without embellishment. The foreground shows two townsmen exchanging a sack beside a rutted, muddy bank while a cart stands empty and a dog drinks from the shallows. The stone bridge is worn and heavy; cottages and a church climb the far embankment, their windows dimly aglow as the sun lowers into a clouded sky. The palette favors umbers, greys, and olive greens; forms are carefully observed rather than idealized. Brushwork records texture—river ripples, frayed clothing, and chipped masonry—emphasizing labor, class, and the material facts of place over sentimentality.

Impressionism (late 19th c.)

Depiction: Broken brushstrokes flicker; color notes map reflections on water; forms dissolve in light; the dog is a few luminous touches.

- Hallmarks: Optical color, plein-air light, momentary perception.

- Effect: Time of day becomes the real subject.

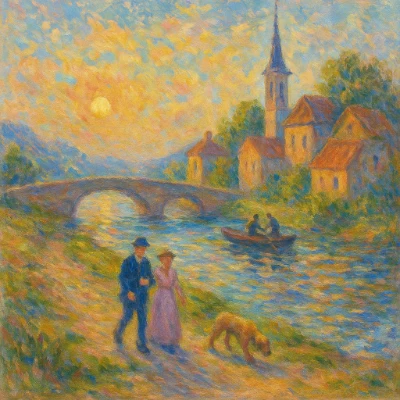

Painted in a late-19th-century Impressionist manner, the scene captures transient light along a small river. Short, visible strokes and broken color let warm oranges and cool blues vibrate across water, sky, and stone. A couple strolls the bank as their dog noses the grass; a rowboat drifts under the arched bridge toward a church-steepled cluster of houses. Reflections ripple in dabs of paint, edges stay soft, and atmosphere—not detail—carries the mood, evoking plein-air observation and the shimmering immediacy typical of Impressionism.

Post-Impressionism

Depiction: The bridge is simplified into strong outlines (Gauguin) or tessellated with ordered strokes (Seurat); colors are symbolic rather than natural.

- Hallmarks: Structure, personal symbolism, experiments with form.

- Effect: Mood and design outweigh optical accuracy.

Painted in a post-Impressionist manner, the scene trades Impressionism’s fleeting haze for intentional structure. Saturated oranges and cobalt blues are laid down in firm, directional strokes, often bounded by dark contours that flatten forms slightly while heightening rhythm. A stone bridge arches across the river; a skiff with two figures drifts through rippling reflections. On the bank, a couple walks two dogs toward a church-steepled cluster of houses. The composition emphasizes design and emotional color—Cézanne-like planes and Van Gogh-style impasto energy—capturing not just the light of evening but its intensity.

Expressionism (early 20th c.)

Depiction: Tilted perspective; acidic colors; the church tower lurches; faces are mask-like; the sky churns with inner anxiety.

- Hallmarks: Distortion for emotional truth, high chroma, urgent line.

- Effect: The town mirrors psychic intensity.

Rendered as a carved relief print, the scene uses thick contours and rhythmic hatch marks to model sky and water. Figures are reduced to emblematic shapes—a trader, a buyer, a wagoner, market vendors—while the church spire anchors a compact skyline. Space is stacked rather than perspectival, and the high black-to-ochre contrast prioritizes atmosphere and feeling over naturalistic depth, aligning the piece with Expressionist practice even as it employs a historical woodcut technique.

Cubism (1907–1914)

Depiction: Bridge, carts, and figures shattered into facets; multiple viewpoints compress space; muted ochres and greys; the river is a lattice of planes.

- Hallmarks: Analytic structure, simultaneous perspectives, collage logic.

- Effect: Seeing is analysis, not illusion.

In a 1907–1914 Cubist idiom, the quiet village is dismantled and reassembled as facets. The church, arched bridge, and rowing skiff appear from shifting viewpoints at once; contours dissolve into angular planes that tessellate across sky and water. A trio of walkers and a dog advance along a gridded bank while the sun is rendered as a flattened disc within intersecting diagonals. The restrained, earthy palette—ochres, umbers, and slate blues—emphasizes structure over atmosphere, and the shallow, quilted space embodies Analytical Cubism’s search for form, volume, and simultaneity.

Futurism (1910s)

Depiction: The market vibrates with speed lines; bridge and dog repeat in rhythmic arcs; dusk becomes kinetic energy.

- Hallmarks: Motion, simultaneity, urban dynamism.

- Effect: Time is sliced and superimposed.

This modernist scene reimagines a quiet riverside village through Futurist dynamism. The sun radiates in blade-like bands, curving across hills, roofs, and water to imply motion and time. Angular forms reduce people, a cart, boatmen, and a dog to silhouettes, emphasizing rhythm over detail. Saturated oranges and teals in layered strokes create depth while echoing Art-Deco palettes. The result is a kinetic landscape where everyday life becomes a choreography of energy and speed.

A stylized village unfolds in sweeping arcs and flat color bands typical of Futurism. Blade-like rays spin out from the sun, curving over hills, bridge, and water to suggest speed and rhythm. Figures and buildings are reduced to crisp silhouettes and interlocking planes in saturated oranges, teals, and deep greens, evoking the energy of early-20th-century modernist posters.

Dada & Surrealism (1916–1940s)

Depiction (collage/surreal): A newspaper-print bridge; a clock floats above the river; the dog casts a fish’s shadow; chance juxtapositions create dream logic.

- Hallmarks: Anti-art wit, automatism, dream imagery.

- Effect: The town becomes the unconscious laid bare.

Abstract Expressionism (1940s–50s)

Depiction: No literal town—gesture stands in for bridge and river; dusky color fields carry the mood of evening; scale engulfs the viewer.

- Hallmarks: Gesture or color-field, immediacy, viewer immersion.

- Effect: The scene is distilled to feeling.

In the spirit of 1940s–50s Abstract Expressionism, the image privileges gesture over outline. Heavy impasto and sweeping, improvisatory marks churn cobalt blues against cadmium yellows and ember reds. Forms of a small town—a steeple, clustered roofs, an arched bridge—surface only intermittently from the brushwork, as do a rowboat, two shadowy walkers, and a dog on the bank. Drags, scrapes, and flicks of paint create an all-over rhythm, turning the river’s reflections into the work’s luminous core. The result evokes action painting’s immediacy while keeping just enough cues for a riverside narrative to cohere.

Pop Art (1960s)

Depiction: The marketplace becomes flat, bright panels with halftone dots; brand logos on awnings; a speech bubble over a vendor.

- Hallmarks: Mass-media imagery, irony, graphic clarity.

- Effect: Everyday commerce becomes cultural critique.

Rendered in a 1960s Pop Art idiom, the riverside town is flattened into graphic shapes and saturated primaries. A sun radiates hard rays across a yellow halftone sky; fields and water snap into blocks of cyan and magenta; houses and a church steeple sit like cut-outs. A couple strolls the bank with two dogs while a red rowboat clips along beneath an arched bridge. Heavy black contours, Ben-Day dot textures, and high-contrast CMYK hues evoke mass-print comics and advertising, reframing the pastoral motif as a crisp, pop-graphic icon.

Minimalism (1960s–70s)

Depiction: The scene reduced to a few rectilinear bands—sky, roofline, river—matte surfaces, industrial finish; figures omitted.

- Hallmarks: Reduction, repetition, objecthood.

- Effect: Perception and space replace narrative.

In a 1960s–70s Minimalist idiom, the scene is distilled to clean, hard-edged shapes and generous negative space. A circular sun balances blocky house forms and a tapering steeple; a single dark band becomes the bridge, its arch cut from the river like a crisp void. Figures and dog are rendered as pared-down silhouettes, while the rowboat is a simple wedge on the water. The restricted palette—cream, burnt orange, and deep teal—keeps focus on proportion, rhythm, and the calm clarity central to Minimalism.

Conceptual Art (late 1960s–)

Depiction: A wall text lists GPS coordinates of the bridge; a map and receipt from the market are displayed; the work asserts that the idea is the artwork.

- Hallmarks: Idea over image; documents, instructions.

- Effect: The town exists as information, not depiction.

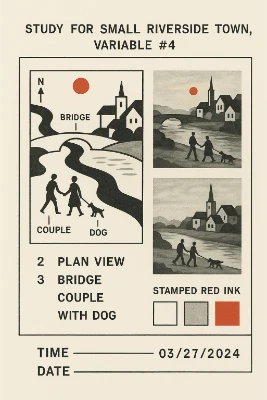

Working in a late-1960s Conceptual Art mode, the image presents the riverside town as information rather than depiction. A labeled diagram marks “BRIDGE,” “COUPLE,” and “DOG” with arrows; adjoining panels show pared-down photographic/photostat views of the same motif. A stamped red square standing for the sun appears alongside a tiny legend and blank “TIME / DATE” lines, echoing instructions and documentation sheets. The neutral palette (black/gray with one accent red) and office-like typography shift emphasis from painterly effect to concept: a reproducible schema for assembling the idea of “small riverside town.”

Contemporary (Global, Digital, Street)

Depiction: A projection-mapped mural animates dusk on the bridge; community stories recorded as QR-coded portraits in the market; the dog triggers AR ripples on the river through a phone app.

- Hallmarks: Hybridity, participation, new media, social engagement.

- Effect: The scene becomes shared, interactive experience.

Classroom/Studio Use:

- Choose one subject (our riverside town) and sketch it in three contrasting styles.

- Annotate choices for composition, light, color, line, space, and intended mood.

- Present side-by-side to discuss how style re-codes meaning.

Art as Cultural Expression

Art encodes beliefs, power, memory, and identity. Reading works alongside rituals, laws, and media reveals how cultures represent themselves—and contest those representations.

Religious & Ritual Art

- Byzantine: mosaics as theology in gold light (Hagia Sophia).

- Hindu: temple sculpture, darshan, cyclical time (Khajuraho; Chola bronzes).

- Islamic: aniconic geometry and calligraphy; Qur’anic manuscripts; tilework (Isfahan; Topkapi).

Power, Protest, and the Public Sphere

- Propaganda/State Imagery: Roman imperial portraiture; Baroque court spectacle; socialist realism.

- Critique & Witness: Goya’s Third of May 1808; Rivera’s murals; Picasso’s Guernica; Ai Weiwei’s installations.

- Street/Public Art: Graffiti, memorials, community murals; temporary monuments and counter-monuments.

Identity & Representation

- Feminist & Queer Art: Judy Chicago, Carrie Mae Weems, Felix Gonzalez-Torres—challenging the canon and gaze.

- Black Atlantic/Diaspora: Faith Ringgold, Kerry James Marshall, El Anatsui—memory, migration, and modernity.

- Indigeneity & Revitalization: Māori weaving, Inuit printmaking, Native American ledger art—continuity and innovation.

Memory, Trauma, and Museums

- Holocaust, apartheid, and genocide memorial practices; ethics of display.

- Restitution and repatriation; provenance research; decolonizing the museum.

Global Perspectives in Art History

A global lens tracks exchange along trade routes, empire, and diaspora, showing how forms travel, hybridize, and acquire new meanings.

Regions & Traditions (snapshot)

- Africa: Ife/Benin brass casting; Akan goldweights; Kongo power figures; contemporary biennials (Dakar, Lagos).

- South & East Asia: Mughal miniatures; Rajput painting; Chinese literati landscapes; Japanese ukiyo-e; Korean celadon; contemporary ink art.

- Americas: Maya stelae; Andean textiles; Northwest Coast formline; Mexican muralism; Chicanx art.

- Oceania: Polynesian tattoo and tapa; Aboriginal songlines and dot painting; Melanesian carving.

- Islamicate Worlds: Persianate book arts; Ottoman architecture; Moroccan zellige; modern calligraphic abstraction.

Cross-Cultural Currents

- Trade Routes: Silk Roads spread paper, pigments, motifs; Indian cottons reshape European pattern books.

- Transculturation: Moorish Spain mediates Islamicate geometry into European ornament; Japonisme transforms French modernism.

- Diaspora: Caribbean, African, and South Asian diasporas reframe identity in London, Paris, New York, Toronto.

- Global Art System: Biennials, art fairs, NGOs, and digital platforms alter patronage and visibility.

Methods & Skills

- Compare materials and meanings across regions; replace single-origin “influence” stories with multi-directional exchange.

- Weigh translation, appropriation, and ethics when works cross borders—who benefits and who speaks?

Applications of Art History

Understanding Cultural Values

Works of art function as archives of belief systems, power relations, and everyday life. Reading images, objects, and buildings alongside their patrons, audiences, and uses enables us to reconstruct what communities valued—and how those values changed.

- Ideology & Power: Court portraiture, triumphal architecture, and civic monuments encode authority, legitimacy, and statecraft.

- Ritual & Spirituality: Altarpieces, icons, mandalas, and mosque decoration visualize cosmologies and guide devotional practice.

- Social Life: Genre scenes, textiles, and ceramics reveal fashion, labor, and trade networks often missing from written records.

- Example: The theatrical scale and splendor of Baroque Rome (Bernini, Borromini) communicated Counter-Reformation zeal and papal power, while Dutch Golden Age interiors documented a rising merchant class and Protestant domestic virtues.

Aesthetic Appreciation & Visual Literacy

Art-historical training sharpens attention to form, technique, and style—skills transferable to all visual media.

- Close Looking: Analyze composition, color, scale, texture, and material to understand how meaning is produced.

- Comparative Method: Track motifs and methods across regions and periods to recognize continuity, rupture, and hybridity.

- Interpretive Frameworks: Apply iconography, semiotics, feminism, postcolonial theory, and reception studies to deepen readings.

- Outcome: More nuanced museum visits, better critique of advertising and film, and stronger design judgment in professional contexts.

Preservation of Cultural Heritage

Conservators, curators, and heritage professionals use art-historical research to safeguard objects and sites.

- Conservation Science: Technical study (X-radiography, infrared reflectography, pigment analysis) informs cleaning and stabilization strategies.

- Documentation & Provenance: Cataloging, archival work, and ownership research support legal title, repatriation, and insurance.

- Risk & Climate Planning: Mitigation for floods, heat, and conflict; emergency packing and digital backups.

- Examples:

- Cleaning of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel frescoes revealed original chroma and workshop practice.

- UNESCO campaigns and local stewardship to stabilize the Parthenon and safeguard Angkor Wat.

Inspiring Contemporary Art & Design

Makers mine the past for techniques, narratives, and forms—often recontextualizing them to address present concerns.

- Technique Transfer: Revival of fresco, tempera, natural dyes, and craft lineages within sustainable design.

- Reinterpretation: Postmodern quotation, remix, and digital appropriation interrogate authorship and originality.

- Case Studies:

- Contemporary architects adapt Gothic light and verticality to create low-carbon timber cathedrals.

- Photographers restage Renaissance compositions to critique race and gender in the canon.

Public History, Museums, & Cultural Diplomacy

Exhibitions and cultural programs translate scholarship for broad audiences and foster international dialogue.

- Curation & Education: Write labels, design interpretive media, and lead programs that connect collections to communities.

- Soft Power: Traveling shows, loans, and restorations build trust and showcase shared heritage.

- Equity & Inclusion: Community co-curation, multilingual access, and decolonizing practices broaden representation.

Policy, Law, & Ethics

Art history informs legal frameworks and ethical standards around ownership, restitution, and the art market.

- Cultural Property & Repatriation: Research underpins returns of looted antiquities and Nazi-era art.

- Intellectual Property: Image rights, fair use, and artist resale royalties.

- Market Due Diligence: Authenticity, condition, and context assessments for collectors, auction houses, and insurers.

Digital Humanities & Emerging Technologies

New tools expand access and analysis while raising fresh questions about preservation and authorship.

- Digitization & Access: IIIF image standards, open collections, and 3D scans for research and teaching.

- Computational Analysis: Style clustering, material mapping, and network graphs reveal patterns across large corpora.

- XR Interpretation: AR/VR reconstructions of lost spaces and original polychromy.

- AI & Ethics: Provenance verification vs. deep-fake risk; dataset transparency and cultural sensitivity.

Economic Development, Creative Industries & Tourism

Heritage districts, biennials, and design sectors drive local economies when paired with responsible planning.

- Place-Making: Adaptive reuse of industrial sites into cultural hubs.

- Cultural Routes: Museums and festivals generate employment and sustainable visitation.

- Entrepreneurship: Galleries, publishing, conservation studios, and cultural tech startups.

Health, Well-Being, & Community

Engagement with art supports mental health, empathy, and social connection.

- Museum Medicine: Programs for dementia care, veterans, and teens build memory, focus, and belonging.

- Public Art & Civic Repair: Memorials and murals foster dialogue, remembrance, and healing after trauma.

Careers & Transferable Skills

Art history cultivates research, writing, visual analysis, and project management applicable across sectors.

- Paths: Curator, educator, conservator, registrar, archivist, art lawyer, arts journalist, art advisor, gallery/museum operations, cultural policy, UX/UI, creative strategy.

- Skills: evidence-based argumentation, intercultural fluency, ethical decision-making, grant writing, and stakeholder engagement.

Why Study Art History

Understanding Visual Culture Across Time and Civilizations

- What you learn: how form (composition, color, material, scale) produces meaning; how style travels through trade and empire; how audiences interpret works differently across time.

- Why it matters: visual media structure public memory, national narratives, and everyday choices—from monuments and museums to branding and social platforms.

Exploring the Intersections of Art, History, and Society

- Historical arcs: the civic humanism of the Renaissance; Baroque art and the Counter-Reformation; art and industrialization; colonial encounter and anti-colonial modernisms; postwar abstraction and Cold War diplomacy; feminist, Black, Indigenous, and queer interventions; the Anthropocene and eco-aesthetics.

- Methods you’ll practice: formal and comparative analysis, iconography, social history of art, postcolonial critique, reception studies, and material/technical study.

- Result: a richer, evidence-based account of the past that integrates images, texts, objects, and spaces.

Developing Visual Literacy and Critical Thinking

- Close looking: identify visual strategies (light, perspective, texture), craft choices (pigments, binders, supports), and display contexts (altars, palaces, billboards).

- Argument & evidence: build interpretations that connect what you see to primary sources, technical data, and historical scholarship.

- Transferable outcomes: sharper analytical writing, persuasive presentations, ethical evaluation of visual claims (advertising, political imagery, AI-generated content).

Engaging with Museums, Heritage, and Conservation

- Curation & education: label writing, gallery design, accessible storytelling, community co-curation, and inclusive practice.

- Conservation & science: imaging (X-ray, IRR), pigment analysis, climate mitigation, and preventive care for works on paper, textiles, sculpture, and architecture.

- Policy & law: provenance, restitution, cultural property, and repatriation frameworks.

- Hands-on learning: object studies, collections management, exhibition proposals, and digital cataloguing (IIIF, metadata).

Harnessing Digital Tools and Emerging Technologies

- Research: high-resolution open collections, 3D scans, GIS mapping of artistic networks, and computational pattern analysis for style, trade, and workshop practice.

- Interpretation: AR/VR reconstructions of lost architecture and original polychromy; interactive timelines and story maps for public engagement.

- Ethics: transparency in datasets, consent and cultural sensitivity, and critical awareness of deep-fake risks versus authentication tools.

Preparing for Diverse Careers in the Arts and Beyond

| Career Pathways | Core Skills Gained | Sample University-Level Tasks |

|---|---|---|

| Museum & Gallery (curator, educator, registrar) | Collections research, label writing, audience engagement, collections care | Design a thematic exhibition with checklist, floor plan, and interpretive texts |

| Conservation & Heritage | Technical analysis, condition reporting, risk assessment, ethics | Create a conservation treatment proposal with imaging and material study |

| Art Market & Cultural Policy | Provenance, valuation, due diligence, legal frameworks | Draft a provenance dossier; analyze a restitution case study |

| Media, Design, Education, Law | Visual literacy, argumentation, writing, stakeholder communication | Visual rhetoric analysis; curatorial storytelling for multiple audiences |

What Studying Art History Looks Like

- Seminars & studios: discussion-based classes with object handling or site visits.

- Primary sources: artists’ letters, contracts, travelogues, criticism, restoration records.

- Assessment: visual analyses, research essays, catalogue entries, exhibition proposals, digital projects (3D models, interactive maps).

- Field learning: museums, archives, heritage sites, and community arts organizations.

Art History: Conclusion

Art history is far more than a catalogue of masterpieces; it is a disciplined way of seeing that connects images, objects, and built spaces to the people and systems that produced them. By tracing how patrons, technologies, beliefs, and audiences shaped the visual world—from Paleolithic caves and Kushite pyramids to Baroque chapels, Edo prints, Bauhaus workshops, and immersive digital art—we recover the stories of power, devotion, resistance, pleasure, and memory that structure human life.

Studying art history refines visual literacy and critical judgment. It teaches close looking and evidence-based interpretation; it joins formal analysis to archival research, scientific imaging, and ethical reflection on ownership, restitution, and conservation. In doing so, it illuminates how images persuade, monuments commemorate or exclude, museums narrate identity, and design shapes daily behavior.

- Read visual and spatial evidence with the same rigor applied to texts.

- Link artworks to their material making, social function, and global circulation.

- Evaluate museum practices, provenance, conservation ethics, and cultural policy.

- Communicate clearly across audiences—through writing, curation, and digital storytelling.

Looking ahead, the field remains vital to contemporary questions: decolonizing collections and returning cultural property, documenting heritage at risk from climate change and war, using digital tools to reconstruct lost contexts, and ensuring that future technologies are deployed with cultural sensitivity. The result is a discipline that is historically grounded, globally attentive, and civically engaged.

In short, art history offers a window into the diversity and complexity of human expression and a mirror that helps us understand our own image-saturated present. It enlarges empathy, deepens cultural understanding, and shows how creativity—across time and place—has imagined, challenged, and remade the world we inhabit.

Art History – Frequently Asked Questions

What is Art History, and what does it study?

Art History studies visual art across time and cultures — including painting, sculpture, architecture, photography, and more — in order to understand how people express ideas, beliefs, identities, and social change through images and spaces.

How does Art History differ from studio art or art-making?

Unlike studio art, which focuses on creating new works, Art History analyses existing works and contexts. It examines style, technique, iconography, patronage, cultural meaning, historical context, and how art reflects or shapes society — rather than producing art itself.

What kinds of questions does Art History ask?

Art historians ask: Who made this artwork, when and why? What materials and techniques were used? What cultural, religious or political ideas does it express? How was it displayed or received? How did artists influence each other across time and place?

What types of sources are used in Art History research?

Sources include paintings, sculptures, drawings, buildings, photographs, manuscripts, prints, advertisements, digital media, as well as historical documents, letters, critiques, and archival records. Art historians also use technical analysis, provenance records, cultural context, and comparative works to interpret meaning and significance.

Why is Art History relevant beyond art museums?

Art History helps us understand identity, power, ideology and social change because art often reflects culture, politics, religion, and social values. It can reveal how societies view beauty, authority, memory, and resistance. Understanding art fosters critical thinking about today's visual culture, media, architecture, design, advertising, and public space.

What skills does studying Art History develop?

You will develop skills in visual analysis, critical thinking, contextual research, comparative analysis, writing, and interpreting historical and cultural meaning. You will learn to read images and spaces like texts — analysing symbolism, style, and social context — which is valuable in many fields beyond art.

What career paths can Art History lead to?

Possible paths include roles in museums and galleries, heritage and conservation, curation, research and education, art criticism, publishing, cultural institutions, arts administration, media and journalism, academic study, and roles in architecture, design, or cultural policy.

How does Art History relate to other subjects like history, cultural studies, or anthropology?

Art History overlaps with history, cultural studies, anthropology, media studies, and architecture: it examines how art and visual culture reflect social, political, and cultural processes. By studying art in historical and social context, you gain cross-disciplinary insight into identity, power, migration, technology, and global exchange.

Is prior artistic skill required to study Art History?

No. Art History focuses on analysis, interpretation, and critical thinking rather than the ability to draw or paint. While familiarity with basic visual vocabulary helps (such as composition, colour, form), what matters most is observation, curiosity, reading and writing skills, and the ability to analyse cultural context.

How are Art History courses typically assessed at university?

Assessment often includes essays, image or object commentaries, presentations, source analysis, comparative studies, and sometimes curatorial or research projects. You may be asked to interpret artworks in social and historical context or compare different periods or cultures critically.

How can I prepare now for studying Art History?

You can start by visiting museums (physically or online), reading about art movements and history, analysing images and architecture around you, and practising writing short reflections on what you see. Use critical questions: Who made this art? What does it say about society, identity, or values? Observing visual culture with a historical and cultural lens helps build the skills needed for Art History study.

Why is Art History important in modern contexts with digital media and globalisation?

In a globalised, media-saturated world, visual culture is everywhere — in advertising, social media, architecture, design, and virtual spaces. Art History equips you to understand, critique, and contribute to visual culture with awareness of history, identity, representation, and social impact. It helps bring historical perspective to contemporary design, media, and public discourse.

Art History: Review Questions and Answers:

1. What is art history and why is it important to study?

Answer: Art history is the study of visual art in its historical context, examining the evolution of artistic styles, techniques, and cultural influences over time. It is important to study because it provides insights into the social, political, and economic conditions that have shaped artistic expression. Through art history, we gain a deeper understanding of how art reflects and influences human experience, identity, and societal values. This field not only enriches our appreciation for beauty and creativity but also fosters critical thinking about cultural narratives and historical change.

2. How do art historians analyze visual culture?

Answer: Art historians analyze visual culture by closely examining artworks, including their composition, symbolism, and technique. They consider the historical context and cultural background in which an artwork was produced to understand its significance. This analysis often involves interpreting the iconography, style, and medium to reveal underlying messages and social commentary. By synthesizing various sources of evidence, art historians can construct a coherent narrative that explains the evolution of visual expression across different periods.

3. What methodologies are commonly used in art historical research?

Answer: Art historical research employs a range of methodologies, including formal analysis, iconography, and contextual studies. Formal analysis focuses on the visual elements of an artwork such as line, color, and composition, while iconography interprets the symbols and motifs present in the work. Contextual studies examine the social, political, and cultural conditions that influenced the creation and reception of art. These combined approaches enable art historians to develop a nuanced understanding of how art functions both as a visual language and a reflection of its historical moment.

4. How can art history contribute to our understanding of cultural identity?

Answer: Art history contributes to our understanding of cultural identity by exploring how art reflects the values, beliefs, and traditions of a society. It examines the ways in which visual art serves as a repository of cultural memory and a medium for expressing collective identity. By studying the evolution of art within different cultural contexts, we can observe how identities are constructed, challenged, and transformed over time. This understanding helps to appreciate the diversity of human expression and highlights the role of art in shaping societal narratives and individual self-perception.

5. What impact has technology had on the study and preservation of art history?

Answer: Technology has profoundly impacted the study and preservation of art history by enabling the digital archiving, analysis, and dissemination of artworks. High-resolution imaging, 3D modeling, and virtual reality allow researchers to examine artworks in unprecedented detail and preserve them for future generations. These technological advances have also democratized access to cultural heritage, making art more accessible to a global audience. As a result, technology not only enhances research capabilities but also plays a crucial role in safeguarding artistic legacies.

6. How does art history intersect with other academic disciplines?

Answer: Art history intersects with disciplines such as anthropology, sociology, and literature by exploring how art reflects broader cultural and social dynamics. This interdisciplinary approach allows scholars to analyze how artistic expressions are influenced by historical events, social structures, and philosophical ideas. By drawing on methodologies from various fields, art historians can offer richer, more complex interpretations of art and its impact on society. The integration of multiple perspectives enriches our understanding of both art and the cultural contexts in which it is created.

7. What role does patronage play in the creation and dissemination of art?

Answer: Patronage plays a significant role in the creation and dissemination of art by providing the financial support and social networks necessary for artists to produce their work. Historically, patrons such as monarchs, religious institutions, and wealthy individuals have influenced artistic production by commissioning works that reflect their values and ambitions. This relationship not only affects the subject matter and style of art but also contributes to its circulation and preservation. Understanding patronage helps art historians reveal the economic and political forces that shape artistic movements and cultural production.

8. How can art history be used to critique contemporary social and political issues?

Answer: Art history can be used to critique contemporary social and political issues by analyzing the visual rhetoric and symbolic representations found in art. It offers a critical lens through which to examine how power, ideology, and resistance are expressed and contested in visual culture. By comparing historical artworks with contemporary artistic expressions, art historians can identify recurring themes and shifts in societal values. This critical approach not only deepens our understanding of past and present cultures but also informs discussions about social justice and political change.

9. How do art historians interpret the symbolism present in different art movements?

Answer: Art historians interpret the symbolism present in different art movements by analyzing the visual elements and thematic content of artworks within their historical and cultural contexts. Each art movement is characterized by distinctive symbols and motifs that convey specific ideas and reflect the zeitgeist of its era. By studying these symbols, scholars can uncover the underlying messages and ideological currents that drove artistic innovation. This interpretative process reveals how art communicates complex concepts about society, identity, and human experience, offering valuable insights into the cultural significance of various movements.

10. How does the study of art history enhance our critical understanding of visual narratives in media?

Answer: The study of art history enhances our critical understanding of visual narratives in media by providing tools to decode the language of images and symbols. Art history teaches us to look beyond the surface, examining the composition, context, and historical background of visual works. This critical approach enables us to appreciate the deliberate choices made by creators in conveying messages, shaping public opinion, and influencing cultural discourse. By applying art historical methodologies, we become more discerning consumers of visual media, capable of interpreting the deeper meanings embedded in the images that permeate modern society.

Art History: Thought-Provoking Questions and Answers:

1. How might digital technology transform the preservation and study of art history in the coming decades?

Answer:

Digital technology is set to transform the preservation and study of art history by enabling the creation of high-resolution digital archives and interactive virtual museums. These tools allow scholars to document and analyze artworks with unprecedented detail, preserving fragile pieces for future generations and making them accessible to a global audience. Digital platforms facilitate collaborative research and the use of advanced analytical methods such as AI-driven image recognition and 3D modeling, which can reveal new insights into artistic techniques and historical contexts. The digital revolution not only broadens access to cultural heritage but also enhances our ability to engage with art in innovative and dynamic ways.

Moreover, the integration of digital technology into art historical research encourages interdisciplinary approaches and the democratization of art education. Virtual reality experiences and augmented reality applications can bring art to life for students and enthusiasts, allowing them to explore historical artworks in immersive environments. As these technologies continue to evolve, they will likely redefine traditional research methodologies and teaching practices in art history, ensuring that the field remains relevant and responsive to the digital age.

2. In what ways can interdisciplinary research enrich our understanding of art history?

Answer:

Interdisciplinary research enriches our understanding of art history by integrating perspectives from fields such as anthropology, sociology, and cultural studies, which provide broader context and depth to the analysis of art. By combining methodologies and theoretical frameworks from various disciplines, art historians can explore how social, political, and economic factors influence artistic production and cultural expression. This collaborative approach reveals the complex interplay between art and society, highlighting the ways in which artworks reflect and shape historical events and social transformations. The fusion of multiple perspectives fosters more nuanced interpretations that transcend traditional disciplinary boundaries.

Furthermore, interdisciplinary research encourages the use of innovative techniques such as digital humanities, which leverage data analytics and visualization tools to uncover patterns in large collections of artworks. These methods offer new insights into trends and influences across different time periods and regions. As a result, interdisciplinary research not only enhances the academic study of art history but also provides valuable context for contemporary cultural debates, making it a vital component of modern scholarship.

3. How can art history challenge dominant cultural narratives and promote alternative perspectives?

Answer:

Art history can challenge dominant cultural narratives by critically analyzing how mainstream artistic expressions often reinforce established power structures and ideologies. Scholars in art history scrutinize the provenance, context, and reception of artworks to reveal hidden biases and marginalize voices that have been historically overlooked. By highlighting the contributions of underrepresented artists and exploring alternative artistic movements, art history promotes a more inclusive understanding of cultural heritage. This critical engagement with art enables the questioning of traditional narratives and opens up space for new interpretations that reflect diverse experiences and identities.

In doing so, art history provides a platform for dialogue and resistance against cultural hegemony. It encourages the reassessment of historical events and artistic legacies, fostering a more pluralistic and dynamic cultural discourse. By elevating alternative perspectives, art history contributes to the deconstruction of monolithic narratives and supports the empowerment of marginalized communities, ultimately promoting social and cultural transformation.

4. What impact does globalization have on art and its interpretation?

Answer:

Globalization has a profound impact on art and its interpretation by facilitating the cross-cultural exchange of ideas, styles, and techniques. As artists are exposed to diverse cultural influences, they often create hybrid forms of expression that challenge traditional boundaries and reflect the complexities of a connected world. This global intermingling enriches artistic production, leading to innovative and eclectic works that transcend local traditions. The interpretation of art in a global context requires an understanding of both the historical roots and the contemporary dynamics that shape artistic expression, resulting in a more nuanced and multifaceted analysis.

Furthermore, globalization impacts the dissemination of art, making it more accessible to a global audience through digital platforms and international exhibitions. This widespread access encourages a diversity of interpretations and opens up dialogues between different cultures. However, globalization also raises questions about cultural homogenization and the potential loss of distinct artistic identities. By critically engaging with these issues, art historians can explore the tensions between global influences and local traditions, offering insights into the evolving nature of art in the modern world.

5. How might the study of art history contribute to environmental and sustainability movements?

Answer:

The study of art history can contribute to environmental and sustainability movements by exploring how artists have historically represented nature and environmental themes. Art serves as a powerful medium for communicating the beauty and fragility of the natural world, often inspiring awareness and action on environmental issues. Through the analysis of artworks that depict landscapes, flora, and fauna, art historians can trace the evolution of human attitudes toward nature and the impact of industrialization and environmental degradation. This critical examination reveals how cultural representations of nature have influenced public perceptions and policy decisions related to environmental conservation.

Moreover, contemporary artists are increasingly using their work to address urgent sustainability challenges, prompting art historians to engage with eco-criticism and environmental aesthetics. By documenting and analyzing these artistic responses, the field can offer insights into the cultural dimensions of environmentalism and advocate for a more sustainable relationship between humans and nature. The intersection of art history and environmental studies thus provides a unique lens through which to understand and promote sustainability, inspiring both creative expression and social change.

6. How can museums and cultural institutions use art history to engage the public in critical cultural dialogue?

Answer:

Museums and cultural institutions can use art history to engage the public in critical cultural dialogue by curating exhibitions that highlight diverse perspectives and challenge conventional narratives. Through innovative displays and interactive installations, these institutions can create immersive experiences that encourage visitors to question and reinterpret the art on view. By providing historical context and diverse viewpoints, museums can foster a deeper understanding of the cultural, political, and social forces that shape artistic expression. This engagement not only enriches public knowledge but also stimulates discussion and reflection on contemporary cultural issues.

Additionally, museums can host public lectures, workshops, and panel discussions that invite experts and community members to share their insights on art and culture. These programs can serve as platforms for dialogue, enabling audiences to explore different interpretations and connect with the broader cultural discourse. By actively involving the public in the exploration of art history, cultural institutions play a crucial role in promoting critical thinking and social awareness, thereby contributing to a more informed and engaged society.

7. How might the rise of social media influence the dissemination and reception of art historical scholarship?

Answer:

The rise of social media is profoundly influencing the dissemination and reception of art historical scholarship by creating new channels for communication and engagement. Platforms like Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook allow scholars to share their research, images, and insights with a global audience, making art history more accessible and interactive. Social media facilitates the rapid exchange of ideas, enabling real-time discussions and collaborations that can enrich scholarly work. This democratization of information has the potential to broaden the impact of art historical research beyond traditional academic circles, reaching a wider and more diverse audience.

However, the digital landscape also presents challenges, such as the risk of oversimplification and the spread of misinformation. Balancing scholarly rigor with the need for engaging, easily digestible content requires innovative approaches and a critical understanding of digital communication. Despite these challenges, social media offers exciting opportunities for art historians to connect with the public, promote cultural education, and foster a vibrant, global community of art enthusiasts.

8. How can art historical research influence contemporary art and creative practice?

Answer:

Art historical research can significantly influence contemporary art and creative practice by providing a rich source of inspiration and critical perspective on past artistic movements and techniques. By studying historical art, contemporary artists can draw on a wealth of visual language, symbolism, and narrative strategies to inform their work. This research enables artists to engage with historical themes in new and innovative ways, often reinterpreting traditional forms to address modern issues and cultural debates. Furthermore, art historical insights encourage a dialogue between past and present, enriching the creative process and contributing to the evolution of artistic expression.

In addition, art historical research can challenge contemporary artists to consider the socio-political contexts of their work, fostering a deeper engagement with cultural and historical narratives. This critical reflection can lead to more thoughtful and impactful art that resonates with diverse audiences. By bridging the gap between historical scholarship and creative practice, art historical research not only enhances the aesthetic quality of contemporary art but also contributes to a broader cultural conversation about identity, memory, and social change.

9. What role do personal narratives and memory play in the interpretation of art history?

Answer:

Personal narratives and memory play a vital role in the interpretation of art history by adding emotional depth and subjective context to the analysis of artworks. These elements help to humanize historical events and cultural expressions, allowing scholars to connect individual experiences with broader social and political trends. By incorporating personal stories and collective memory, art historians can explore how art reflects and shapes personal identity and cultural heritage. This approach enriches the understanding of art by revealing the intimate and often complex relationship between the creator, the artwork, and the audience.

Furthermore, the inclusion of personal narratives challenges the traditional, objective methods of art historical analysis by acknowledging the influence of individual perception and lived experience. It opens up space for alternative interpretations and diverse perspectives that might otherwise be overlooked. In doing so, art history becomes a more dynamic and inclusive field, capable of capturing the multifaceted dimensions of human experience as expressed through art.

10. How might economic factors influence the production and consumption of art in historical contexts?

Answer:

Economic factors have long influenced the production and consumption of art, as financial resources and market dynamics play a critical role in determining what art is created and who can access it. In historical contexts, patronage from wealthy individuals, institutions, and governments often shaped artistic trends, directing the subject matter, style, and scale of artworks. Economic conditions can also affect the distribution and preservation of art, with periods of prosperity leading to flourishing artistic production and economic downturns resulting in diminished cultural output. By examining economic factors alongside cultural and social influences, art historians can gain a more comprehensive understanding of how art reflects and responds to the economic realities of its time.

Moreover, the study of economic influences on art reveals the interconnectedness of culture and commerce, illustrating how art functions as both a creative expression and a commodity. This dual role can inform contemporary discussions about the value of art, cultural policy, and the ethics of art production and consumption. Through such analysis, art history provides insights into the ways in which economic conditions shape artistic innovation and cultural heritage.

11. How can the study of art history contribute to cultural diplomacy and international relations?

Answer:

The study of art history can contribute to cultural diplomacy and international relations by highlighting the shared cultural heritage and artistic achievements of different societies. Art serves as a universal language that can bridge cultural divides and promote mutual understanding among nations. By examining historical artworks and cultural exchanges, art historians can reveal common values and themes that resonate across borders, fostering dialogue and cooperation. This cultural connection can play a significant role in diplomatic efforts, as it helps build bridges between communities and nations through a shared appreciation of art and history.

Additionally, art history offers valuable insights into the cultural narratives that underpin national identities and international perceptions. These insights can inform cultural exchange programs, exhibitions, and collaborative projects that enhance diplomatic relationships. By leveraging art as a tool for diplomacy, countries can work together to promote peace, cultural exchange, and mutual respect, ultimately contributing to a more harmonious global community.

12. How might emerging trends in sustainability influence contemporary art and its historical interpretation?

Answer:

Emerging trends in sustainability are increasingly influencing contemporary art, and this shift is prompting art historians to reconsider the relationship between art, the environment, and societal values. Contemporary artists are exploring themes of ecological responsibility, climate change, and resource conservation, often using sustainable materials and practices in their work. This new focus not only reflects current environmental concerns but also challenges traditional aesthetic norms and the art market’s approach to materiality. As a result, art history is evolving to include analyses that consider the environmental impact and sustainability of artistic practices, offering fresh perspectives on both contemporary and historical art.

Moreover, the incorporation of sustainability into art and its interpretation invites a broader discussion about the role of creativity in addressing global challenges. Art historians can examine how sustainable practices in art production and the thematic exploration of ecological issues are reshaping cultural narratives and societal priorities. This evolving discourse enriches our understanding of art’s potential to inspire social change and highlights the interconnection between environmental sustainability and cultural expression. By engaging with these emerging trends, scholars can offer innovative interpretations that reflect the pressing concerns of our time and contribute to a more sustainable cultural future.

Last updated: