Postcolonial cultural studies examine how societies emerging from colonial domination reclaim and redefine their identities, narratives, and institutions. By unpacking the legacy of empire, this field explores how power, culture, and resistance intersect, especially in formerly colonized regions. A critical framework is offered by the history of ideas, which traces the philosophical underpinnings of colonial rule and the intellectual roots of anticolonial thought. These studies also draw upon the history of political systems to explore how postcolonial states restructured governance amid inherited colonial institutions.

Debates surrounding post-colonial constitutionalism are especially relevant, as newly independent nations struggled to balance imported legal frameworks with indigenous traditions. Some sought inspiration in revolutionary constitutions, while others contended with legacies of fragmentation and suppression, often visible in their electoral history and ongoing debates over electoral fraud and integrity. The entanglement of culture and politics also reveals itself in struggles over national memory, often preserved or challenged through history of social movements.

Cultural identity is not only shaped by state politics but also by educational institutions. Insights from education history show how colonial curricula reinforced hierarchical worldviews, while postcolonial efforts aimed to decolonize knowledge systems. These pedagogical battles often overlap with contests over spiritual and symbolic frameworks documented in religious and spiritual history. At the popular level, popular culture becomes a battleground where stereotypes are subverted, and hybrid identities flourish.

Postcolonial studies also extend to global arenas of diplomacy and warfare. The effects of colonization linger in the realm of diplomatic history and continue to shape the actions of influential diplomatic personalities. The manipulation of soft power through economic diplomacy and alliances—examined in the history of alliances—often continues to echo colonial patterns of influence and dependence.

Violence, too, is a recurring theme in the postcolonial experience. The economic dimension of imperial conflict is highlighted in the economic history of warfare, while strategies of resistance such as guerrilla warfare and insurgency studies reveal how local actors contested global powers. These themes interweave with economic considerations that remain central to postcolonial nations today. The economic history of formerly colonized countries often tells a tale of extractive colonial policies and subsequent challenges in development.

In tracing the evolution of markets and state economies, scholars revisit the history of political economy and the history of economic thought, which reveal how Western ideologies dominated discourse and shaped global hierarchies. Theoretical refinements are further explored in economic thought and theory, enabling critiques that support decolonial economic models.

Finally, it is essential to view postcolonial studies in the context of broader historical patterns. The foundational discipline of history enables a nuanced approach to cultural legacies and structural transformations. These investigations are deepened when considered alongside frameworks that assess the roles of electoral systems and political parties, or when viewed through the lens of shifting identities and structural resistance that define the ongoing journey of postcolonial societies.

This richly layered illustration visualizes key themes in postcolonial cultural studies. At the center, a globe encircled by chains that snap open represents the end of formal empire and the ongoing work of decolonization. A raised fist, protest crowds, and Lady Justice evoke struggles for sovereignty, rights, and legal redress. National flags and maritime motifs recall the routes of conquest, trade, and migration that produced today’s cultural entanglements. Indigenous people, scholars, and artists appear amid books, maps, gears, compasses, and targets—symbols of knowledge production, power, extraction, and the retelling of history from subaltern perspectives. The overall composition highlights hybridity, language politics, memory and trauma, and the creation of new identities across diaspora networks in a globalized world.

Table of Contents

Key Focus Areas in Postcolonial Cultural Studies

Postcolonial cultural studies examines how empires reorganized land, labor, language, faith, and feeling—and how colonized and diasporic communities made, broke, and remade those orders. The field combines theory with practice: archival recovery, repatriation policy, language revitalization, and design justice.

- Core questions: Who gets to speak, teach, and collect? What counts as evidence or heritage? How do hybrid cultures emerge under unequal conditions? What does repair look like—materially and emotionally?

- Approach: Interdisciplinary—history, anthropology, literary studies, museum studies, environmental humanities, media/tech studies.

- Scales: From intimate family memory to oceanic routes (Atlantic, Indian Ocean, Pacific) and planetary extractivism.

Hybridity & Cultural Mixing

Hybridity names identities, aesthetics, and institutions forged in colonial “contact zones.” It includes syncretism (religion/ritual), creolization (language/food/music), and vernacular modernities (local redesign of global forms).

Syncretic Religion & Ritual

- Latin America & Caribbean: Santería, Candomblé, Vodou—Catholic saints mapped onto Yoruba/Lucumí or Kongo deities; feast days align with agricultural calendars.

- Philippines: Catholicism interwoven with precolonial anito spirit veneration and processional theater.

- East Africa–Indian Ocean: Swahili Islam braids mercantile etiquette, poetry (utendi), and Sufi orders with local matrilineal customs.

Creole Languages, Foods & Music

- Haitian Creole, Tok Pisin, Krio; culinary creoles (jollof → diaspora rice lines; vindaloo; feijoada).

- Afro-Atlantic music lineages: work songs → blues → jazz → hip hop; Afro-Brazilian samba; Indo-Caribbean chutney soca.

Architecture & Urban Forms

- Indo-Saracenic civic buildings; Andean Baroque façades with Quechua iconography; Swahili coral-rag houses with Omani courtyards.

Literature & Narrative Hybrids

- Achebe, Dangarembga, Rushdie, Mo Yan, Alexis Wright: oral cadence + European novel; code-switching as world-building.

- Key debate: Hybridity as creativity vs. as euphemism that can blur coercion and loss.

Resistance: Cultural, Political, Artistic

Resistance spans quiet persistence (language, dress, farming) to mass politics and aesthetic rupture.

Everyday & Cultural Resistance

- Kōhanga Reo (Māori language nests), Hawaiian language immersion, Sámi yoik revival.

- Food sovereignty: milpa systems, seed banks, and quilombola/Maroon agro-forestry.

Anti-Colonial Movements

- Gandhi’s swadeshi and Salt March; Algerian FLN media networks; Pan-African congresses; Indonesian underground presses.

- Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s shift to Gikuyu theatre; Black Consciousness (Biko) and poetry as political education.

Artistic Resistance & Third Cinema

- Fanon on colonial psychology; Sembène’s Camp de Thiaroye; Solanas/Getino’s “cine-acto” manifestos.

- Calypso, reggae, rai, and Afrobeat as satirical counter-publics.

Cultural Appropriation, Restitution & Intellectual Property

This section treats appropriation as a power relation: the taking or re-use of cultural expressions, knowledge, images, or remains without free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC), proper context, or fair benefit to source communities. Postcolonial repair combines law, museum practice, design ethics, and community governance.

Key Terms & Distinctions

- Appropriation – extraction or commercialization of cultural elements without consent/credit/benefit.

- Appreciation – respectful engagement with communities: co-design, attribution, payment, and agreed protocols.

- Misuse – use of sacred/ceremonial items (e.g., regalia, funeral images) outside permitted contexts.

- Biocultural knowledge (BCK) – traditional ecological knowledge, seeds, medicines, motifs linked to place and kinship.

Colonial Seizure & Display

- War plunder and “expeditions” moved Benin Bronzes, Parthenon/Elgin marbles, and thousands of objects to imperial museums.

- Human remains and so-called ethnographic collections were catalogued as science, denying personhood and living ties.

- Exhibitions and world fairs exoticized living peoples, fixing stereotypes that still shape tourism and media.

Contemporary Extraction Patterns

- Fashion & lifestyle: copying Indigenous motifs; sacred headdresses worn at festivals; “tribal” prints without attribution.

- Music & film: sampling field recordings or chants without clearance; remixing “world music” minus royalties.

- Design & tattoos: commercializing clan designs or tatau/moko patterns reserved for specific lineages.

- Food & wellness: trademarking traditional recipes/herbal knowledge; spiritual retreats selling restricted ceremonies.

- Digital/AI: training datasets scrape Indigenous art styles and community photos; “style transfer” models mimic sacred designs; metadata stripping erases authorship.

Law & Policy Frameworks (What Exists, What’s Missing)

- UNDRIP (UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples): FPIC; cultural and intellectual property rights.

- NAGPRA (U.S.): repatriation of human remains and sacred objects to Tribes and Native Hawaiian Organizations.

- UNESCO 1970 Convention & UNIDROIT 1995: combat illicit export and mandate return of stolen cultural property.

- UNESCO 2003 Convention: safeguarding intangible cultural heritage (language, ritual, craft skills).

- CBD/Nagoya Protocol: access and benefit-sharing for genetic resources and associated traditional knowledge.

- WIPO IGC (ongoing): toward international protection for Traditional Knowledge (TK) & Traditional Cultural Expressions (TCEs).

- Gaps: many designs/rituals are communal and timeless—poorly served by standard IP (copyright/patent/trademark) designed for individual authors & short terms.

Illustrative Case Studies

- Benin Bronzes: provenance research led to returns and long-term loans; new Edo Museum projects prioritize Nigerian curatorship and community access.

- Navajo Nation v. Retailer: misuse of the “Navajo” name on clothing/liquor goods resulted in settlement and licensing reforms.

- Hopi Sacred Items in France: community advocacy halted sales; some items returned via private purchase and donation.

- Māori Taonga: iwi-led negotiations have repatriated remains and taonga; museum digitization follows access protocols (gender/season/sacred status).

- AI Art “Style” Models: Indigenous artists documented scraping of their work; advocates now push consent-based datasets and TK-aligned licenses.

Repair Tools & Shared Governance

- Provenance research and open ledgers linking objects to collectors, routes, and descendants.

- Repatriation pathways: full return, long-term loan under community authority, or shared stewardship with veto rights.

- Community protocols: who may see, touch, record, or perform; seasonal/gendered restrictions; language-first description.

- Benefit-sharing & funds: royalties, co-ownership, apprenticeships, craft cooperatives, and local cultural trusts.

- Digital returns: high-resolution files, 3D scans, and knowledge records deposited with community archives; controlled access for sensitive materials.

- Indigenous Data Sovereignty: CARE Principles (Collective Benefit, Authority to Control, Responsibility, Ethics); local data repositories.

- Labeling & notices: Traditional Knowledge (TK) and Biocultural (BC) Labels signal permissions, attribution, and community protocols alongside or beyond Creative Commons.

Ethical Practice: A Due-Diligence Checklist

- Map stakeholders: identify community custodians, not just “country of origin.”

- Seek FPIC: free, prior, and informed consent—documented and ongoing.

- Co-design & credit: invite community designers/reviewers; name makers and knowledge holders.

- Pay fairly: budgets include licensing fees, royalties, and community funds.

- Respect protocols: avoid sacred/restricted motifs; confirm what is public versus restricted knowledge.

- Provenance audit: verify acquisition histories; publish findings.

- License clearly: use TK/BC Labels or community licenses that specify allowed uses and care obligations.

- Design for access: language-first metadata; community veto rights over display and marketing.

- Plan for returns: include repatriation/loan clauses and disaster-recovery for digital files.

- Evaluate impact: annual review with community; adjust practice and profit-sharing as needed.

Quick Guides by Sector

- Museums/Archives: community advisory boards; reparative description; culturally appropriate access rooms; climate-safe return logistics.

- Fashion/Design: sacred/off-limits lists; co-ownership of patterns; traceable supply chains; story labels naming artists and places.

- Media/Music: sample clearance from performers and communities; revenue splits; context notes in liner credits and platforms.

- Tech/AI: consent-based datasets; opt-out/opt-in registries; geofenced models; watermarking; dataset nutrition labels that disclose sources and restrictions.

Teach & Apply

- Studio brief: redesign a product that currently appropriates a motif; deliver a co-authored license, revenue model, and protocol sheet.

- Policy memo: draft a 1-page museum restitution roadmap for one object (timeline, partners, shipping, legal basis, care on return).

- Platform audit: test an AI image model with TK-labeled prompts; record refusal/consent behavior and propose guardrails.

Representation: From Stereotypes to Self-Authorship

Colonial media did not merely “depict” the world; it produced racial knowledge—organizing who could be seen, heard, or believed. Postcolonial and Indigenous makers counter this by asserting story sovereignty, community protocols, and new distribution infrastructures.

Colonial Optics: How Empire Made Images & Facts

- Ethnographic staging: studio portraits, anthropometric photography, and postcard series posing “types” and “tribes.”

- Science as spectacle: phrenology and race taxonomies; human displays at world fairs; museum dioramas that froze peoples “out of time.”

- Travel writing & maps: explorer journals, missionary presses, and Mercator projections that centered Europe and shrank the Global South.

- Early mass media: Kipling-era “civilizing mission,” Orientalist opera/painting, and Hollywood casting that rendered the East as sensual/menacing (“exotic,” “savage,” “noble”).

- Sound archives: gramophone “collecting” of songs without consent; field recordings circulated as ownerless data.

Stereotype Catalogue (to identify & avoid)

- “Vanishing native,” “noble savage,” “hypersexualized harem,” “terrorist,” “eternal peasant,” “witch doctor,” “model minority.”

- Visual codes: perpetual war zones, safari palettes, poverty porn, nameless crowds; English voiceovers that overwrite local speech.

- Industry habits: white savior plotlines, brownface/blackface, generic “tribal” music, token expert panels.

Platform Logics & Algorithmic Bias

- Visibility: recommendation systems favor dominant-language content; subtitle economics shape what travels.

- Moderation: uneven policy enforcement suppresses testimonies in low-resource languages; cultural speech flagged as “hate” out of context.

- AI training: datasets scrape Indigenous art, ritual images, and community photos; auto-translation flattens kinship terms and honorifics.

- Repair: consent-based datasets, local-language subtitling funds, algorithmic audits with community councils, and sensitive-content warnings designed with protocol.

Reclaiming Narratives & Story Sovereignty

- Third Cinema & Indigenous cinema: Sembène, Safi Faye, Haile Gerima, Warwick Thornton; collective authorship and location-based crews.

- Television & radio from below: Māori Television, Aboriginal Community Media, community FM in Latin America and the Sahel.

- Literary canons remade: Louise Erdrich, Witi Ihimaera, Alexis Pauline Gumbs; code-switching and oral archive citation in fiction and poetry.

- Popular industries: Nollywood’s local control of budgets/distribution; parallel cinema in India; Afro-Brazilian telenovela writers’ rooms.

- Digital counter-publics: Indigenous TikTok language lessons; diaspora podcasts; community-run archives with “right to opacity.”

Practice Standards for Ethical Representation

- FPIC first: obtain free, prior, informed consent from knowledge holders; confirm what is public vs. restricted.

- Co-authorship & credit: name elders, translators, and community researchers; credit oral sources as sources.

- Protocols in production: casting from community; language coaches; costume/prop clearance for sacred items; ceremony-safe filming rules.

- Metadata & labels: use Traditional Knowledge (TK) / Biocultural (BC) Labels; include local language names, place, and protocols in captions.

- Revenue & access: benefit-sharing agreements; community screenings first; subtitle/dub in local languages; archives with tiered access.

- Sensitivity review: engage cultural readers; run a “stereotype sweep” on scripts, music cues, posters, and marketing copy.

Studio & Classroom Activities

- Poster autopsy: deconstruct a colonial-era film poster; redesign with community credits, TK labels, and protocol notes.

- Subtitle lab: create two subtitle tracks (dominant vs. culturally faithful) and compare meaning loss; draft a subtitle ethics checklist.

- Dataset audit: review an image/LLM dataset for Indigenous or sacred content; propose consent removal or license terms.

- Distribution plan: map a community-first release (local premiere, radio cut, dubbed reels, offline kits for low bandwidth).

Desired Outcomes

- Shift from extraction to collaboration; from token visibility to control over narrative, metadata, and money.

- More multilingual, locally-credited catalogs and platforms; fewer harmful tropes; durable infrastructures for self-authorship.

Language Politics & Translation

Empire reorders languages—elevating some as administrative lingua francas while suppressing others as “dialects.” Postcolonial projects reverse that hierarchy through revival, official recognition, and translation justice: returning control of words, names, and meanings to the people who hold them.

Hierarchies, Standardization & Nation-Building

- Colonial lingua francas: English, French, Portuguese used for law, trade, schooling.

- Standardization politics: “one nation, one language” policies marginalize regional tongues; spelling/orthography reforms can both empower and exclude.

- Case studies:

- Kiswahili in Tanzania as inclusive nation-language; media quotas build vocabulary in science and politics.

- te reo Māori revival (Aotearoa/New Zealand): kōhanga reo (language nests), kura kaupapa Māori, Māori Television, official status, and naming authorities.

- Irish/Welsh signage laws and broadcasting (TG4/S4C) expand public presence; Quechua/Aymara/Guaraní co-official status in parts of the Andes and Paraguay.

- South Africa: eleven official languages, but resourcing/translation capacity determines real access.

Language, Law & Public Services

- Due process: court interpretation quality affects justice outcomes; technical terms (land, kinship, consent) need agreed glossaries.

- Schooling: mother-tongue education improves attainment; transition models (L1 literacy → L2 academic) require teacher training and materials.

- Health & migration: trauma-informed interpreting; informed consent forms localized beyond literal translation.

Code-Switching & Translanguaging

- Code-switching: shifting between languages/registers to signal identity, safety, or emphasis (courts, classrooms, hip hop, sermons).

- Translanguaging: using all linguistic resources at once (speech + text + gesture) as valid pedagogy and art, not “broken language.”

- Creoles & pidgins: recognition as full languages (Haitian Creole, Tok Pisin, Krio) with literature and media, not “simplified speech.”

Translation Theory, Power & Ethics

- Domestication vs. foreignization (Venuti): smooth for target readers vs. preserve source texture; postcolonial contexts often favor visibility of difference.

- Skopos (purpose): legal, ritual, and poetic texts require different choices about literalness and annotation.

- Spivak’s warning: translation can be epistemic violence if it erases subaltern voice; use community co-translation and paratexts (glossaries, translator’s notes).

- Attribution & pay: list translators, cultural advisors, and interpreters as co-authors; budget for iterative review and community rights to withdraw.

Subtitling, Dubbing & Media Circulation

- Subtitle economics: low budgets = loss of nuance; invest in community subtitlers for kinship terms, politeness levels, song/chant translation.

- Dubbing politics: voice casting across accents and social registers; avoid “neutral Spanish/Arabic/English” that erases local identity.

- Fansubs & community captions: rapid circulation but variable quality; adopt review pipelines and credit contributors.

- Accessibility: SDH (subtitles for the deaf and hard-of-hearing) and audio description in Indigenous/vernacular languages expand audiences.

Toponyms, Names & Linguistic Landscapes

- Renaming & dual naming: restore Indigenous place names (e.g., Uluru / Ayers Rock; Aotearoa / New Zealand proposals).

- Linguistic landscape: street signs, clinics, courts, transport—visibility signals belonging; font support and Unicode coverage matter.

- Personal names: identity documents must accept diacritics and naming conventions outside Western first/last structures.

Digital Infrastructures, Unicode & AI

- Scripts & keyboards: full Unicode support, input methods, OCR for historical scripts, fonts for diacritics (e.g., Vietnamese, Yoruba).

- Low-resource languages: ASR/TTS and MT (machine translation) underperform; invest in community corpora with consent and benefits.

- Dataset governance: community-owned text/audio datasets; opt-in/opt-out registries; model cards disclosing language coverage and risks.

- Platform policy: moderation and safety teams in local languages; escalation paths with community councils.

Rights & Frameworks

- UNDRIP: language rights, FPIC (Free, Prior, Informed Consent).

- European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages; Official Languages Acts (various countries).

- Education policies: mother-tongue instruction mandates; teacher training and textbook localization.

Translation Justice: Practical Checklist

- Co-create glossaries with knowledge holders (land tenure, kinship, spiritual terms) and publish them with attribution.

- FPIC pipeline: consent → draft translation → community review → approvals; document what stays un-translated.

- Respect opacity: some words/songs should not circulate; mark them as restricted rather than forcing equivalence.

- Credit & pay translators, interpreters, and cultural readers; include residuals for re-use.

- Paratexts matter: translator’s notes, pronunciation guides, audio clips; choose footnotes vs. in-line based on audience.

- Test with users: comprehension checks with elders, youth, and new speakers; revise timing for subtitles and readability for signage.

Mini-Labs (Class/Studio)

- Kinship Lab (30 min): translate 10 kinship terms into a colonial language; annotate losses; propose UI patterns (hover notes, audio).

- Courtroom Script (45 min): rewrite a legal notice into two local languages; co-create a pictorial version for low-literacy contexts.

- Subtitles Sprint (40 min): produce SDH subtitles in a vernacular; include song translation and speaker IDs; peer-review for cultural fidelity.

- Dataset Audit (60 min): inspect an MT/ASR training set for community consent and balance; draft a remediation plan and data-sharing terms.

Memory, Trauma & Repair

Colonialism produced not only material dispossession but also mnemonic damage—silences, shame, and fragmented archives. Postcolonial memory work therefore pairs historical evidence with care practices: truth-telling, ritual, language revival, land return, and community-controlled archives. The goal is not closure but continuing repair.

Key Concepts & Frameworks

- Cultural memory: how communities remember through ritual, place, and media (songs, carvings, quilts, murals).

- Trauma & postmemory: harms carried across generations via stories, silence, and bodies (epigenetic and social pathways).

- Mnemonic justice: fair recognition in archives, museums, curricula, and public space; the right to remember and to withhold.

- Care ethics: memory-making as relational labor (consent, reciprocity, survivor leadership).

Landscapes of Memory (Contested Sites)

- Plantations & mines: tours designed with descendant communities; memorial gardens for enslaved/indentured workers; wage and mortality ledgers digitized with context warnings.

- Missions & schools: Residential/boarding school cemeteries; language classrooms built on former school grounds; survivor-designed exhibits.

- Ports & oceanic routes: slave forts, indenture depots, and shipwrecks; underwater memorials, diaspora regattas, and sonic installations.

- Museums & archives: provenance walls; repatriation galleries; reading rooms for sensitive collections with culturally appropriate access protocols.

- Digital spaces: counter-memorial websites; 3D reconstructions; AR wayfinding that restores erased place-names.

Truth Processes & Public Inquiries

- South Africa TRC: amnesty-for-truth model; community hearings broadcast in multiple languages.

- Residential Schools (Canada/Australia): survivor testimony, archives of forced removals, language and land commitments.

- Local truth projects: city-level commissions on policing, monuments, and redlining; church & university reckonings with slavery and empire.

- Design principles: survivor-led agendas; trauma-informed facilitation; multilingual access; independent archival deposit; follow-up reparations plan.

Reparations, Restitution & Policy

- Material reparations: land return/long leases; scholarship endowments; health and housing funds; revenue shares from heritage sites.

- Cultural restitution: repatriation of remains and sacred objects; long-term loans under community authority; co-curation accorded veto powers.

- Symbolic repair: apologies, renamings, commemorative days; curriculum changes; memorial scholarships.

- Monitoring: independent boards including youth and elders; public dashboards tracking commitments and timelines.

Healing Practices & Community Care

- Language immersion: kōhanga reo, master–apprentice programs, immersion camps; lexicon projects for ceremony and everyday life.

- Ritual & arts: commemorative walks, quilting and carving circles, songlines mapping, dance/theatre testimony (“verbatim theatre”).

- Clinics & counseling: trauma-informed services in local languages; cultural safety training for health workers; grief groups with elders.

- Youth programs: oral-history filmmaking, podcasting, VR remembrance built with local designers; intergenerational mentorship.

Archives, Data & Consent

- Community control: Indigenous Data Sovereignty; CARE Principles (Collective Benefit, Authority to Control, Responsibility, Ethics).

- Sensitive materials: TK/BC Labels indicating restricted, seasonal, or gendered access; right to opacity (Glissant).

- Digitization with dignity: content warnings; co-authored descriptions; audio name-pronunciations; offline kits for low bandwidth.

- Redress ledgers: open, searchable ledgers linking objects/land parcels to claims, testimonies, and decisions.

Design Principles for Memorials & Exhibits

- Survivor leadership: steering committee with decision power; paid roles for community researchers and artists.

- Situatedness: site-specific interpretation (soil, water, sound) rather than abstract displays detached from place.

- Multimodality: text + audio in local languages; tactile and scent elements; quiet rooms for reflection.

- Ongoingness: spaces for updates, new names, and community contributions; anniversaries and seasonal rites built in.

Case Snapshots (Comparative)

- Maroon & quilombola memory (Americas): land-title recognition paired with festivals and school curricula co-written with elders.

- Indian Ocean indenture: depot museums linking Mauritius, Fiji, Guyana; ship-list databases enabling family reconnection.

- Pacific nuclear testing: medical archives opened with consent; compensation funds; memorial canoes crossing test atolls.

- Urban empire: port city trails marking segregated quarters, consulates, and strike sites; street renamings with QR-linked oral histories.

Teaching & Studio Labs

- Memory Map (90 min): co-create a map of local colonial sites; attach a 100–150 word card (history, present use, community ask).

- Testimony Ethics (60 min): draft a consent form for oral histories (withdrawal, sensitivity flags, access levels); role-play interviewer/interviewee.

- Archive Repair (2 h): choose one catalog record; add community names, language terms, pronunciation audio; apply a TK Label and rationale.

- Design a Counter-Monument (2 h): low-fi prototype balancing truth, care, and access; include a budget and maintenance plan.

Implementation Roadmap (Institutions)

- Audit collections/sites for colonial provenance and sensitive materials; publish summary.

- Covenant with communities: FPIC, hiring targets, honoraria scales, decision rights, and timelines.

- Act: initiate returns/loans; redesign exhibits; fund language and youth programs tied to the site.

- Account: independent oversight; annual public report; adaptive commitments with community sign-off.

Empire, Land & Extractivism

Colonial rule remapped ownership, labor, and life itself. Plantations, mines, railways, and “fortress” conservation replaced reciprocal stewardship with extractive frontiers. These legacies persist as land grabs, toxic “sacrifice zones,” and climate risk concentrated in communities least responsible for emissions. Postcolonial environmentalism links ecological repair to sovereignty, livelihood, and knowledge justice.

Key Concepts & Timelines

- Terra nullius & enclosure: legal fictions that erased Indigenous title and communal tenure; cadastral mapping to tax, police, and sell land.

- Plantationocene: monocrop regimes (sugar, rubber, tea, coffee, cotton, palm) reorganized soils, diets, pathogens, and kinship.

- Extractivism: a mode of accumulation (oil, gold, tin, cobalt, lithium, rare earths) that treats land as a commodity, labor as disposable, and waste as externality.

- Fortress conservation: parks without people—dispossession by “nature protection”; contemporary “green grabbing.”

- Blue economy: maritime zoning, industrial fishing, and seabed mining with uneven benefits and risks to small-scale fishers.

Colonial Infrastructures & Ecological Change

- Plantations: enslaved and indentured labor; soil exhaustion; invasive species; mosquito ecologies and disease (malaria, yellow fever).

- Mining frontiers: pit and riverine mining, mercury/cyanide contamination; rail/port corridors built for export, not local mobility.

- Hydropower & dams: colonial/Cold War projects flooded villages and sacred sites; sediment trapping, fisheries collapse.

- Botanical empires: Kew, Calcutta, and Peradeniya gardens moved seeds globally; “acclimatization” societies and bioprospecting.

- Mapping & measurement: cadastral surveys, forest inventories, yield tables—technics that still gatekeep access and compensation.

Contemporary Frontiers & Unequal Burdens

- Oil & gas: flaring, spills (e.g., Niger Delta), security violence; revenue enclaves with little local reinvestment.

- Critical minerals: cobalt and copper (DRC/Zambia), lithium (South American salt flats), rare earths (East/Southern Africa, China-linked projects).

- Toxic colonialism: e-waste dumps, shipbreaking beaches, pesticide trade; “sacrifice zones” near refineries and ports.

- Climate injustice: highest exposure to droughts, floods, cyclones; limited adaptation finance and insurance penetration.

Comparative Case Snapshots

- Niger Delta (Nigeria): oil spills and gas flaring harm fisheries and farms; community litigation, youth movements, and clean-up funds demand accountability.

- Yasuní (Ecuador): biodiversity vs. oil; national referendum and rights-of-nature constitution frame keep-it-in-the-ground campaigns.

- Whanganui River (Aotearoa/NZ): legal personhood recognizes river as ancestor; co-governance by iwi and Crown shapes restoration and consent.

- Maasai & fortress conservation (East Africa): eviction pressures around reserves; community conservancies, benefit-sharing, and land trusts as alternatives.

- Indian coal belt: Adivasi forest rights under the Forest Rights Act; conflicts among mining, elephants, and community agroforestry.

- Pacific atolls: sea-level rise and nuclear test legacies; relocation with cultural continuity, ocean commons claims, and memory justice.

Policy, Rights & Climate Finance

- UNDRIP & FPIC: Free, Prior, Informed Consent for projects on Indigenous lands; community veto rights in practice, not just on paper.

- Land & water tenure reform: recognize customary title; communal and seasonal rights; women’s land rights and inheritance.

- REDD+ & carbon markets: risk of “carbon colonialism” if carbon rights bypass communities; ensure equitable revenue sharing and monitoring by locals.

- Loss & Damage: climate compensation for irreversible harms; accessible funds for small communities, not just states.

- Debt-for-nature swaps: tie relief to locally led conservation with livelihood guarantees; transparent governance to avoid new dependency.

- Rights of Nature & personhood: rivers/forests recognized as legal subjects; guardianship councils with Indigenous majority.

Stewardship Knowledge & Practice

- Cultural burning & fire stewardship: mosaic burns reduce megafires and restore habitats (Australia, California, Amazon headwaters).

- Agroecology & food sovereignty: milpa systems, terraced farming, zai pits, mangrove-pond aquaculture; seed sovereignty networks.

- Community-led monitoring: ranger programs, drone and acoustic monitoring with local data control; youth science brigades.

- Biocultural protocols: local rules for access to sacred sites, medicinal plants, and knowledge; TK/BC Labels on digital collections.

Design Principles for Just Transitions

- Sovereignty first: recognize land/water title and decision rights before permitting.

- FPIC as a process, not a checkbox: multilingual, iterative, with power to say no; public documentation.

- Benefit-sharing: royalties, equity stakes, local hiring, and long-term funds managed by communities.

- No net dispossession: conservation must increase—not reduce—secure access to livelihoods and culture.

- Data justice: community-owned maps, baselines, and monitoring; open dashboards for budgets and impacts.

- Exit & remediation plans: mine closure funds, tailings safety, reforestation with native species, cultural site restoration.

Teaching & Studio Labs

- Commodity Chain Map (90 min): trace sugar/rubber/palm/cobalt from extraction to shelf. Add labor regimes, emissions, and waste streams; propose one leverage point for justice.

- FPIC Simulation (60 min): role-play a lithium project: community council, company, state, independent scientists; draft a consent agreement with veto, revenue, and monitoring clauses.

- Carbon Contract Audit (60 min): analyze a REDD+/offset project: who owns the carbon? who monitors? who gets paid? write a 300-word equity review.

- Counter-Conservation Design (2 h): redesign a park plan to include grazing, ceremony, and seasonal harvest; produce a zoning map and governance board charter.

Quick Glossary

- FPIC: Free, Prior, Informed Consent—community decision-making power before any project.

- Green grabbing: land appropriation justified by conservation or carbon projects.

- Sacrifice zone: place bearing disproportionate pollution/risks for others’ benefit.

- Bioprospecting: extracting medicinal/seed knowledge, often without benefit-sharing.

- Just transition: decarbonization that secures jobs, health, and rights for affected workers and communities.

Urban Space, Heritage & Tourism

Empire reshaped cities with extractive logistics (ports, railheads), military geographies (cantonments, forts), and racialized zoning. Postcolonial urbanism negotiates these legacies through renaming, monument debates, housing justice, and heritage economies—from cruise tourism and short-lets to community-led curation and benefit-sharing.

Colonial Urban Form: Plans, Belts & Infrastructures

- Street plans: export-oriented grids linking ports, custom houses, and warehouses; axial boulevards for parades and surveillance.

- Cantonments & hill stations: sanitary separation of officials/soldiers; climate enclaves with imported architectural styles.

- Segregation belts: “native” vs. “European” towns; racial bylaws, curfews, and building codes that still map onto service access.

- Infrastructure lock-ins: rail alignments, drains, and flood defenses sized for colonial cores, under-serving peri-urban settlements.

Memory Politics: Naming, Monuments & Counter-Sites

- Renaming: streets, squares, and stations reflect language and sovereignty shifts; dual-naming honors layered histories.

- Monument debates: remove, re-contextualize, or counter-monument? Options include explanatory plinths, relocations to study centers, or new works that “talk back.”

- Sites of conscience: prisons, plantations, cantonments curated with survivor/descendant leadership and multilingual interpretation.

Heritage Economies: Value, Risk & Redistribution

- Tourism boosts: conservation jobs, crafts, festivals, adaptive reuse (markets, libraries, schools) within historic fabrics.

- Risks: “museumification,” resident displacement, noise/traffic, short-let conversion, souvenirization of sacred spaces.

- Cruise & day-trip pressures: seasonal crowding, waste spikes, waterfront privatization; thin local capture of spending.

- Short-term rentals: loss of long-term housing; price shocks in “old quarters”; cultural performance timed to visitor flows.

Community-Led Curation & Governance

- Heritage committees: neighborhood councils with veto on uses, signage, hours, and festival routes.

- Story stewardship: resident-authored trails, oral history plaques, QR codes linking to local archives in vernacular languages.

- Benefit-sharing: ticket/film permit levies into a local fund for repairs, scholarships, and small-business grants.

- Access protocols: sacred/seasonal restrictions; attire guidance; “no photography” zones with respectful alternatives.

Housing, Livelihoods & the Right to the City

- Anti-displacement tools: rent caps, right-to-return after restoration, community land trusts, limited-equity co-ops.

- Street economies: designated vending streets/markets with storage, shade, water, and sanitation; vendor representation in planning.

- Inclusive access: step-free routes, tactile maps, local-language wayfinding, prayer rooms, child-friendly spaces.

Conservation & Adaptive Reuse

- Repair over replacement; reuse colonial shells for schools/libraries; green retrofits (passive cooling, rain harvesting) that keep façades and street rhythms.

- Materials justice: source local crafts (lime plasters, timber joinery) with apprenticeships for youth.

- Design guidelines: frontage transparency, height transitions, night-lighting that respects residents and wildlife, sign/awning codes that protect sightlines and languages.

Metrics & Monitoring (Track What Matters)

- Resident mix (% long-term vs. short-let), school enrollments, median rents vs. median wages.

- Footfall by hour/season; peak crowding at sacred sites; modal split (walk/cycle/transit).

- Small-business survival; % procurement from local firms/co-ops; craft apprenticeship numbers.

- Noise, particulate, waste per visitor; water/energy use in heritage buildings.

Comparative Case Snapshots

- Old Quarters (Urban Europe/Med): café culture + short-lets → resident flight; cities trial tourist caps, “quiet hours,” and neighborhood funds.

- Port Cities (Africa/Indian Ocean): Swahili stone towns balance dhow heritage, mosque soundscapes, and cruise-ship day peaks via timed tickets and prayer-time buffers.

- Temple/ghat districts (South Asia): sacred viewshed rules, waste-free rituals, and vendor cooperatives; festival calendars co-managed with priests and residents.

- Latin American centers: barrios patrimoniales with social housing + cultural passes for locals; murals narrate anti-colonial histories.

- Pacific towns: bilingual signage and Indigenous toponyms; marae/meeting-house protocols embedded in event permits.

Policy Toolkit: From Extractive Tourism to Care-Centered Heritage

- Zoning & caps: limit short-term rentals; ban hotel conversions in residential lanes; require ground-floor active local uses.

- Pricing & permits: dynamic pricing for peak sites; film/photo permits with community escorts and fees to local funds.

- Mobility plan: pedestrianize at peak; resident access windows; low-emission deliveries; night bus loops for workers.

- Procurement & training: % local procurement for tours/signage/catering; certify guides in language/history/etiquette; craft apprenticeships.

- Governance: neighborhood heritage boards with resident quotas; open dashboards for metrics and budgets; annual assemblies to adjust rules.

Classroom & Studio Labs

- Heritage Walk (90 min): map three colonial traces; draft a 120-word plaque for each with a resident quote and a protocol note.

- Short-Let Impact (60 min): sample listings; estimate lost long-term units; propose a cap + enforcement and a right-to-return scheme.

- Counter-Monument (2 h): low-fi prototype that juxtaposes official and community memory; include maintenance and education plan.

- Wayfinding Sprint (45 min): design bilingual signs and quiet-route maps; add icons for prayer, water, restrooms, and step-free paths.

Digital Postcoloniality & Platforms

The digital sphere reproduces—and can also repair—imperial patterns. Cloud regions, app stores, datasets, and moderation rules decide who gets seen, tracked, paid, or silenced. Postcolonial digital work pairs infrastructure justice with language equity, data rights, and community-owned networks.

Core Concepts

- Data colonialism: extraction and enclosure of people’s behavioral data and community knowledge as proprietary assets.

- Compute colonialism: AI advantages flow to actors with capital, chips, energy, and data centers—often outside source communities.

- Platform power: app stores, ad exchanges, and payment rails act as chokepoints that set rents and rules for local creators.

Infrastructures & Geopolitics

- Subsea cables & IXPs: landing points determine latency, price, and sovereignty; regional internet exchanges reduce costs and surveillance exposure.

- Cloud regions & energy: data residency, carbon intensity, and water use; who decides where models are hosted and who can access compute?

- Spectrum & zero-rating: pricing and “free” bundles shape information diets; need net-neutrality and public-interest carriage rules.

Language & Information Equity

- Low-resource languages: ASR/TTS/MT lag; invest in community corpora, orthography support, fonts/IME, OCR for historical scripts.

- Search & ranking bias: dominant-language pages outrank local sources; subtitle scarcity limits film/news reach.

- Community translation funds: pay local subtitlers and fact-checkers; build shared glossaries for law, health, climate.

AI, Datasets & Consent

- Dataset provenance: scrapings of Indigenous art, ritual images, and oral histories require FPIC (Free, Prior, Informed Consent) and benefit-sharing.

- Model documentation: dataset nutrition labels; model cards disclosing language coverage, cultural risks, and refusal policies for sacred content.

- Guardrails: TK/BC labels respected at train and inference time; community opt-out/opt-in registries; geofenced models when required by protocol.

- Benchmarks: evaluate fairness in low-resource languages, code-switching, honorifics, and kinship terms—not just English metrics.

Moderation, Safety & Rights

- Coverage gap: under-resourced languages suffer over-removal (silenced testimonies) and under-removal (unchecked abuse).

- Context-aware rules: satire, ritual speech, and reclaimed slurs need cultural readers; escalation paths with community councils.

- Due process: notice, reasons, and appeal in local languages; transparency on automation vs. human review.

- Privacy & surveillance: SIM registration, spyware, and bulk monitoring chill speech; push for encryption, minimal data retention, and human-rights impact assessments.

Labor, Gig Work & Creator Economies

- Moderation labor: offshore moderators face trauma with low pay; require mental-health support, living wages, and collective bargaining.

- Gig platforms: algorithmic pay opacity, deactivation without appeal; demand data portability and worker-led councils.

- Creators: fair splits, localized payout rails, and discoverability quotas for minority languages/regions.

Digital Counter-Publics & Community Networks

- Hashtag publics: African, South Asian, and Indigenous campaigns documenting land, policing, and heritage—paired with offline assemblies.

- Mesh & community ISPs: locally maintained Wi-Fi meshes and shared backhaul; captive portals in local languages; disaster-resilient kits.

- FOSS stacks: open-source forums, wikis, and archiving tools with TK/BC-aware permissions and community governance.

Design Justice: Patterns that Work

- Localization by default: UI in local languages, script support, non-Latin search, calendar/number formats.

- Low-bandwidth modes: offline-first sync, text-first views, audio notes, image compression, and queueable uploads.

- Consent-forward UX: clear data uses, granular toggles, community auto-delete, and contextual “why we ask” prompts.

- Provenance & context: source cards for viral media; QR links to local archives; watermarking for official advisories.

- Accessibility: screen-reader support in local languages; voice interfaces tuned for dialects and code-switching.

Policy & Governance

- Data protection and cross-border flow rules that recognize community as a rights holder (not just the individual).

- Competition policy for app stores/ad markets; interoperability mandates; fair payment access for creators and small media.

- Public-interest obligations for very large platforms: researcher data access, independent audits, crisis protocols in local languages.

- Public investment: IXPs, community networks, language tech grants, and fellowships for local AI and safety teams.

Case Snapshots (Comparative)

- Indigenous TikTok & YouTube: language lessons and dance protocols reach youth; creator funds tied to community projects.

- Community mesh (LatAm/Africa): women-led networks with solar backhaul; local helpdesks and repair apprenticeships.

- Fact-check hubs (South Asia/Africa): WhatsApp hotlines, prebunk voice notes, and rumor dashboards in multiple scripts.

- Open cultural archives: TK/BC labels on song and image collections; tiered access and community curatorship.

Implementation Checklists & Studio Labs

- Dataset Due Diligence: provenance log, FPIC proof, TK/BC labels, language mix, and benefit-sharing plan.

- Moderation Equity Audit: coverage by language/region; false positive/negative rates; appeal outcomes; community reviewer council notes.

- Low-Bandwidth Redesign: ship an offline-first version of one feature; measure bandwidth and time saved.

- Subtitle Sprint: build a community subtitling pipeline for a public-health video in three local languages, with honorifics/kinship preserved.

- Mesh Pilot: plan a neighborhood network—sites, spectrum, budget, governance, and sustainability model.

Methods & Research Toolkit

- Archival & oral history: read colonial records against the grain; co-create oral archives with communities.

- Textual/visual analysis: discourse, paratexts, museum display critique, provenance studies.

- Ethnography & participatory methods: collaborative mapping, photovoice, story circles.

- Digital humanities: decolonial mapping, multilingual corpora, metadata repair.

Theoretical Foundations

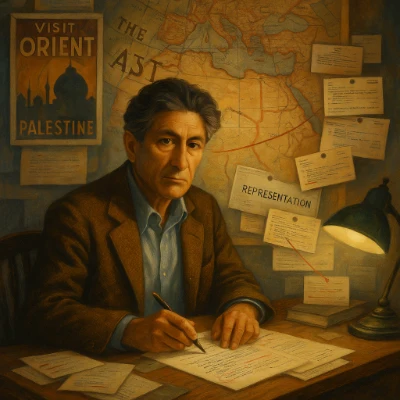

Edward Said

Concept: Half-library, half-map. Said stands at a desk strewn with marginalia; behind him, a palimpsest of 19th-century travel posters morphs into academic index cards, showing how representation manufactures the “Orient.” Cool inks and sepia overlays suggest archival critique; a thin red thread links image to footnote.

The composition places Said three-quarters profile beside a desk, pen poised over a page annotated with quotes and arrows. Behind him, lithographic posters labeled “The East” blur into catalog cards stamped with museum accession numbers, indicating knowledge/power. A library lamp casts a cone of light onto a framed word—representation—while a red thread stitches posters to books, visualizing citation as control. Muted blues and browns evoke archives; a window reveals a reverse map with Europe miniaturized, hinting at decentering the lens.

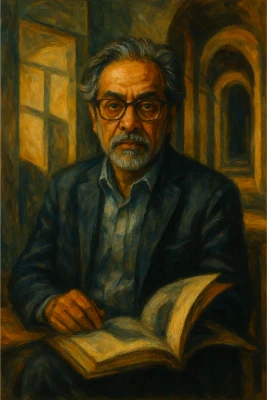

Homi K. Bhabha

Concept: A liminal corridor becomes a “third space.” Two architectural styles—colonial colonnade and modern glass—interpenetrate; Bhabha stands at the threshold as shadows echo, suggesting mimicry “almost the same but not quite.” Prismatic light fractures the floor into hybrid patterns.

Painted in warm ochres and deep indigos, Bhabha sits at a liminal threshold. On his left, a sunlit window casts soft rectangles of light; on his right, an arched passage recedes into layered shadow. The two planes don’t fully align, creating a seam—an intentional in-between where meanings are negotiated. His hand steadies an open book whose mirrored pages slightly misregister, hinting at mimicry’s slippage. The textured brushwork suggests palimpsest—ideas overwritten yet never erased—while the composition stages Bhabha’s argument that culture unfolds in contested interstices rather than fixed origins.

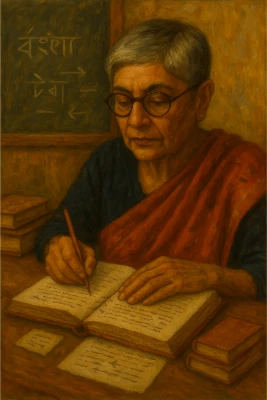

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak

Concept: A layered palimpsest of erased and rewritten lines. Spivak sits with a manuscript where certain passages are redacted; marginal notes reappear in the voices of women at the page’s edge. A folded megaphone rests beside her, symbolizing the problem of representation and “strategic essentialism.”

Painted in warm earths and deep blues, Spivak leans over an open notebook, pencil poised. The background is pared back: a chalkboard carries faint Bengali marks and bidirectional arrows—translation as negotiation rather than equivalence. On the desk, stacked books and marginal slips suggest archival labor; the absence of microphones or stage lights emphasizes study over spectacle. The composition keeps her gaze downward, honoring the ethics of careful reading and the right to opacity while evoking her lifelong attention to subaltern agency and the politics of representation.

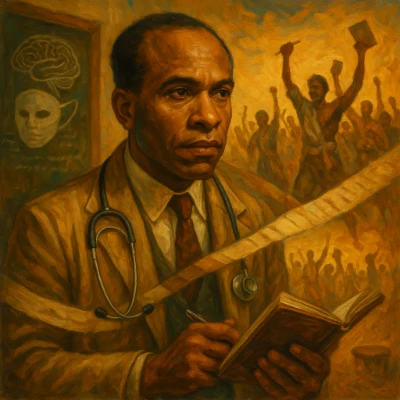

Frantz Fanon

Concept: Psychological and material decolonization. Fanon stands in a clinic doorway that opens onto a street of mass protest. One half of the scene shows clinical diagrams of face masks and nervous systems; the other shows a crowd shedding colonial uniforms. The palette flips from sterile green to urgent crimson and earth.

Stethoscope and notebook in hand, Fanon is rotated slightly toward a threshold. Behind him, chalkboard sketches of neural pathways and a face mask (alluding to Black Skin, White Masks); ahead, a crowd raises tools and books. A bandage motif unwraps across the canvas, revealing darker skin tones beneath a whitening powder. Dust lifts in warm light; a drum echoes at the horizon. The composition suggests healing as collective action as well as clinical insight.

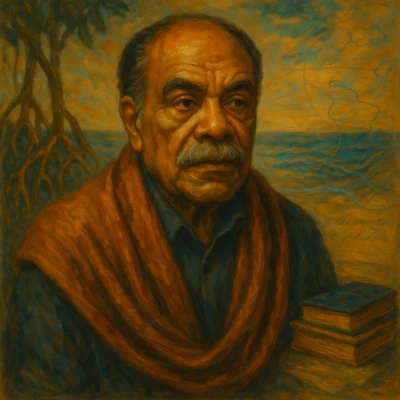

Édouard Glissant

Concept: Archipelagic relation. Glissant stands on a shoreline of mangroves; islands float like pages. Currents connect them with dotted lines that never fully resolve, honoring a “right to opacity.” The palette favors sea-greens and dusk violets; some forms remain beautifully unreadable.

Painted in warm earth and indigo tones, Glissant appears thoughtful and steady, his gaze set slightly past the viewer. A rust shawl frames a midnight-blue shirt, while the background weaves key motifs from his work: mangrove roots interlacing like communities in Relation, a calm sea meeting the sky, and faint, hand-drawn map lines that refuse to settle into borders. A small stack of books anchors the foreground. The brushwork remains textured and layered, echoing creolization’s braiding of languages and histories, and the soft shadows preserve his “opacity,” honoring the limits of what portraiture should reveal.

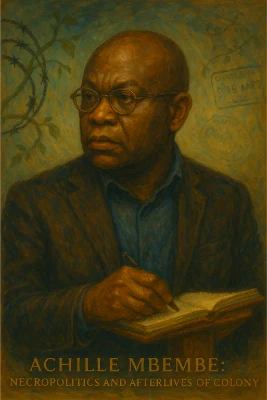

Achille Mbembe

Concept: Intimacies of the postcolony and necropolitics. Mbembe is seated at a table lit by a desk lamp; beyond the window sit a checkpoint and market. A ledger of budgets overlaps with silhouettes of everyday life, showing how sovereignty manages life and death. Cool graphite, with sharp highlights.

Rendered in warm ochres and indigo blues, Mbembe’s steady gaze sits just off-center, his hand poised over an open notebook. Around him, symbols of control dissolve: barbed wire softens into climbing vines; checkpoint stamps blur into indistinct circles; a dusk glow replaces the hard light of surveillance. The textured brushwork suggests archival layers—eras written over yet still legible—while the diagonal of his writing arm carries the eye from constraint toward growth. The portrait evokes Mbembe’s critiques of sovereignty and the management of life and death, and his insistence on imagining futures beyond the colonial grid.

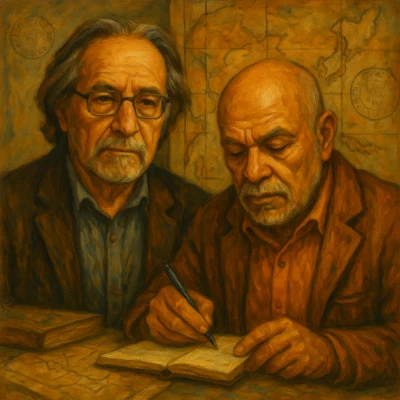

Walter Mignolo / Aníbal Quijano

Concept: Coloniality of power and epistemic delinking. Two desks face different horizons: one looks at a university façade overlaid with trade routes; the other at a community workshop. Between them, a loom weaves threads labeled “race/class/knowledge,” while scissors labeled “delink” cut a path for new designs.

In warm ochres and deep blues, the scholars appear side by side. On the left, Mignolo meets the gaze with a quiet, alert poise; on the right, Quijano leans over an open notebook, the pen mid-stroke. Behind them, a worn map bears ghosted trade routes and indistinct seals; lines fray and slip past the frame, suggesting knowledge that exceeds imperial grids. A stack of well-handled books anchors the foreground. The brushwork layers like palimpsest—notes over notes—evoking decolonial method: writing from the border, naming how power organizes race, labor, and knowledge, and sketching paths beyond it.

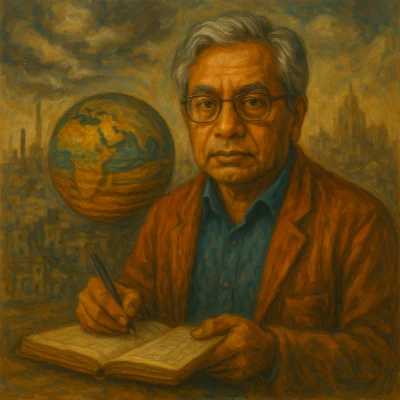

Dipesh Chakrabarty

Concept: Provincializing Europe and multiple temporalities. Chakrabarty stands by a timeline that branches like a delta: industrial time, agrarian cycles, sacred calendars, and planetary time (climate). Museum clocks show different tempos; footpaths weave from village to factory to glacier.

Painted in warm ochres and cool slate blues, Chakrabarty gazes calmly from the foreground, one hand steadying an archivist’s ledger while the other holds a pen mid-thought. The background fuses temporal scales: a smudged city skyline with factory stacks suggests modernity’s carbon age; above it, a suspended globe reveals concentric, stratigraphic bands—history meeting geologic time. Faint map lines of the Indian subcontinent drift across passing monsoon clouds. The textured brushwork layers like records in an archive, evoking his move from historicist narratives to the “planetary” frame, where human timescales and Earth systems entangle.

Examples in Postcolonial Cultural Studies

Postcolonial cultural studies tracks how communities negotiate empire’s afterlives—appropriating, remixing, resisting, and re-authoring meaning across religion, language, arts, law, heritage, and everyday life. Below are illustrative clusters with concrete cases and short notes on what each example shows (hybridity, creolization, subaltern voice, border thinking, repatriation ethics, and more).

Latin American Fusions

- Religious syncretism: Día de los Muertos blends pre-Hispanic ancestor veneration with Catholic All Souls’ rites; “Andean Virgins” (e.g., Virgen del Cerro/Potosí) depict Mary with Indigenous cosmologies (mountain/earth mother symbolism), revealing negotiation rather than simple conversion.

- Arts & architecture: Andean Baroque façades (Cusco, Potosí) carve flora/fauna and Inca iconography into Catholic churches, visualizing Indigenous agency within imperial aesthetics.

- Muralism and counter-history: Rivera, Orozco, Siqueiros narrate conquest, labor, and anti-imperial struggle on public walls—turning streets into people’s archives.

- Afro-Latin continuities: Candomblé and Santería ritual objects and rhythms (Bahia, Havana) reframe enslavement’s afterlives as living spiritual networks across the Atlantic.

- Language & law: Quechua/Aymara radio and bilingual education projects provincialize Spanish-only governance and reclaim community epistemologies.

South Asian Hybridity & Memory

- Partition memory cultures: Oral history archives, memorial museums, and graphic narratives (e.g., Train to Pakistan, Manto) assemble subaltern testimony against official nation scripts.

- Textile politics: Khadi, block-print, and indigo revival movements mobilize craft as anti-colonial economy and feminist labor history.

- Urban palimpsests: Colonial cantonments and railway towns re-zoned through bazaars, Sufi shrines, and informal settlements show how planning meets lived spatiality.

African Visual & Performance Worlds

- Photography and self-fashioning: Malick Sidibé and Seydou Keïta’s studio portraits stage modernity beyond colonial gazes, centering youth culture and autonomy.

- Performance & theater: Wole Soyinka and Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o rework classical forms with indigenous dramaturgies; community theaters use satire to critique extractive politics.

- Afrofuturist imaginaries: Visual arts, design, and music (from Sun Ra legacies to contemporary Lagos/Joburg scenes) project futures unbound from imperial time.

Caribbean Creolization

- Language: Haitian Kreyòl and Jamaican Patois literature elevate creole as intellectual medium, refusing the hierarchy of metropolitan French/English.

- Music & carnival: Calypso, reggae, soca, and steelpan transform plantation histories into diasporic sound archives and mobile classrooms.

- Poetics of Relation: Following Glissant, collaborative anthologies and multi-lingual performances stage opacity (the right not to be fully known) as ethics.

Indigenous Media and Land-Back

- Community film/radio: Māori, First Nations, and Andean collectives use media to record language, guardianship (kaitiakitanga), and treaty claims—counter-mapping colonial archives.

- Food sovereignty: Seed banks and traditional ecological knowledge projects (milpa, taro, bush foods) assert land stewardship against agri-extractivism.

- Ceremony as governance: Protocol-led gatherings and dances function as law in practice, not as “cultural add-ons.”

Literatures of Resistance

- Africa: Achebe’s Things Fall Apart exposes epistemic violence and narrative authority; Emecheta’s The Joys of Motherhood reframes gendered labor under colonial/urban capitalism.

- South Asia: Mahasweta Devi’s Imaginary Maps centers adivasi struggles, legal disenfranchisement, and counter-histories that unsettle development discourse.

- Caribbean: Walcott’s Omeros rewrites Homer through St. Lucian seas, fishing labor, and creole idiom—epic as island commons.

- Middle East & North Africa: Palestinian prison writings and women’s memoirs narrate statelessness, checkpoints, and everyday endurance.

- Settler colonies: Indigenous speculative fiction (e.g., Cherie Dimaline) reimagines futurity beyond extractive infrastructures.

Film, Music, and Digital Activism

- Third Cinema: Latin American and African collectives use non-commercial forms to mobilize audiences as co-producers of political meaning.

- Hip-hop & grime diasporas: From Dakar and Johannesburg to London, lyrics map borders, passports, policing, and joy as resistance.

- Hashtag publics: Transnational campaigns (e.g., anti-deportation, museum accountability) stitch local struggles into planetary networks.

Repatriation in Practice

- Benin Bronzes: Returns to Nigeria shape new models—provenance research, shared custodianship, and capacity building—beyond one-off shipments.

- Hawaiian iwi kūpuna (ancestral remains): Protocol-guided repatriations prioritize kinship relations, ceremonial care, and community authority over institutional timelines.

- Community-curated exhibitions: Power-sharing agreements, multilingual labels, and co-authored catalogs challenge the “neutral” museum voice.

- Data sovereignty: Digital surrogates, TK (Traditional Knowledge) labels, and access protocols ensure communities govern circulation of images and 3D scans.

Everyday Hybridity & Urban Life

- Street vernaculars: Code-switching signage, creole shop names, and multilingual memes provincialize monolingual policy.

- Relocation & remittance architectures: Diaspora funds remake housing and religious spaces, blending local craft with global materials.

- Culinary routes: Plantation crops (sugar, tea, cacao) re-enter kitchens as sites of critique and reparation—community kitchens, fair-trade co-ops.

Methods & Ethics in the Field

- Co-research: Projects designed with—not on—communities; benefit-sharing, open returns, and multilingual outputs.

- Opacity and care: Accepting limits to disclosure (Glissant’s “right to opacity”) as a research ethic, not an obstacle.

- Counter-mapping: Story maps and community atlases that replace extractive borders with kinship, watershed, and seasonal routes.

Applications of Postcolonial Cultural Studies

Postcolonial cultural studies offers practical tools for policy, design, teaching, and community action. Below are applied domains with concrete practices, decision frameworks, and evaluative metrics that translate theory—hybridity, coloniality, subaltern voice, Relation, opacity—into accountable change.

Cultural Policy & Preservation

- Language revitalization: community immersion schools; radio/podcast networks; orthography co-design; terminology banks for science and law; open licenses for teaching materials.

- Community archives: participatory description and metadata (name, kin, place); TK labels and access protocols; oral-history consent models recognizing collective custodianship; disaster-ready storage and digitization plans.

- Ethical heritage tourism: revenue-sharing MOUs; protocol guides for visitors; limits on photography and drone use; community-led narratives replacing extractive guidebooks.

- Cultural IP frameworks: benefit-sharing for designs, motifs, and botanical knowledge; defensive publications to prevent biopiracy; geographical indications for crafts.

- Museum restitution & repair: provenance and due-diligence pipelines; joint stewardship or rotating custody; capacity-building grants (conservation labs, training) in receiving communities; evaluation via community satisfaction, not only object counts.

- Urban heritage & zoning: protection of sacred sites and social infrastructure (markets, music yards); impact assessments that include intangible practices and night-time economies.

Social Justice & Equity

- Reparations portfolios: land return and co-management agreements; artifact returns with care funding; royalty schemes for cultural and scientific uses; debt cancellation tied to extractive histories.

- Land-back & stewardship: legal pluralism recognizing customary law; Indigenous ranger programs; carbon and biodiversity credits controlled by communities.

- Equity audits: supply-chain tracing for labor, dyes, and minerals in fashion and electronics; living-wage commitments; anti-racist editorial policies in media and publishing; transparent advancement data.

- Border & mobility justice: fee waivers and visa facilitation for artists/scholars at risk; legal support for stateless persons; portability of social protections for migrants.

- Health & environment: community-led monitoring of pollution around mines/ports; cumulative-impact standards; recognition of traditional healers within public-health outreach.

Education & Curriculum

- Canon expansion: pairing metropolitan texts with Indigenous, Afro-diasporic, and creole works; assignments that require citation beyond Global North publishers.

- Multilingual pedagogy: translanguaging classrooms; assessment that accepts answers across languages; glossaries co-authored with students and elders.

- Community co-teaching: honoraria and IP recognition for knowledge keepers; field classes hosted on country/territory with local protocols.

- Fieldwork ethics of reciprocity: return of data (audio, photos, transcripts); co-authorship where appropriate; research budgets that include community priorities (archiving, transport, childcare).

- Planetary perspectives: climate-humanities modules linking colonial energy histories to present risk; place-based mapping of extraction and resistance.

- Assessment redesign: reflective journals on standpoint; collaborative exhibits; public-facing briefs instead of only closed essays.

Media, Design & Tech

- Inclusive storytelling: hiring and pay equity in writers’ rooms; community review panels; consent-based use of vernaculars and sacred narratives; credits in local languages.

- Provenance & benefit-sharing for knowledge: design houses and game studios compensate source communities for motifs, songs, and narratives; contract clauses preventing distortion or sacred misuse.

- Dataset governance: document consent and collection contexts; remove colonial taxonomies; represent dialects and code-switching; audit for harms across translation, accent, and skin-tone variance.

- Responsible AI & UX: low-bandwidth, offline-first, and multilingual interfaces; privacy-by-default for at-risk users; community-switchable settings (name order, calendars, kin terms).

- Maps & platforms: co-designed cartography that includes Indigenous place names and no-go layers for sacred sites; data sovereignty hosting controlled by communities.

- Visual design ethics: avoid “exoticizing” palettes and tropes; co-create iconography; accessibility for low-vision, low-literacy, and screen-reader users.

Governance, Law & Institutions

- Participatory budgeting: cultural and youth councils allocate funds for festivals, archives, and language projects; transparent criteria foregrounding historically excluded groups.

- Legal reform: recognition of customary law and guardianship of rivers/forests; free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) embedded in permitting.

- Diplomacy & museums: bilateral agreements on restitution and touring; visas tailored for artists and researchers with flexible proof requirements.

Measurement & Accountability

- Equity KPIs: representation across seniority; pay-gap closure; share of budget to community partners; number of co-authored outputs.

- Cultural-impact metrics: language use in public services and classrooms; volume of returned objects and related care funding; visitor feedback on community-curated exhibits.

- Data ethics audits: dataset documentation completeness; model performance across dialects/skins; consent revocation pathways; harm-reporting responsiveness.

- Environmental justice indicators: reductions in exposure to pollutants around ports, mines, and refineries; restored access to water/land; biodiversity co-benefits.

In practice, these applications work best as processes rather than one-off projects: start with shared principles (consent, reciprocity, opacity, accountability), co-design with affected communities, and publish results and learnings in accessible formats and languages.

Why Study Postcolonial Cultural Studies

Postcolonial cultural studies equips you to read power in everyday life—how empire’s infrastructures of law, language, labor, land, and media reshape belonging, value, and voice. You learn to analyze hybrid cultural forms, repair archival gaps, and co-create futures with communities most affected by extractive histories.

Core Learning Outcomes

- Historical clarity: trace how conquest, slavery, indenture, and resource extraction built today’s borders, property regimes, and debt relations.

- Cultural fluency: interpret creolization, code-switching, and translation politics across diasporas without exoticizing or flattening difference.

- Power analysis: identify coloniality in contemporary policy (immigration, development, conservation) and propose alternatives grounded in community authority.

- Ethical practice: design research, policy, and products with consent, reciprocity, accessibility, and the right to opacity.

- Planetary frame: connect climate risk and energy histories to empire’s afterlives; read “local” problems alongside global supply chains.

- Communication for publics: translate scholarship into museum labels, policy briefs, podcasts, story maps, and community exhibits.

Transferable Skills You Build

- Research design: mixed methods; positionality statements; ethics protocols; data-return plans.

- Community collaboration: co-teaching, facilitation, memorandum-of-understanding drafting, conflict mediation.

- Archival & metadata work: provenance research, reparative description, Traditional Knowledge (TK) labels, rights & usage guidance.

- Counter-mapping & spatial analysis: participatory GIS, place-name recovery, sacred-site protections, impact storytelling through maps.

- Media & visual literacy: image provenance checks, de-stereotyping audits, inclusive casting/writing workflows.

- Data & tech auditing: dataset documentation, bias testing across dialect/skin-tone/locale, low-bandwidth and multilingual UX requirements.

Methods Toolkit

- Oral history & testimony: shared authority interviews, community custody of recordings, consent renewal.

- Archival repair: locating silences, reading against the grain, returning copies to families and local institutions.

- Textual & discourse analysis: close reading of law, policy, literature, and news for colonial grammars and euphemisms.

- Ethnography & participant observation: protocol-led fieldwork; reciprocity budgeting (transport, childcare, honoraria).

- Design justice practices: co-design workshops; harm-scenario planning; community review before publication.

Career Pathways & Roles

- Museums & heritage: provenance researcher, community-curation producer, repatriation coordinator, public historian.

- Education: curriculum designer, bilingual program lead, university/community partnership manager.

- Media & cultural industries: sensitivity editor, story consultant, diversity & equity lead, festival programmer.

- Policy & diplomacy: cultural-affairs officer, restitution negotiator, migration/border policy analyst.

- Development & NGOs: participatory-research specialist, land-rights advocate, climate justice program officer.

- Design & tech: inclusive UX researcher, dataset governance lead, localization strategist, ethics program manager.

- Analytics & insight: cultural data analyst mapping representation, pay equity, and supply-chain risk.

Sample Portfolio Projects

- Co-curated micro-exhibit with community captions and multilingual labels; evaluation via visitor feedback and partner review.

- Counter-map of extraction routes and resistance histories; open data with community-controlled access tiers.

- Bias audit of a media or AI dataset; remediation plan and documentation standard for future collections.

- Policy brief on restitution, land-back, or language revitalization with budget and implementation timeline.

- Audio storytelling or zine that returns research to participants, with consent for distribution and archiving.

How You Measure Impact

- Equity indicators: pay-gap closure, leadership representation, fair contracting with community partners.

- Cultural outcomes: number of returned objects and related care funding; language use in classrooms and public services.

- Access & UX: percent of content available offline/low-bandwidth; languages supported; screen-reader compliance.

- Research ethics: data-return completed; co-authorship or acknowledgment; harm-report resolutions and response time.

Who Should Study This (and Why)

- Students and educators: to build curricula that reflect plural histories and languages.

- Designers, data scientists, and engineers: to anticipate harms, design for diverse contexts, and document datasets responsibly.

- Policy makers and heritage professionals: to negotiate restitution, recognize customary law, and steward living cultures.

- Writers, curators, and journalists: to avoid extractive storytelling and cultivate accountable representation.

In short, studying postcolonial cultural studies trains you to connect history to systems, listen across languages, collaborate with care, and turn analysis into practice—skills that travel across sectors wherever justice, culture, and design meet.

Postcolonial Cultural Studies: Conclusion

Postcolonial cultural studies demonstrates that empire did not end so much as it hardened into the ordinary—into archives and school canons, visa queues and land titles, datasets and design defaults. It also shows how people refused those confinements by making new forms: creole languages, syncretic rituals, counter-archives, and solidarities that cross oceans. Reading these entanglements clarifies how yesterday’s conquest structures today’s markets, borders, and media—and how communities continue to author futures from within and beyond those structures.

The field’s promise lies in pairing critique with practice. Restitution becomes a workflow (provenance research, shared custody, community care funds); curriculum becomes multilingual and co-taught; archives return copies and custodial rights; design and data work adopt consent, documentation, and community governance; land-back recognizes custodianship and ecological knowledge. In short, scholarship turns into policy, partnerships, and prototypes that redistribute voice, value, and authority.

- Principles for the road ahead: consent and reciprocity; the right to opacity; shared authorship and benefit-sharing; accessibility across languages and bandwidths; accountability measured with communities, not only institutions.

- Measures of repair: languages used in classrooms and public services; objects and data returned with care funding; pay-gap closure and leadership diversity; models and interfaces tested across dialects, skins, and speeds; ecosystems co-managed with original custodians.

Studying postcolonial cultural studies therefore equips students and practitioners to read power with historical precision, to honor difference without voyeurism, and to co-create arrangements where knowledge is plural, culture is collaborative, and sovereignty—over land, language, story, and data—is shared and continually renewed.

Postcolonial Cultural Studies – Frequently Asked Questions

What is Postcolonial Cultural Studies?

Postcolonial Cultural Studies is an interdisciplinary field that examines how histories of colonialism and empire continue to shape cultures, identities, and power relations in the present. It explores how language, literature, film, media, and everyday practices carry traces of colonial domination and resistance, and how formerly colonised and marginalised groups negotiate voice, dignity, and representation in a world still marked by unequal power.

How does Postcolonial Cultural Studies relate to cultural history?

Postcolonial Cultural Studies is closely linked to cultural history because both are concerned with how people experience and interpret power through culture. Cultural history traces changing beliefs, symbols, and practices over time, while postcolonial perspectives foreground how colonial encounters, race, and empire shape those changes. Together, they help students see that culture is not neutral but formed in relation to conquest, resistance, and ongoing structural inequalities.

What are some key questions asked in Postcolonial Cultural Studies?

Key questions include: Who is allowed to speak and be heard in a given cultural context? How are colonised peoples, racialised communities, and Indigenous groups represented in literature, media, and public discourse? How do language and knowledge systems reflect colonial hierarchies? How do artists, writers, and activists challenge inherited narratives about civilisation, modernity, and progress?

Who are some influential thinkers in Postcolonial Cultural Studies?