Gender and cultural history sheds light on how identities, beliefs, and social norms evolve across time and space. To explore this rich field of inquiry, it is essential to understand its intersections with broader intellectual, political, and economic developments. For instance, examining the history of ideas provides insight into how philosophical movements and intellectual trends have shaped the understanding of gender roles and cultural values. Similarly, the history of political economy reveals how gendered labor divisions and social hierarchies were embedded in economic discourse and practice.

The political dimensions of culture become clearer when viewed alongside the history of political systems and their influence on societal norms. The rise of various social movements, explored in the history of social movements, often brought gender into public consciousness and policy debates. Meanwhile, the institutional legacy of statecraft can be traced through diplomatic history and diplomatic personalities, where cultural representation and gendered performances played notable roles.

Cultural perspectives on law and governance are further illuminated by themes such as post-colonial constitutionalism and revolutionary constitutions, both of which challenge dominant historical narratives. Cultural geography, although not listed here, would also offer complementary insights. Economic considerations tie closely to cultural interpretations in fields like economic history, financial history, and environmental economic history, each providing a different lens on how gendered experiences are shaped by material conditions.

Exploring cultural expression through popular culture and postcolonial cultural studies allows us to interrogate the mechanisms by which gender identities are represented and contested. Similarly, religious and spiritual history offers valuable insights into the ways spiritual belief systems have reinforced or challenged gender norms.

Historical analysis of conflict, as seen in economic history of warfare and guerrilla warfare and insurgency studies, reveals the complex role of gender in both the justification and experience of warfare. Beyond the battlefield, political engagement is explored through electoral history, electoral fraud and integrity, and electoral systems and political parties, where gender often influences participation and representation.

Broadly speaking, understanding history as a discipline entails grappling with the multifaceted roles that culture and gender have played across eras and regions. This is reinforced by links to the history of alliances and frameworks like economic thought and theory. Finally, the education history reminds us that gendered experiences of learning and pedagogy remain vital topics for historical reflection.

A vibrant, densely layered illustration visualizes the field of gender and cultural history. Classical busts, protest banners, courtroom scales, and gender symbols (♀ ♂) frame scenes of work, family, education, and activism across time. Gears, charts, and manuscripts suggest research and changing knowledge, while diverse figures—women, men, and non-binary people—move through courts, classrooms, factories, and marches. The composition highlights intersectional themes of power, law, labor, and representation, showing how gender identities are made, contested, and recorded in culture.

Table of Contents

Foundational Concepts & Methods

Key Concepts

- Sex vs. Gender: Sex refers to biological attributes (chromosomes, hormones, anatomy); gender refers to socially constructed identities, roles, and expectations.

- Gender Identity & Expression: A person’s internal sense of gender (e.g., woman, man, non-binary) and external presentation (clothing, speech, behavior).

- Sexuality: Patterns of attraction and practices; historically regulated by law, religion, and custom and represented through cultural texts.

- Intersectionality (Kimberlé Crenshaw): Social positions (gender, race, class, caste, disability, religion, nationality) combine to produce distinct experiences of power and inequality.

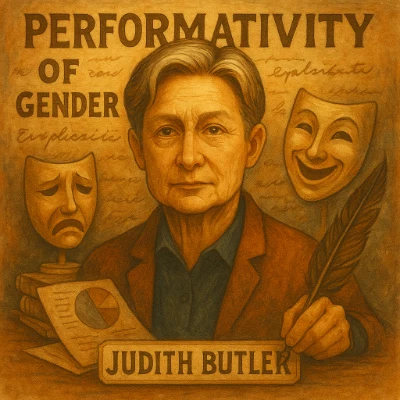

- Performativity (Judith Butler): Gender is not a fixed essence but performed through repeated acts, gestures, dress, and discourse that become “naturalized.”

- Hegemonic Masculinity (R. W. Connell): A dominant ideal of manhood that legitimizes men’s power over women and over marginalized masculinities.

- Separate Spheres & Domesticity: Ideology dividing public (productive, male) and private (reproductive, female) realms; continually contested across classes and cultures.

- Care Economy: Paid and unpaid labor that sustains life (child-care, elder-care, health work); often feminized and undervalued.

- Embodiment: How bodies are disciplined and signified (dress, beauty norms, medicalization, sport), and how they resist.

Primary Sources You Can Use

- Private writings: diaries, letters, memoirs, family recipe books—reveal everyday negotiations of gender.

- Official records: censuses, parish registers, court cases (especially family, morality, and labor disputes), poor-law files.

- Medical & legal texts: obstetrics manuals, sexology, criminal codes, witchcraft trials, “obscenity” legislation.

- Print & broadcast media: newspapers, magazines, advice columns, radio/TV scripts, advertising, fashion plates, comics.

- Visual & material culture: portraits, photography, clothing, uniforms, toys, household tools, cosmetics, sports equipment.

- Space & infrastructure: housing plans, workplace layouts, school timetables, public-toilet maps, transport rules (e.g., women-only carriages).

- Oral history & life narratives: interviews with elders, union activists, midwives, veterans, LGBTQ+ community members.

Methods & How to Apply Them

- Reading Against the Grain: Treat official sources as evidence of power; ask whose voices are missing and how coercion shaped the record.

- Discourse Analysis: Track how words and metaphors (e.g., “fallen woman,” “new man,” “respectability”) produce norms and exclusions.

- Visual/Material Analysis: Study posture, costume, color, and object wear to infer labor, class, and gendered meanings.

- Microhistory: Use a small case (a household, a trial) to illuminate wider structures of gender and culture.

- Quantitative & Demographic: Use censuses, wage books, and school rolls to chart shifts in marriage age, fertility, employment by sex.

- Spatial Approaches (GIS): Map gendered spaces—workplaces, markets, red-light districts, suffrage marches, safe houses.

- Comparative & Transnational: Follow ideas (suffrage, family planning, fashion) across borders; track colonial encounters and diaspora.

- Digital Humanities: Text-mine newspapers for gendered terms; build datasets of occupations by sex; create story maps of protests.

Ethics & Positionality

- Respect living communities: anonymize interviews when needed; obtain informed consent; avoid outing LGBTQ+ narrators.

- Contextualize historical language: Quote slurs or pathologizing terms sparingly and with critical framing.

- Reflexivity: State how your own identities and assumptions shape questions, access, and interpretation.

Mini Activity: Source Critique

- Select a one-page source (e.g., a 1920s cosmetics ad, a factory rulebook, or a court transcript).

- Identify: speaker, audience, purpose, and the gender norms invoked.

- List who is silenced or stereotyped; note intersections (class, race, religion, disability).

- Write a 150-word paragraph “reading against the grain” that shows what the source unintentionally reveals about power.

Key Takeaways

- Gender is historically constructed and performed; it varies across time, place, and social position.

- Combining cultural analysis with demographic, spatial, and material methods yields richer histories.

- Attention to ethics and reflexivity is essential when working with intimate or marginalized histories.

Global Turning Points & Chronology

Use this section as a scaffold for lectures or revision: each era lists what changed, why it mattered, sample sources, and quick class activities.

1) Ancient–Classical Worlds

- Shifts: Codified patriarchy in law and myth (e.g., Athenian citizenship, Roman patria potestas); parallel spaces of female religious authority (Vestal Virgins; priestesses of Isis).

- Why it mattered: Laid durable models of public/private division, honor/shame cultures, inheritance and dowry practices.

- Primary sources: Hesiod Works and Days, Athenian court speeches, Roman law (Digest), terracotta figurines, weaving tools, epitaphs.

- Activity: Compare an Athenian marriage contract with a Roman one; map rights and constraints for wives, daughters, enslaved women.

2) Medieval Religious Orders & Household Economies

- Shifts: Monasticism opens celibate routes to learning/power for some women; guilds structure gendered craft labor; Islamic courts record women’s property claims.

- Why it mattered: Shows non-linear opportunities—piety, property, and workshop membership could expand or restrict agency depending on locale.

- Primary sources: Convent rules, hagiographies, fatwas and court registers, guild ordinances, dowry chests, miracle images.

- Activity: “Household budget” role play: allocate labor across seasons for a peasant or artisan family; note gendered tasks and bargaining.

3) Early Modern Witchcraft, Honor & Empire

- Shifts: Witch persecutions police women’s bodies and healers; honor killings/duels regulate masculinities; European/Asian empires export domestic ideologies and interracial laws.

- Why it mattered: Links state formation and colonial rule to gender surveillance and racialized reproduction.

- Primary sources: Witch-trial transcripts, conduct books, East India Company records, missionary letters, sumptuary laws, portraits with gendered symbols.

- Activity: Examine a witch-trial testimony “against the grain”: which economic or neighborhood conflicts surface under moral language?

4) 19th-Century Industrialization & Reform

- Shifts: Factory work feminizes textiles; “separate spheres” ideology spreads; abolition, suffrage, and temperance movements use gendered moral claims.

- Why it mattered: Produces modern feminisms and labor politics; crystallizes wage/housework split and the idea of “respectability.”

- Primary sources: Factory rules, blue books, abolitionist newspapers, suffrage posters, domestic-servant ads, medical books on “hysteria.”

- Activity: Chart a mill worker’s 14-hour day vs. a middle-class housewife’s hidden labor; discuss whose work counts as “productive.”

5) 1914–1945: Total War & Biopolitics

- Shifts: Mass mobilization blurs gendered labor; states regulate reproduction (pronatalism, eugenics); sexual minorities policed/persecuted.

- Why it mattered: War opens jobs and suffrage in some nations yet reasserts domesticity after; reveals the politics of bodies at scale.

- Primary sources: Propaganda posters, ration books, Land Army records, internment/holocaust archives (incl. §175), nurses’ diaries, fashion coupons.

- Activity: Poster analysis: how do images of the “new woman”/“ideal soldier” script behavior? Rewrite one poster to subvert its message.

6) 1945–1980s: Decolonization, Second Wave, Cold War

- Shifts: New nations debate family law; contraception and divorce reform; civil-rights coalitions; queer organizing after Stonewall.

- Why it mattered: Expands rights beyond ballots to employment, education, bodily autonomy; raises intersectional critiques.

- Primary sources: UN conventions (CEDAW drafts), court cases, consciousness-raising pamphlets, early Pride flyers, TV ads for appliances.

- Activity: Mock legislative hearing on equal pay or family-law reform using period testimonies; track winners/losers by class and race.

7) 1990s–Present: Globalization, Digital Cultures & Backlash

- Shifts: Transnational care chains, NGO-ization of gender policy, #MeToo and online activism, legal recognition of same-sex marriage in many states, anti-gender movements.

- Why it mattered: Shows policy gains alongside new vulnerabilities (platform harassment, gig precarity, surveillance of bodies).

- Primary sources: NGO reports, social-media archives, court judgments, influencer content, esports/sport guidelines, corporate diversity policies.

- Activity: Build a mini–timeline for your country since 1990: three advances, three setbacks; annotate each with a primary source link.

Quick Revision Grid

| Era | Core Theme | One Source Type | Exam Angle |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical | Civic exclusion / sacred authority | Law codes, temple roles | How religion cut across patriarchy |

| Early Modern | Policing bodies & empire | Trials, colonial ordinances | Power through morality & race |

| Industrial | Work/domestic split | Factory rules, ads | Who counts as a “worker”? |

| 20th c. Wars | Biopolitics & mobilization | Propaganda, rationing | Temporary emancipation? |

| Since 1990 | Digital activism & backlash | Hashtags, court cases | Intersectional outcomes |

Gender, Body & Medicine

Ideas about sexed bodies have shifted with medical knowledge, religious belief, and state power. Cultural history tracks how anatomy, reproduction, disability, and appearance became sites of regulation and resistance.

From Humors to Hormones

- Premodern: Galenic “one-sex” models often framed women as cooler/weaker variants of men; menstruation and pregnancy explained via humors.

- 19th c.: New obstetrics/gynecology professionalizes control over childbirth; “hysteria” pathologizes women’s emotions.

- 20th c.: Endocrinology, contraception, IVF, and gender-affirming care transform possibilities and politics of embodiment.

Beauty, Dress & Respectability

- Dress codes, cosmetics bans, and hair regulations police class, religion, and gender (e.g., school rules; workplace grooming).

- Counter-styles—bobbed hair, miniskirts, queer fashion, natural-hair movements—recode bodies as political statements.

Disability & Care

- Gendered caregiving shapes who receives/does care; “invalid” stereotypes feminize vulnerability and marginalize disabled masculinities.

- Material culture—wheelchairs, prostheses, period products—reveals technology’s role in everyday dignity and access.

Primary Sources & Activities

- Sources: midwifery manuals, hospital casebooks, beauty ads, school dress codes, pharmaceutical leaflets, clinic consent forms.

- Activity: annotate a 1950s beauty advertisement: identify the “problem,” the ideal body, and who is excluded; rewrite the copy from an inclusive perspective.

Law, Family & Property

Marriage, inheritance, and kinship rules define rights to children, land, and work. They are crucial to understanding gendered power.

Marriage Systems

- Coverture & dowry: wives’ legal identity subsumed under husbands in many European codes; dowry/stridhan regulated assets in South Asia.

- Plural models: polygyny, woman–woman marriages (e.g., in parts of East Africa), matrilineal inheritance (e.g., Minangkabau, Mosuo).

Family Law Reforms (19th–21st c.)

- Married women’s property acts; divorce and custody reform; marital-rape criminalization; equal inheritance; recognition of same-sex marriage and adoption.

- Continuing debates: child marriage, guardianship, surrogacy, and reproductive rights.

Primary Sources & Activities

- Sources: marriage contracts, court petitions, guardianship files, inheritance suits, NGO legal guides.

- Activity: mock mediation: divide property and custody under two different legal regimes; reflect on winners/losers by class and gender.

Religion, Ritual & Sacred Spaces

Religions provide ethics and community but also script gendered obligations. Cultural history studies worship, pilgrimage, and authority alongside everyday ritual.

Authority & Leadership

- Debates over women clergy, female monastic orders, and lay leadership show shifting boundaries of sacred authority.

- Spirit possession, shrine caretaking, and healing circles often open space for gender-nonconforming roles.

Ritual & Space

- Segregated seating, veiling/unveiling, purity laws, and festival labor reveal how bodies are ordered in sacred places.

- Pilgrimage economies (vendors, lodging, media) redistribute gendered work and visibility.

Sources & Practice

- Sources: temple/church/mosque rules, festival posters, devotional songs, photographs of processions.

- Activity: map a ritual route: label who carries what, who sings, who watches, who profits; discuss inclusion/exclusion.

Work, Care & Welfare States

Care is the infrastructure of life. Economies and welfare systems rely on gendered expectations about unpaid and low-paid labor.

Care Chains & Migration

- Global domestic and nursing labor flows link households across borders; remittances support kin yet create “care deficits” at home.

- Legal statuses (au-pair, temporary worker, irregular migrant) shape vulnerability to exploitation.

Measuring Invisible Labor

- Time-use surveys expose unpaid hours; policy tools (parental leave, childcare subsidies, pensions for carers) redistribute care.

- COVID-19 revealed unequal burdens in home-schooling, elder care, and essential services.

Sources & Class Exercise

- Sources: domestic-worker contracts, recruitment ads, union leaflets, household budgets, time-use datasets.

- Activity: build a 24-hour “care clock” for two households (dual-income vs. single-parent); propose one policy that shifts the balance.

Colonialism, Empire & Gender

Empire exported domestic ideals, racial hierarchies, and sexual regulations while also creating hybrid cultures and resistance.

Rule of Difference

- Mixed-marriage bans, anti-miscegenation, and “protection of native women” policies policed intimacy to sustain racial order.

- Missionary schooling reshaped dress, domesticity, and masculinity; indigenous strategies adapted or resisted these scripts.

Labor & War

- Sex-segregated plantations, comfort systems, military brothels, and women’s wartime auxiliary units reveal coerced and voluntary roles.

- Decolonization movements mobilized mothers, market women, nurses, and students as political actors.

Sources & Task

- Sources: missionary journals, school readers, uniform regulations, anti-vice laws, veterans’ testimonies.

- Activity: compare two school primers (colonial vs. local press) for gendered lessons; present three visual cues that signal power.

Masculinities: Change & Diversity

Masculinity is plural and historical—warrior, bureaucrat, breadwinner, nerd, carer—each tied to class, race, and nation.

- Hegemonic ideals: soldier-citizen, rational administrator, athletic hero; often whitened/elite.

- Subordinate/complicit masculinities: enslaved men, colonized clerks, migrant laborers; queer and trans masculinities under surveillance.

- Contemporary shifts: stay-at-home fathers, care professions, mental-health advocacy, esports and creator economies.

Source set: draft cards, gym posters, men’s magazines, anti-violence campaigns, dad blogs. Mini task: storyboard a public-health poster that reframes help-seeking as strength.

Queer & Trans Histories

Beyond criminalization and pathologization are rich worlds of community, creativity, and everyday life.

- Pre-20th c.: molly houses, sworn sisterhoods, cross-dressing festivals, hijra/Two-Spirit roles.

- 20th c. urban subcultures: bars, ballrooms, magazines, clandestine networks; policing and resistance.

- Trans & gender-diverse life: medical gatekeeping, self-organized care, legal recognition, sports and ID debates.

- Culture: film, drag, literature, and digital platforms as archives of identity and kinship.

Sources: court records, bar guides, zines, oral histories, clinic files, Pride ephemera. Activity: curate a 6-item exhibit telling one local LGBTQ+ story across time.

Media, Popular Culture & Sport

Entertainment industries both reproduce and contest gender norms—through casting, sponsorship, and rules about bodies.

- Advertising & influencer culture: aspirational femininities/masculinities; wellness, “clean girl,” and “sigma male” narratives.

- Sport: amateurism barred women; Title IX-style reforms expanded participation; ongoing debates on pay equity and eligibility rules.

- Gaming & streaming: harassment and community moderation; new careers for women and queer creators.

Activity: code a 20-post social feed for gendered tropes (body talk, care work, aggression); present findings with 3 screenshots and one design recommendation for platforms.

Method Toolkit: Analysing Images & Ads

- Describe (who/what/where; composition, color, gaze, props, clothing).

- Contextualize (date, medium, audience, publisher/brand, circulation).

- Decode gender cues (posture, labor vs. leisure, speech bubbles, taglines).

- Power & Intersection (race/class/age/disability markers; who is missing?).

- Afterlives (memes, parodies, policy impacts).

Quick task: In 120 words, explain how one image naturalizes a gender role; attach a cropped detail that proves your claim.

Key Scholars & Short Glossary

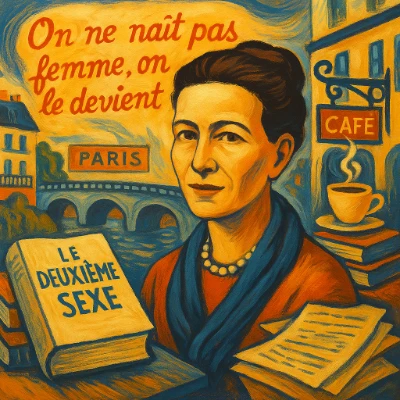

- Simone de Beauvoir: gender as becoming, not destiny.

A warm, painterly portrait places de Beauvoir amid Parisian symbols—bridge, café cup, notebooks, and the cover of Le Deuxième Sexe. The famous line in French arcs behind her, evoking existentialism and gender as a becoming rather than destiny.

- Angela Davis: race–class–gender in labor and prisons.

Rendered in bold oranges and blues, the image frames Davis as scholar-activist. A microphone and books signal teaching and organizing; stylized bars blossoming into flowers reference prison abolition and hope.

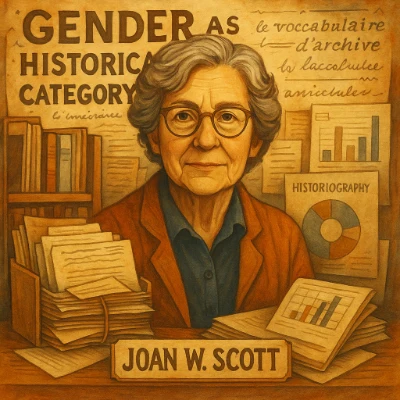

- Joan Scott: gender as a useful category of historical analysis.

Sepia papers, archival folders, and historiography charts encircle Scott, visualizing how her work reframed archives and narrative—reading sources “against the grain” to see power at work.

- Judith Butler: performativity of gender.

Earthy tones and stage symbols (comedy/tragedy masks, scripts) suggest performance. Butler’s calm gaze anchors the idea that gender norms endure through reiterated acts—and can be subverted.

- Raewyn Connell: hegemonic masculinity.

- Kimberlé Crenshaw: intersectionality.

The warm haloed background and crisp lettering present Crenshaw with courtroom calm. “Intersectionality” anchors the image, pointing to overlapping structures that shape lived experience and law.

Glossary

- Performativity: identities sustained through repeated acts.

- Respectability politics: conforming to dominant norms to claim rights.

- Care economy: paid/unpaid work that sustains people and communities.

- Biopolitics: state management of life (fertility, health, mortality).

- Studentification: urban change driven by rising student populations.

Assessment & Essay Prompts

- Comparative essay: “How did two different legal systems shape marriage and property for women, 1850–1950?” Use at least 6 primary sources.

- Source portfolio: 5 items (ad, legal text, photo, oral history, map) on a single theme (e.g., domestic service). 1,000-word commentary linking them.

- Digital project: build a story map of a local gender-history walk (10 sites, 200 words each, with images and citations).

- Policy brief (800 words): recommend one change to reduce the care gap in your country; include two historical precedents.

Further Reading

- Gender and the Politics of History — Joan W. Scott (theoretical foundations).

- The Second Sex — Simone de Beauvoir (classic philosophy of becoming).

- Manliness and Civilization — Gail Bederman (US masculinity & race).

- Women, Race & Class — Angela Y. Davis (intersectional labor struggles).

- Global Woman — Ehrenreich & Hochschild (transnational care chains).

- Digital: Women’s History primary-source portals; LGBTQ+ archives; labor union collections.

Gender and Cultural History: Review Questions and Answers:

1. What is gender and cultural history, and why is it significant?

Answer: Gender and cultural history is an interdisciplinary field that examines how gender roles and identities have been constructed and transformed within cultural contexts over time. It explores the interplay between societal norms, power structures, and individual experiences to understand how these dynamics influence both historical events and contemporary life. This area of study is significant because it challenges traditional historical narratives by highlighting marginalized voices and uncovering the often overlooked contributions of women and gender minorities. Ultimately, it provides a more comprehensive understanding of how culture and gender shape social identity and power relations.

2. How does cultural history contribute to our understanding of gender roles?

Answer: Cultural history contributes to our understanding of gender roles by analyzing the ways in which societal norms, traditions, and institutions have historically defined and regulated behaviors and expectations based on gender. It examines artistic expressions, literature, and everyday practices to reveal how gender roles have evolved and how they continue to influence individual and collective identities. By situating gender within broader cultural contexts, cultural history offers insights into the fluidity and variability of gender norms across different societies and epochs. This critical perspective helps to challenge stereotypes and encourages a more inclusive view of gender diversity.

3. What methodologies are used in researching gender and cultural history?

Answer: Researchers in gender and cultural history utilize a range of methodologies, including archival research, discourse analysis, ethnography, and visual analysis of cultural artifacts. These methods enable scholars to interpret texts, images, and other cultural products, uncovering the underlying ideologies and power dynamics that shape gender identities. By combining qualitative and quantitative approaches, researchers can trace historical trends and analyze how gender roles have been constructed, contested, and redefined over time. This multidisciplinary toolkit is essential for generating nuanced insights into the complex relationships between gender and culture.

4. How do feminist theories influence the study of cultural history?

Answer: Feminist theories influence the study of cultural history by providing analytical frameworks that critique patriarchal power structures and emphasize the role of women and marginalized genders in shaping historical narratives. These theories encourage scholars to re-examine historical sources with a focus on gender bias, uncovering the contributions and experiences that have traditionally been excluded from mainstream accounts. Feminist perspectives highlight the intersectionality of gender with race, class, and other social factors, enriching our understanding of cultural dynamics. As a result, the incorporation of feminist theories has led to more inclusive and diverse interpretations of the past.

5. In what ways can cultural history reveal the impact of gender on social and political power?

Answer: Cultural history reveals the impact of gender on social and political power by examining how gender norms and roles have been utilized to maintain or challenge existing power structures. It investigates the ways in which cultural practices, legal systems, and public institutions have historically reinforced gender hierarchies, while also documenting instances of resistance and change. Through the analysis of historical events, literature, and visual culture, scholars can illustrate how gender has been a critical factor in shaping leadership, authority, and social organization. This understanding helps to explain contemporary gender inequalities and informs efforts to create more equitable societies.

6. How does the intersection of gender and cultural identity shape historical narratives?

Answer: The intersection of gender and cultural identity shapes historical narratives by influencing the ways in which stories are told and remembered. Cultural history examines how gendered experiences interact with cultural practices, traditions, and social norms to create complex and often contested identities. This intersectionality reveals how different groups negotiate their roles within society and how these roles are embedded in historical contexts. By analyzing these interactions, scholars can challenge dominant narratives and highlight the diverse experiences that contribute to our understanding of the past.

7. What challenges do historians face when studying gender in cultural history?

Answer: Historians face several challenges when studying gender in cultural history, including the scarcity of primary sources that accurately represent the experiences of marginalized groups. Traditional historical records often reflect dominant perspectives, which can obscure or distort the contributions of women and gender minorities. Additionally, interpreting the symbolic language of gender in historical contexts requires careful analysis to avoid projecting contemporary ideas onto the past. Despite these challenges, innovative methodologies and interdisciplinary approaches enable historians to reconstruct a more accurate and inclusive picture of gender dynamics throughout history.

8. How can the study of gender and cultural history inform modern debates on equality and social justice?

Answer: The study of gender and cultural history informs modern debates on equality and social justice by providing a historical context for understanding the roots of gender inequality. By tracing the evolution of gender roles and examining the cultural factors that have perpetuated discrimination, scholars can identify the long-standing structures that continue to influence contemporary society. This historical perspective offers valuable insights into the mechanisms of social change and the potential for transforming oppressive systems. Ultimately, it serves as a powerful tool for advocating policies and practices that promote equality and social justice today.

9. How do artistic and literary works contribute to our understanding of gender in cultural history?

Answer: Artistic and literary works contribute to our understanding of gender in cultural history by reflecting the values, conflicts, and aspirations of different societies. Through the analysis of visual art, poetry, novels, and drama, cultural historians can uncover how gender is represented, contested, and reimagined over time. These creative expressions often serve as both mirrors and critiques of societal norms, offering insights into the lived experiences of individuals and communities. By studying these works, scholars gain a deeper appreciation for the role of art and literature in shaping and challenging gender identities and power structures.

10. What future directions might research in gender and cultural history take in the digital age?

Answer: Future directions in gender and cultural history research in the digital age may include the integration of digital humanities tools, such as data mining and digital archiving, to analyze vast quantities of cultural data. These tools can help uncover patterns and trends in gender representation across different media and historical periods. Additionally, interdisciplinary collaborations involving technology, sociology, and gender studies are likely to drive innovative research methodologies that offer new insights into the evolution of gender roles. This digital transformation will enable scholars to create more interactive and accessible platforms for exploring gender and cultural history, ultimately enriching our understanding of the past and its relevance to contemporary social issues.

Gender and Cultural History: Thought-Provoking Questions and Answers:

1. How might digital storytelling reshape the way gender and cultural history is documented and shared?

Answer:

Digital storytelling has the potential to transform the documentation and sharing of gender and cultural history by enabling the creation of multimedia narratives that combine text, audio, and visual elements. This innovative approach allows for the preservation of diverse personal experiences and cultural expressions in a format that is accessible to a global audience. By integrating digital tools such as video interviews, interactive timelines, and social media, historians can present complex gender narratives in engaging and relatable ways that traditional formats might not capture. This method not only democratizes access to historical knowledge but also provides a dynamic platform for marginalized voices to be heard.

Moreover, digital storytelling fosters collaboration between historians, technologists, and community members, leading to a richer, more nuanced understanding of cultural history. These collaborative projects can reveal the interplay between gender, identity, and cultural transformation by presenting a mosaic of lived experiences. As digital storytelling continues to evolve, it will likely redefine the boundaries of historical research and public engagement, making the study of gender and culture more interactive, inclusive, and impactful.

2. In what ways can the integration of virtual reality (VR) enhance the study of gender and cultural history?

Answer:

Virtual reality (VR) can enhance the study of gender and cultural history by providing immersive experiences that allow users to explore historical environments and cultural settings in three dimensions. Through VR, scholars and students can virtually visit historical sites, witness recreated cultural rituals, and interact with artifacts in a simulated environment, offering a tangible connection to the past. This immersive technology enables a deeper understanding of the spatial and cultural contexts that have shaped gender roles and identities over time. By experiencing historical narratives firsthand, users gain a more visceral sense of the challenges and transformations that have influenced gender dynamics throughout history.

Additionally, VR facilitates interdisciplinary collaboration by combining historical research with advanced digital technologies, resulting in innovative teaching tools and research methodologies. It allows for the visualization of complex data and the mapping of cultural shifts across time and space, providing insights that traditional methods may overlook. As VR becomes more widely adopted in academic settings, it will open up new avenues for engaging with cultural history, making the subject more accessible and relevant to contemporary audiences.

3. How might emerging social media trends influence public perceptions of gender and cultural history?

Answer:

Emerging social media trends are poised to significantly influence public perceptions of gender and cultural history by shaping how historical narratives are disseminated and discussed in digital spaces. Platforms such as Instagram, Twitter, and TikTok allow for the rapid sharing of visual and textual content that can challenge traditional narratives and introduce alternative perspectives on gender roles. Social media can democratize historical discourse by providing a space for marginalized voices and fostering a more interactive dialogue between scholars and the public. This dynamic exchange of ideas helps to reframe historical events in ways that resonate with contemporary audiences, making the study of gender and cultural history more relevant and accessible.

However, the influence of social media also presents challenges, such as the risk of oversimplification and the spread of misinformation. The rapid pace of content creation may lead to fragmented or superficial interpretations of complex historical issues. To address these challenges, historians and educators must engage actively with digital platforms, providing context and critical analysis to ensure that nuanced perspectives are communicated effectively. By leveraging the power of social media, cultural historians can foster a more informed public discourse that promotes deeper understanding and appreciation of gender dynamics and cultural heritage.

4. What are the potential effects of globalization on gender narratives within cultural history?

Answer:

Globalization has the potential to both challenge and reinforce gender narratives within cultural history by creating a complex interplay between local traditions and global influences. As cultures interact and blend, traditional gender roles may be reinterpreted or contested, leading to the emergence of hybrid identities that reflect a mix of local and global values. On one hand, globalization can introduce progressive ideas and feminist perspectives that challenge patriarchal structures, thereby empowering marginalized genders. On the other hand, the dominance of global media and economic forces may also reinforce existing stereotypes and contribute to the homogenization of gender roles across different societies.

This dual impact of globalization necessitates a critical examination of how gender narratives evolve in an interconnected world. Cultural historians can study the ways in which globalization influences public discourse, artistic expression, and social policies related to gender. By analyzing these trends, scholars can reveal the tensions between traditional cultural practices and modern influences, offering insights into how gender identities are continuously negotiated in the global arena. Ultimately, understanding these dynamics is crucial for promoting cultural diversity and gender equality in a rapidly changing world.

5. How might interdisciplinary collaboration between gender studies and cultural history deepen our understanding of societal change?

Answer:

Interdisciplinary collaboration between gender studies and cultural history can deepen our understanding of societal change by merging theoretical insights and research methodologies from both fields. Gender studies provides critical frameworks that analyze power, identity, and representation, while cultural history offers contextual analysis of how these elements have evolved over time. Together, they enable a comprehensive examination of how gender roles and cultural practices interact to shape social transformation. This collaborative approach can uncover hidden narratives and reveal the long-term impacts of gender dynamics on historical and contemporary societies.

Such interdisciplinary research not only enriches academic discourse but also informs practical approaches to addressing gender inequality and promoting social justice. By integrating diverse perspectives, scholars can develop innovative strategies for cultural preservation, policy-making, and community engagement that reflect the complexities of gender and culture. Ultimately, this collaboration leads to a more nuanced understanding of societal change, highlighting the interconnectedness of historical legacies and modern social challenges.

6. How can cultural historians use personal narratives to illuminate the experiences of gender minorities throughout history?

Answer:

Cultural historians can use personal narratives to illuminate the experiences of gender minorities by collecting and analyzing oral histories, diaries, letters, and autobiographical accounts that document the lived experiences of individuals from marginalized groups. These personal narratives offer rich, intimate insights into the challenges, resistances, and triumphs of gender minorities, providing a counterpoint to dominant historical records that often overlook these perspectives. By incorporating these stories into broader historical analyses, cultural historians can construct more inclusive narratives that capture the diversity and complexity of human experience. This approach not only humanizes historical events but also validates the contributions of gender minorities, enriching our overall understanding of cultural history.

Furthermore, the use of personal narratives allows historians to explore the emotional and psychological dimensions of gender identity, revealing how societal pressures and cultural expectations have shaped individual lives. These narratives also serve as a powerful tool for advocating social justice and raising awareness about the historical marginalization of gender minorities. By highlighting these voices, cultural historians contribute to a more equitable and comprehensive interpretation of the past.

7. How might art and literature be used as tools to challenge traditional gender norms in historical narratives?

Answer:

Art and literature can be used as powerful tools to challenge traditional gender norms in historical narratives by offering alternative representations and counter-narratives that subvert conventional expectations. Through creative expression, artists and writers often question societal norms, portray diverse gender identities, and highlight the experiences of those who have been marginalized. These cultural products provide a medium for critical commentary on the roles and expectations imposed by dominant gender ideologies, inviting audiences to reconsider and reinterpret historical events and cultural practices. By analyzing such works, cultural historians can uncover the ways in which art and literature serve as forms of resistance and catalysts for social change.

Moreover, the integration of art and literature in historical analysis allows for a more nuanced understanding of the interplay between aesthetics, identity, and power. These creative works often capture the emotional and subjective dimensions of gender experiences, offering insights that traditional historical documents may overlook. As a result, art and literature not only enrich our understanding of gender in the past but also inspire contemporary discussions about equality, representation, and social transformation.

8. How can public memory and commemoration practices shape our understanding of gender in history?

Answer:

Public memory and commemoration practices play a significant role in shaping our understanding of gender in history by influencing which events, figures, and narratives are remembered and celebrated. Monuments, memorials, and public holidays often reflect dominant cultural values, and the inclusion or exclusion of certain gendered perspectives can either reinforce or challenge traditional historical narratives. By critically examining these commemorative practices, cultural historians can reveal the underlying power dynamics and ideological choices that shape collective memory. This analysis helps to understand how public memory is constructed and the extent to which it represents diverse experiences, particularly those of marginalized genders.

In addition, the evolution of commemoration practices over time can illustrate shifting attitudes toward gender and social justice. As societies become more inclusive, public memory may increasingly recognize the contributions of women and gender minorities, leading to a more balanced historical narrative. Understanding these processes is crucial for developing policies and educational programs that promote an accurate and inclusive representation of the past, ultimately contributing to a more equitable cultural legacy.

9. How might changing social attitudes toward gender influence the future of cultural historical research?

Answer:

Changing social attitudes toward gender are likely to influence the future of cultural historical research by encouraging more inclusive and critical examinations of historical narratives. As contemporary society places greater emphasis on gender equality and the recognition of diverse identities, cultural historians are increasingly re-evaluating traditional accounts that may have marginalized or distorted gendered experiences. This shift in perspective leads to the incorporation of feminist, queer, and intersectional theories into historical analysis, which enrich the field by highlighting previously overlooked contributions and challenging established power structures. Consequently, future research will likely produce more nuanced and representative accounts of the past that reflect the complexities of gender and social identity.

Moreover, evolving social attitudes can stimulate interdisciplinary collaborations that bring together scholars from various fields to explore the intersections of gender, culture, and history. These collaborations can foster innovative methodologies and broaden the scope of research, ensuring that cultural history remains relevant in addressing contemporary issues. The dynamic interplay between current social trends and historical inquiry promises to drive significant advancements in the way we understand and interpret gender in historical contexts.

10. What challenges do scholars face when incorporating gender perspectives into traditional historical narratives?

Answer:

Scholars face several challenges when incorporating gender perspectives into traditional historical narratives, including the scarcity of primary sources that represent the experiences of women and other gender minorities. Traditional archives often reflect the dominant power structures of their time, which can result in biased or incomplete accounts of history. Additionally, researchers must navigate the complexities of interpreting gendered language and cultural symbols that may have different meanings in various historical contexts. These challenges require a careful and critical approach to source analysis, as well as the development of new methodologies that can uncover hidden narratives and give voice to marginalized groups.

Furthermore, incorporating gender perspectives often involves reinterpreting established historical accounts, which can be met with resistance from traditional scholars or institutions. Balancing the need for academic rigor with the imperative to challenge long-held assumptions is a delicate task that demands both theoretical innovation and methodological flexibility. Despite these obstacles, the integration of gender perspectives is essential for creating a more comprehensive and just historical record that accurately reflects the diverse experiences of the past.

11. How can cultural geography and history intersect to provide insights into gendered spatial practices?

Answer:

Cultural geography and history intersect to provide insights into gendered spatial practices by analyzing how different spaces—such as homes, workplaces, and public arenas—are organized and experienced differently by various genders. This interdisciplinary approach examines how gender roles influence the design, use, and perception of space, revealing the underlying social dynamics that shape everyday life. By studying spatial practices, scholars can uncover how cultural norms and historical events have contributed to the segregation or integration of genders within specific environments. This analysis not only enhances our understanding of gender inequality but also informs contemporary discussions about urban planning and social inclusion.

Moreover, the combination of historical context and spatial analysis enables researchers to trace the evolution of gendered spaces over time, highlighting shifts in societal values and power relations. For example, examining the transformation of public spaces can reveal how increased gender equality has influenced the design and use of urban environments. This interdisciplinary perspective enriches our understanding of the intimate connection between space, culture, and gender, offering valuable insights into both historical and contemporary social structures.

12. How might emerging digital tools reshape the methodologies used in gender and cultural history research?

Answer:

Emerging digital tools have the potential to reshape the methodologies used in gender and cultural history research by enabling more comprehensive and data-driven analyses of historical sources. Tools such as digital archives, text mining software, and interactive mapping platforms allow researchers to access and analyze vast amounts of data that were previously difficult to manage. These technologies facilitate the identification of patterns and trends in gender representation across different time periods and cultural contexts, providing a more nuanced understanding of historical dynamics. Digital methodologies also enhance collaboration among scholars by enabling the sharing and synthesis of large datasets, which can lead to more innovative and interdisciplinary research outcomes.

Furthermore, the integration of digital tools can democratize the research process, making it easier for a wider range of voices to contribute to historical narratives. This shift not only broadens the scope of research but also promotes transparency and accessibility in academic inquiry. As these tools continue to evolve, they will likely lead to the development of new theoretical frameworks and methodological approaches that better capture the complexities of gender and cultural history. Ultimately, the digital transformation of research methodologies promises to enrich our understanding of the past and inform more equitable interpretations of history.

Last updated: