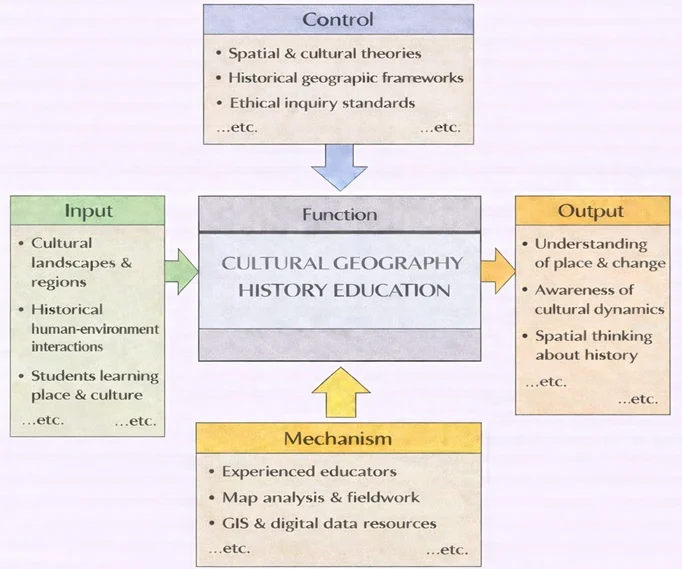

Cultural Geography History Education tells the story of the past through the lens of place. Instead of beginning with rulers and dates, it begins with landscapes, regions, routes, and boundaries—then asks how human choices and environments shaped one another over time. The inputs include cultural landscapes and regions that anchor learning in real locations, historical human–environment interactions that reveal patterns of settlement, trade, migration, and land use, and students who want to understand how culture becomes visible in space. The learning process is guided by controls such as spatial and cultural theories, historical geographic frameworks, and ethical inquiry standards, helping students interpret evidence carefully, avoid oversimplified stereotypes, and respect the communities represented in maps and records. The function is enabled by mechanisms like experienced educators, map analysis and fieldwork that train observation and inference, and GIS and digital data resources that allow students to compare layers of information across time. When these elements work together, the outputs are distinctive: a deeper understanding of place and change, sharper awareness of cultural dynamics, and stronger spatial thinking about history—seeing how the past leaves traces not only in texts, but also in the geography of everyday life.

Cultural geography explores the intricate ways in which human societies shape—and are shaped by—their geographic environments, through belief systems, cultural practices, and spatial organization. This discipline offers a rich interface with the history of ideas, particularly in understanding how philosophical concepts and intellectual movements influenced the development of regional identities and landscapes. Students engaging with cultural geography benefit from insights drawn from history of political economy, especially in examining how governance structures intersect with cultural and spatial dynamics.

The legacies of colonization and independence movements are particularly relevant to cultural geography, as seen in topics like post-colonial constitutionalism and postcolonial cultural studies. These fields examine how spatial claims and symbolic geographies are contested and redefined through historical processes. Understanding revolutionary constitutions also helps uncover how cultural narratives are embedded within national spaces and territorial boundaries.

Exploring religious and spiritual history enriches our grasp of sacred geographies and pilgrimage landscapes, while the evolution of education history reveals how learning institutions became central to national identity formation. Similarly, popular culture serves as a lens to examine the symbolic use of space in everyday life, whether through media representations or urban subcultures.

The discipline is also closely aligned with political and military geographies. Themes from guerrilla warfare and insurgency studies inform understandings of contested terrains, while the history of political systems and electoral systems and political parties explain spatial patterns of political mobilization. Geopolitical arrangements and international spatial hierarchies are also illuminated by the study of diplomatic history and the influence of diplomatic personalities.

Furthermore, economic forces shape cultural spaces significantly. Insights from economic history, financial history, and economic diplomacy show how trade networks and capital flows influence cultural landscapes. The environmental economic history perspective adds depth to how cultural groups adapt to or reshape ecological zones, while studies in economic thought and theory reveal ideological undercurrents behind spatial development.

At a broader level, cultural geography intersects with global political thought by analyzing the symbolic power of nations and the narratives that bind places to identities. This is complemented by examining electoral fraud and integrity and electoral history, which highlight how space and place influence—and are influenced by—public trust and representation. Finally, the study of history of alliances underscores how geographic and cultural affinities shape long-term strategic partnerships.

A vivid collage maps how culture shapes places and how places shape culture. A blue river threads markets, neighborhoods, and boats while iconic landmarks—Taj Mahal, Big Ben, Golden Gate-like bridge, minarets, ferris wheel—rise from overlapping maps and diagrams. People gather, trade, and travel; gears and compasses suggest the systems and routes that connect regions. The whole scene blends natural features with built environments to illustrate core themes of cultural geography: diffusion, interaction, identity, and the global networks that tie local places together.

Table of Contents

Cultural Geography — At a Glance

What it studies

How people, beliefs, and practices shape spaces—and how places shape people.

Key lenses

Urban landscapes · migration · regions & identities · nature–culture relations · symbols.

Why it matters

Explains patterns of belonging, conflict, heritage, tourism, and policy on a changing planet.

Skills you gain

Spatial thinking · map literacy · fieldwork ethics · data + story integration.

Key Focus Areas in Cultural Geography

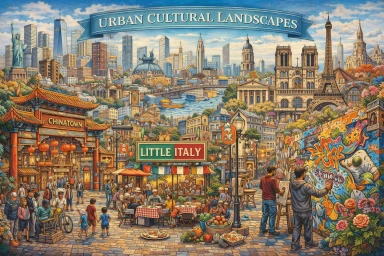

Urban Cultural Landscapes

Urban cultural landscapes are the physical and symbolic spaces within cities that reflect cultural identities and practices.

Defining Urban Cultural Landscapes

- The built environment of cities—such as architecture, public spaces, and infrastructure—represents the cultural values and history of its inhabitants.

- Examples:

- New York City’s diverse neighborhoods, such as Chinatown and Little Italy, highlight the cultural imprint of immigrant communities.

- Paris’s Haussmannian boulevards and iconic landmarks like the Eiffel Tower symbolize French cultural and historical identity.

Urbanization and Culture

- Urbanization influences cultural practices by fostering interaction between diverse groups.

- Examples:

- Cities as centers of artistic innovation, such as the Harlem Renaissance in 1920s New York.

- Street art and graffiti as cultural expressions in urban environments, seen in cities like Berlin and São Paulo.

Challenges in Urban Cultural Geography

- Urban renewal and gentrification often disrupt cultural landscapes, displacing long-established communities.

- Balancing heritage preservation with modernization in rapidly urbanizing cities.

Migration Patterns

Migration is a significant focus in cultural geography, highlighting how the movement of people shapes cultural diffusion and transformation.

Cultural Diffusion Through Migration

- Migration spreads ideas, languages, religions, and traditions, influencing the cultural fabric of destination regions.

- Examples:

- The spread of Buddhism from India to East Asia through ancient trade routes like the Silk Road.

- The global influence of diasporic communities, such as Indian cuisine becoming popular worldwide.

Types of Migration

- Voluntary Migration:

- Examples: Economic migration for better opportunities, such as South Asians moving to the Gulf states.

- Forced Migration:

- Examples: The transatlantic slave trade or the displacement of Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar.

- Rural-to-Urban Migration:

- Impact: Urbanization in countries like China, where millions have moved from rural areas to cities, reshaping cultural landscapes.

- Voluntary Migration:

Challenges and Impacts

- Cultural assimilation and the preservation of heritage in host societies.

- Tensions arising from cultural diversity, leading to policies like multiculturalism or assimilation.

Regional Traditions and Identities

Cultural geography examines how regions develop unique traditions and identities shaped by their physical and historical contexts.

Defining Regional Cultures

- Regional traditions are influenced by factors like climate, topography, and natural resources.

- Examples:

- Mediterranean cuisine reflects the region’s agricultural abundance of olives, wheat, and grapes.

- Indigenous practices in the Amazon, such as sustainable hunting and gathering, are adapted to the rainforest environment.

Cultural Regions

- Formal Cultural Regions:

- Defined by shared characteristics, such as language or religion.

- Example: Latin America, where Spanish and Portuguese are predominant languages, and Catholicism is widely practiced.

- Functional Cultural Regions:

- Defined by interactions and activities, such as metropolitan areas where people commute for work.

- Vernacular Cultural Regions:

- Defined by local perceptions, such as the “Deep South” in the United States.

- Formal Cultural Regions:

Preservation of Regional Traditions

- Cultural geography helps document and protect endangered traditions, such as indigenous languages or artisanal crafts.

The Interaction Between Environment and Culture

Cultural geography explores how physical environments influence cultural behaviors and how human activities modify landscapes.

Environmental Determinism

- The theory that physical environments directly shape human culture.

- Historical Example: The Nile River’s fertile floodplains influenced ancient Egyptian agricultural practices and religious beliefs.

Cultural Ecology

- Focuses on the reciprocal relationship between humans and their environment.

- Examples:

- The development of terrace farming in the Andes to adapt to steep slopes.

- Nomadic herding in arid regions like the Sahara, where resources are scarce.

Environmental Modification

- Humans actively shape their environments to suit cultural needs.

- Examples:

- The Netherlands’ extensive use of dikes and polders to reclaim land from the sea.

- Deforestation for agriculture in regions like the Amazon, with significant cultural and ecological consequences.

The Role of Cultural Symbols in Geography

Cultural geography investigates the symbolic meanings attached to places and landscapes.

Sacred Spaces

- Many cultures designate certain locations as sacred, reflecting religious or spiritual significance.

- Examples:

- The Ganges River in Hinduism as a symbol of purification.

- Jerusalem as a sacred city for Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

Monuments and Landmarks

- Monuments serve as cultural symbols, representing historical achievements or collective memory.

- Examples:

- The Taj Mahal in India as a symbol of love and Mughal architectural heritage.

- Mount Rushmore in the U.S., representing national pride and identity.

Cultural Festivals

- Festivals tied to specific locations highlight the interaction between culture and geography.

- Examples:

- Rio de Janeiro’s Carnival, celebrated as part of Brazil’s cultural identity.

- Japan’s cherry blossom festivals, emphasizing the cultural significance of nature.

This illustration brings together diverse cityscapes and cultural symbols to visualize key ideas in cultural geography. Neighborhoods such as Chinatown and Little Italy, iconic landmarks like the Eiffel Tower, and expressions like street art and public markets reveal how urban spaces become living records of identity, migration, creativity, and social interaction. The image highlights how cities are not just physical environments, but dynamic cultural landscapes shaped by history, movement of people, and everyday human expression.

Methods & Data for Cultural Geography

- Fieldwork & Ethnography: walking interviews, participant observation, sketch maps, photo-elicitation.

- Mapping & GIS: thematic maps of language, religion, festivals; story maps combining narrative + spatial data.

- Remote Sensing & Imagery: land-use change, urban expansion, cultural landscape detection.

- Text & Media Analysis: place branding, tourism brochures, film/TV locations, social media geotags.

- Archives & Oral History: historical maps, planning files, community memories, heritage inventories.

- Ethics & Inclusion: informed consent, representation of vulnerable groups, data sovereignty.

Tip: pair quantitative layers (e.g., census, mobility) with qualitative insights (stories, photos) for fuller explanations.

Key Terms & Concepts

- Cultural Landscape

- Visible imprint of human activity on the earth—buildings, field patterns, signage, sacred sites.

- Place

- Space made meaningful through lived experience, memory, and identity.

- Diffusion

- How practices, beliefs, or innovations spread across space (relocation, contagious, hierarchical).

- Sense of Place

- Emotional ties and narratives that connect people to locations.

- Hybridization

- Mixing of cultural forms through contact—often visible in food, music, language, and urban design.

- Scale

- Analytical level (neighborhood ↔ global) at which patterns are examined; patterns can shift by scale.

Applications of Cultural Geography

Urban and Regional Planning

- Cultural geography informs planners about preserving cultural heritage while accommodating growth.

- Example: Designing culturally inclusive urban spaces in multicultural cities like Toronto or Singapore.

Tourism Development

- Understanding cultural geography enhances sustainable tourism by respecting local traditions and minimizing cultural commodification.

- Example: Promoting ecotourism in indigenous communities while preserving their cultural heritage.

Policy and Multicultural Integration

- Cultural geography provides insights for managing cultural diversity and promoting social cohesion.

- Example: Policies in Canada that emphasize multiculturalism and the celebration of diverse cultural identities.

Climate Adaptation

- Analyzing how cultural behaviors respond to environmental changes aids in creating effective climate adaptation strategies.

- Example: Supporting indigenous knowledge systems for sustainable resource management in vulnerable ecosystems.

Regional Snapshot: Historic District Gentrification (Urban Europe)

A warm, flat-style illustration shows Lisbon’s Alfama: a yellow tram curves along the river beside tiled paving, while people sit at street cafés and a couple with luggage heads toward a doorway marked with an Airbnb sign. Stacked hillside houses and a white church dome rise behind arched bridge spans. The scene captures gentrification pressures—tourism growth, platform rentals, and a shift from everyday services to visitor-oriented businesses—set against the neighborhood’s historic charm.

Place & context

Alfama, Lisbon’s oldest hillside quarter overlooking the Tagus, has narrow lanes, fado houses, and long-time residents. Following a tourism boom and the rise of short-term rentals, the district experienced rapid amenity upgrades—and resident turnover.

What changed

- Housing market shift: apartments converted to short-term rentals; higher rents pushed out multi-generational households.

- Streetscape: more cafés, souvenir shops, and luggage storage; fewer everyday services (hardware, tailor, grocer).

- Temporal rhythms: daytime cruise-ship visitors and evening fado audiences replaced neighborhood routines.

- Regulation: heritage protections limit façade change, but not always tenancy change; caps and licensing were later introduced in parts of the city.

Spatial cues to observe

- Density of digital-platform signage vs. mailboxes/bell plates of long-term tenants.

- Street noise and crowding near scenic overlooks; tram lines as tourist corridors.

- Renovated façades clustered around view streets; under-investment on back alleys.

Data you can map

- Registered short-term rentals by building; rent levels over time; resident age structure.

- Business mix: everyday services vs. visitor-oriented retail and F&B.

- Noise/footfall sensors; complaint data; heritage-zone boundaries.

Discussion prompts

- Who benefits from value uplift—owners, platforms, the city tax base, or cultural workers?

- Which policies (rent caps, licensing quotas, community-land trusts) protect resident diversity while sustaining heritage and livelihoods?

Regional Snapshot: Overtourism & Resident Pushback (Barcelona)

Artist impression — Barcelona, El Born/Barri Gòtic: dense visitor flows and short-term rentals collide with everyday life in the medieval core.

Artist impression — Barcelona, El Born/Barri Gòtic: dense visitor flows and short-term rentals collide with everyday life in the medieval core.A warm, flat-style drawing shows Barcelona’s El Born/Gothic-quarter streets lined with balconies and souvenir displays. Visitors in sunhats and backpacks film the scene while a resident at the center raises a Catalan sign—“El Born és per veïns.” On the right, a keypad and labels hint at platform apartments; a scooter, no-parking sign, and cluttered doorway suggest congestion. The image captures the cultural-geography tension between everyday life and visitor economies: housing pressure, commercialization of public space, and community pushback in a protected historic core.

Place & context

Barcelona’s historic center (Ciutat Vella) concentrates world-class heritage, nightlife, and retail. Visitor numbers and platform rentals surged post-2000s, especially in El Born and the Gothic Quarter.What changed

- Housing pressure: apartments converted to tourist lets; rising rents and fewer long-term leases.

- Public space stress: crowding in alleys and plazas; noise at night; delivery congestion by day.

- Policy response: special urban plans (PEUAT), rental licensing caps, fines on illegal listings, resident-only access pilots in some streets.

Spatial cues to observe

- Doorbells with multiple coded units; luggage lockers; “apartments turístics” licensing stickers.

- Queue spillovers at selfie hotspots; scooter and e-bike delivery nodes.

- Plaza acoustic patterns—amplified busking vs. quiet side courts.

Data you can map

- Licensed vs. illegal short-term rentals; rental price trends; resident age structure.

- Footfall by hour; noise complaints; waste tonnage on festival weekends.

- Business mix shift: daily services → souvenir/F&B density by block.

Discussion prompts

- Which mixes of licensing, zoning, and enforcement actually reduce displacement?

- How can mobility (delivery windows, pedestrianization, micro-hubs) restore liveability without harming livelihoods?

Regional Snapshot: Creative-Led Regeneration (Bilbao)

Artist impression — Bilbao, Abandoibarra/Nervión: from steel and shipyards to culture-tech waterfront anchored by the Guggenheim.

Artist impression — Bilbao, Abandoibarra/Nervión: from steel and shipyards to culture-tech waterfront anchored by the Guggenheim.A flat, warm-toned scene shows the Nervión river curving past the gleaming Guggenheim Museum. People stroll, cycle, and sit on benches; new trees and public art punctuate the walkways. In the foreground, project staff in safety vests review plans beside a “Bilbao Regeneration” sign, signaling coordinated investments in culture, transit, and public space. The image highlights how deindustrial land became a civic waterfront, with creativity, environmental repair, and access driving urban change.

Place & context

Bilbao’s deindustrialization opened up large riverfront tracts. A culture-infrastructure strategy (Guggenheim, metro, bridges, parks) spurred reinvestment and rebranding.What changed

- Land use: industrial plots → museums, parks, housing, and creative offices.

- Public realm: continuous promenades; new bridges; river as civic spine.

- Economy: tourism and creative sectors grow; service jobs replace heavy industry.

Spatial cues to observe

- Adaptive reuse of warehouses; pop-up art and maker spaces in old sheds.

- Wayfinding linking museums, parks, and neighborhoods; flood-resilient design.

- Night-time economy nodes around cultural venues; seasonal event clustering.

Data you can map

- Before/after employment by sector; property values; new-build vs. reuse ratio.

- Visitor flows by route; festival calendars; transit ridership to riverfront stops.

- Environmental indicators: river water quality, tree canopy, heat-island change.

Discussion prompts

- Does creative-led growth diversify the economy or expose it to tourism shocks?

- How do benefits reach adjacent working-class districts (housing, training, public space)?

Regional Snapshot: Heritage & Studentification (Bologna)

Artist impression — Bologna, University Quarter under the porticoes: balancing UNESCO-listed heritage with rising student housing demand.

Artist impression — Bologna, University Quarter under the porticoes: balancing UNESCO-listed heritage with rising student housing demand.A warm, flat-style scene depicts Bologna’s historic core with the Two Towers and arcaded “Università” façade. Students walk with books and laptops; others eat at terrace tables beneath awnings marked “Pasta” and “Pizza.” The lively street life hints at studentification: growing student populations, cafés and night economy, and pressure on rental housing within a protected heritage setting. The image conveys the cultural-geography balance between learning, local business, and resident liveability.

Place & context

Bologna’s University Quarter hosts one of Europe’s oldest universities. Historic apartments and porticoed streets face high demand from students, Erasmus visitors, and platform rentals.What changed

- Housing market: room-by-room lets, rising rents, and shrinking family tenancy.

- Street life: vibrant cafés and night economy; noise and litter frictions with long-term residents.

- Management: noise-control ordinances; student housing projects; campaigns for responsible nightlife.

Spatial cues to observe

- “Affittasi” postings and WhatsApp QR codes on notice boards and pillars.

- Day vs. night rhythms under porticoes; café terraces vs. quiet academic cloisters.

- Presence of co-living blocks and renovated attics near faculties.

Data you can map

- Rent levels per room; formal vs. informal listings; student population by parish/sector.

- Noise complaints and cleaning frequency; opening hours; terrace permits.

- New student housing beds vs. demand; commuting patterns to campus.

Discussion prompts

- What housing models (co-ops, public–private halls, rent caps) keep the quarter mixed and affordable?

- How to protect UNESCO heritage and portico ambience while supporting student life and local business?

Regional Snapshot: Diaspora Marketplace (Southeast Asia)

Artist impression — Melaka, Jonker Street by the Malacca River: a diaspora marketplace where Peranakan, Chinese, Malay, and global influences mix.

Artist impression — Melaka, Jonker Street by the Malacca River: a diaspora marketplace where Peranakan, Chinese, Malay, and global influences mix.A bold, flat-style night scene of Jonker Walk in Melaka’s heritage quarter. Under a glowing sign in English and Chinese, crowds stroll between rows of historic shophouses while lanterns and street banners hang overhead. Vendors sell snacks and crafts from lit stalls; couples and families mingle in the warm evening light. The image highlights the diaspora marketplace character of Jonker Street—multilingual signage, hybrid foods, and tourism woven into a preserved riverfront streetscape.

Place & context

In Melaka’s UNESCO-listed core, Jonker Street (Jalan Hang Jebat) becomes a weekend night market. Historic shophouses host Peranakan bakeries, clan associations, and new artisanal stalls serving tourists and local families.What changed

- Hybrid commerce: traditional snacks and crafts sit beside fusion cafés and trendy dessert kiosks.

- Language ecology: Malay, English, and multiple Chinese scripts appear on signboards; QR-code menus bridge visitors and vendors.

- Riverside reuse: promenades and boat tours reorient the city toward the water; murals and lighting extend hours of use.

- Diaspora networks: goods, skills, and remittances link local traders to relatives overseas.

Spatial cues to observe

- Lantern corridors and festival arches; clan hall thresholds; five-foot ways as social spillover space.

- Multilingual shopfronts; menu code-switching; halal/vegetarian signage.

- Riverside seating, boat jetties, and mural clusters forming photo hotspots.

Data you can map

- Stall types by block; evening vs. daytime footfall; boat-tour embarkation points.

- Price bands and product origins; language distribution on signs.

- Resident–visitor mix by hour; festival calendars vs. congestion.

Discussion prompts

- How can heritage conservation support both resident needs and small-vendor resilience?

- What crowd-management and waste systems keep the river clean during peak nights?

Regional Snapshot: Sacred Waters & Tourism (South Asia)

Artist impression — Varanasi, ghats on the Ganges: ritual bathing and evening aarti share the riverfront with boat tours and smartphone photography.

Artist impression — Varanasi, ghats on the Ganges: ritual bathing and evening aarti share the riverfront with boat tours and smartphone photography.A warm, painterly view of the Varanasi riverfront shows terraced ghats descending to the Ganges under a golden sky. Temple towers rise above the steps while groups of devotees in orange robes gather beneath round parasols; others sit quietly by the water. A rowboat glides past, and a visitor lifts a phone to photograph the scene. The image evokes the living ritual landscape of the ghats—daily worship and bathing alongside tourism and river traffic—bathed in swirling sunset light.

Place & context

Varanasi’s stepped ghats are sacred bathing places and cremation sites. The riverfront is a living ritual landscape drawing residents, pilgrims, and global visitors.What changed

- Tourism overlay: sunrise/sunset boat circuits and viewing terraces expand alongside ritual pathways.

- Infrastructure: lighting, CCTV, and riverside promenades improve safety but can alter ritual ambiance.

- Environmental management: intensified efforts for waste collection, water testing, and festival-day crowd control.

Spatial cues to observe

- Processional routes from temples to ghats; zones for puja vs. photography; ticketed platforms.

- Boat queuing points and informal vendors; soundscapes of bells, chants, and generators.

- Signage for cleanliness campaigns; segregated waste points; police and volunteer posts.

Data you can map

- Boat traffic density by hour; ritual calendars; festival crowd estimates.

- Water-quality sampling points; waste-collection routes; bathing vs. cremation ghat functions.

- Visitor origin surveys; accommodation clusters; heritage-buffer zones.

Discussion prompts

- How can sacred viewsheds and ritual privacy be protected while enabling livelihoods from tourism?

- Which stewardship models (community trusts, pilgrim guides, riverfront maintenance funds) work best?

Why Study Cultural Geography

Understanding the Relationship Between People and Place

Exploring Identity, Belonging, and Symbolic Meaning

Connecting Geography to Contemporary Global Issues

Developing Spatial Thinking and Research Skills

Preparing for Interdisciplinary and Impactful Careers

Try It Yourself: Analyze a Place

- Choose a site: a market street, temple precinct, train station square, or riverside park.

- Observe: sketch a quick map; note languages on signs, smells/sounds, flows of people, times of peak use.

- Photograph ethically: avoid faces without consent; focus on material cues (architecture, stalls, rituals).

- Interview: 3 brief conversations—ask how people use the place and what it means to them.

- Synthesize: 5–7 insights connecting landscape features to identity, power, and change.

Deliverable: one annotated map + 200-word interpretation linking your observations to a concept (e.g., diffusion, sense of place, cultural ecology).

Cultural Geography: Conclusion

Cultural geography is a vital field for understanding the dynamic relationship between human culture and the physical world. By exploring topics like urban cultural landscapes, migration patterns, and regional traditions, this discipline reveals how geography influences cultural behaviors and identities. From the symbolism of sacred spaces to the challenges of preserving cultural heritage in an increasingly globalized world, cultural geography offers profound insights into the forces that shape our societies and environments. This knowledge is essential for addressing contemporary challenges, fostering cultural appreciation, and ensuring sustainable development in diverse and interconnected communities.

Cultural Geography – Frequently Asked Questions

What is Cultural Geography, and what does it study?

Cultural Geography studies how culture, identity, beliefs, practices, and values are shaped by—and in turn shape—the spaces, places, and environments people inhabit. It looks at how geography influences culture (through landscape, climate, migration, resources) and how cultural decisions transform places (through urban design, heritage, community spaces, borders, and globalisation).

How does Cultural Geography differ from physical geography or environmental science?

Unlike physical geography or environmental science, which focus on natural processes (like climate, geology, ecology), Cultural Geography emphasises human experiences, meaning, identity, and social relations embedded in space. It studies how people interpret and use places, how cultural practices vary across space, and how social, economic, political and historical factors influence landscapes and human-environment interactions.

What kinds of questions does Cultural Geography ask?

Questions include: How do migration, colonialism, trade, and globalisation affect the cultural identity of places? How do urbanisation and modern development change older cultural landscapes? How do people negotiate identity, memory, and heritage in multicultural or postcolonial contexts? How do diasporas or transnational communities maintain connections across space?

What methods does Cultural Geography use to study space and culture?

Cultural Geography employs methods such as field observation, ethnography, interviews, spatial mapping, GIS and digital mapping, archival research, historical cartography, and analysis of literature, art, and media. It often combines qualitative and quantitative approaches, allowing researchers to trace patterns, narratives, and spatial transformations over time and across regions.

Why is Cultural Geography important in a globalised world?

In a globalised world of migration, transnational identities, climate change, urban growth, and shifting borders, Cultural Geography helps us understand how global processes impact local identities and how communities adapt to change. It reveals how space, memory, heritage, displacement and belonging intersect, helping make sense of modern social, political, and environmental challenges.

What skills can I develop by studying Cultural Geography?

You can develop skills in spatial thinking, map reading, data interpretation, comparative cultural analysis, qualitative research, writing, and critical reflection. Understanding how geography and culture intertwine equips you to analyse urban planning, migration, heritage, environmental justice, globalisation, and social policy in context.

How does Cultural Geography connect with history, anthropology, or cultural studies?

Cultural Geography overlaps significantly with history, anthropology, cultural studies, sociology, urban planning, and environmental studies. It traces how cultural practices evolve in place and time, how societies adapt to physical environment, how migrations and exchanges change landscapes, and how identity, memory, and belonging are tied to land, architecture, and spatial organisation.

What kind of topics might be covered in a Cultural Geography module at university?

Topics may include urbanisation and city cultures, migration and diaspora, heritage and memory, national and regional identity, borderlands and postcolonial space, human-environment interactions, globalisation and localisation, spatial inequality, landscapes of conflict or reconciliation, and digital mapping and spatial media studies.

How is Cultural Geography typically assessed?

Assessment often includes essays, case studies, map-based assignments, spatial analysis, fieldwork reports, presentations, and sometimes community or development projects. You may be asked to interpret spatial data, reflect on cultural landscapes, analyse migration patterns, or compare regions historically and socially.

What career paths can Cultural Geography lead to?

Cultural Geography graduates may work in urban and regional planning, heritage and conservation, NGO and development work, environmental and human-rights advocacy, migration and refugee support, social research, cultural resource management, policy analysis, journalism, GIS analysis, tourism, and community development roles requiring spatial-cultural understanding.

How can I prepare now if I want to study Cultural Geography at university?

You can start by exploring maps — historical, cultural, and social. Read about migration, cities, heritage, and globalisation. Visit places with layered histories, reflect on how space and memory overlap, follow relevant documentaries or articles, and practise writing reflections on your observations. Getting comfortable with spatial thinking and cultural context will give you a head start.

Cultural Geography: Review Questions and Answers:

1. What is cultural geography and how does it differ from physical geography?

Answer: Cultural geography is the study of how human culture interacts with and shapes the physical environment, focusing on aspects such as identity, language, and social practices that are tied to specific places. It differs from physical geography, which concentrates on the natural features and processes of the earth, like climate and landforms. Cultural geographers analyze how cultural values and social behaviors are influenced by the geographical context and vice versa. This interdisciplinary approach helps to illuminate the dynamic relationships between people and their environments, providing a nuanced understanding of both cultural expression and spatial organization.

2. How do cultural geographers use historical analysis in their research?

Answer: Cultural geographers use historical analysis to trace the evolution of cultural landscapes and understand how past events have shaped present-day social and spatial patterns. They examine archival documents, maps, and artifacts to reconstruct the historical context of a place, revealing how cultural identities and social structures have developed over time. This method allows researchers to identify long-term trends and the influence of historical processes on cultural practices. By situating contemporary cultural phenomena within a historical framework, cultural geographers can better interpret changes in identity and the significance of place in shaping human experience.

3. What methodologies are commonly employed in cultural geography studies?

Answer: Cultural geography studies commonly employ qualitative methodologies such as ethnography, participant observation, and in-depth interviews, along with spatial analysis using GIS (Geographic Information Systems). These methods allow researchers to gather rich, contextual data about how individuals and communities interact with their environments. They combine fieldwork with theoretical analysis to interpret the meanings attached to places and cultural practices. This mixed-method approach provides a comprehensive understanding of the complex interplay between culture and geography, revealing both the subjective experiences and objective patterns that define human landscapes.

4. How does the concept of “place” influence cultural identity according to cultural geography?

Answer: The concept of “place” is central to cultural geography because it embodies the physical and symbolic environments that shape personal and collective identities. Places provide a sense of belonging and continuity, influencing how individuals perceive themselves and relate to others within a community. Cultural geographers argue that the unique characteristics of a place—its history, landscape, and cultural practices—contribute to the formation of identity and social cohesion. This understanding underscores the importance of preserving local heritage and recognizing the role of geography in the continuous evolution of culture.

5. What role do maps and spatial analysis play in cultural geography?

Answer: Maps and spatial analysis are critical tools in cultural geography as they visually represent the distribution and relationships of cultural phenomena across different regions. By using Geographic Information Systems (GIS), researchers can analyze spatial patterns and visualize data such as population distribution, cultural landmarks, and migration flows. These visualizations help to reveal correlations between cultural practices and geographic factors, offering insights into how space influences social behavior. Maps serve not only as analytical tools but also as means of communicating complex cultural and historical information in an accessible format.

6. How do cultural geographers address the impact of globalization on local cultures?

Answer: Cultural geographers address the impact of globalization on local cultures by examining the ways in which global flows of information, people, and commodities influence cultural practices and identities. They explore how traditional cultural expressions are transformed or hybridized in the context of global interactions, and how local communities adapt to external influences. This research often involves comparing local cultural practices before and after globalization to assess changes in identity and social structure. By highlighting both the challenges and opportunities presented by globalization, cultural geographers provide a nuanced understanding of cultural resilience and transformation.

7. What is the significance of fieldwork in cultural geography?

Answer: Fieldwork is a cornerstone of cultural geography because it enables researchers to immerse themselves in the environments they study and to gather firsthand data on cultural practices and spatial relationships. Through participant observation, interviews, and direct engagement with communities, cultural geographers can capture the lived experiences and perceptions of the people in a specific place. This method provides rich, contextual insights that are essential for understanding the complex interactions between culture and geography. Fieldwork not only enriches the research findings but also fosters a deeper, empathetic connection with the subjects under study.

8. How does cultural geography contribute to our understanding of migration and urban development?

Answer: Cultural geography contributes to our understanding of migration and urban development by examining the spatial patterns and cultural dynamics that drive population movements and the growth of cities. It analyzes how migrants bring their cultural practices with them, influencing urban landscapes and reshaping social identities. This field explores the tensions and synergies between different cultural groups in urban settings, revealing how diverse communities negotiate space and identity. By linking migration patterns with urban development, cultural geography provides valuable insights into the challenges and opportunities of multicultural urban environments.

9. How can cultural geography help in preserving local heritage and promoting sustainable development?

Answer: Cultural geography helps in preserving local heritage by documenting and analyzing the unique cultural practices and landscapes that define a community’s identity. It offers strategies for protecting historical sites, traditional practices, and indigenous knowledge against the pressures of modernization and globalization. By understanding the deep connections between culture and place, policymakers and community leaders can develop sustainable development plans that respect and incorporate local heritage. This integrated approach ensures that development initiatives are culturally sensitive and promote long-term environmental and social sustainability.

10. How does cultural geography explain the relationship between landscape and power dynamics in society?

Answer: Cultural geography explains the relationship between landscape and power dynamics by exploring how physical spaces are used to exert control and influence over populations. It examines how the design, organization, and symbolism of landscapes reflect and reinforce social hierarchies, political authority, and cultural values. Through spatial analysis, cultural geographers reveal how urban planning, architectural design, and public spaces can either democratize or concentrate power within a society. This critical perspective highlights the interplay between the built environment and societal structures, providing insights into the ways in which geography shapes and is shaped by power relations.

Key Maps to Master

- Language Families & Scripts: where writing systems cluster and overlap.

- Religious Regions & Pilgrimage Routes: sacred corridors and contested sites.

- Migration Corridors: seasonal, circular, and long-distance flows.

- Urban Morphology: CBDs, waterfronts, ethnic enclaves, creative districts.

- Heritage & Tourism Networks: routes linking museums, monuments, and festivals.

Cultural Geography: Thought-Provoking Questions and Answers

1. How might digital mapping technologies reshape our understanding of cultural landscapes?

Answer:

Digital mapping technologies, such as Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and satellite imagery, are transforming the way we study cultural landscapes by providing dynamic and interactive visualizations of spatial data. These tools enable researchers to overlay historical maps with current geographic data, revealing changes in cultural patterns, urban development, and environmental impacts over time. By harnessing digital mapping, scholars can conduct comparative studies that trace the evolution of cultural spaces, uncovering correlations between physical geography and cultural expression. This innovative approach not only enhances the precision of spatial analysis but also makes cultural research more accessible to a broader audience through interactive digital platforms.

Furthermore, digital mapping facilitates real-time monitoring and data collection, allowing cultural geographers to capture transient phenomena and rapidly changing landscapes. The integration of user-generated content and social media data further enriches these maps, providing a more comprehensive picture of contemporary cultural dynamics. As these technologies continue to evolve, they are likely to redefine traditional methodologies in cultural geography, opening up new avenues for research and public engagement in the study of cultural heritage.

2. In what ways can cultural geography inform urban planning and sustainable development policies?

Answer:

Cultural geography can inform urban planning and sustainable development policies by providing insights into the cultural significance of spaces and the social dynamics that shape urban environments. By analyzing how communities interact with their physical surroundings, cultural geographers can identify key cultural landmarks and areas of social importance that should be preserved or integrated into development plans. This understanding helps planners design urban spaces that not only accommodate growth but also respect cultural heritage and promote community identity. Such an approach leads to more inclusive and resilient cities that balance economic development with social and cultural sustainability.

Moreover, cultural geography highlights the role of public spaces in fostering social cohesion and cultural exchange, which are essential for vibrant urban life. Policymakers can use these insights to create policies that enhance access to cultural amenities, promote public art, and support community-based initiatives. By incorporating cultural perspectives into urban planning, cities can become more livable, equitable, and reflective of the diverse identities of their inhabitants. This integration ultimately supports long-term sustainability by ensuring that development initiatives align with the cultural and social needs of communities.

3. How might globalization influence the cultural geography of a region, and what are the implications for local identities?

Answer:

Globalization influences the cultural geography of a region by facilitating the exchange of cultural ideas, practices, and economic opportunities that can reshape local identities. As global networks expand, regions experience an influx of diverse cultural influences that can lead to the blending of traditional and contemporary practices. This process often results in the emergence of hybrid cultural landscapes where local identities are continuously negotiated and redefined. The implications for local identities are profound, as communities may face both opportunities for cultural enrichment and challenges related to cultural homogenization or loss of traditional practices.

In addition, globalization can intensify competition for resources and cultural prominence, leading to tensions between preserving local heritage and embracing global trends. These dynamics force communities to negotiate their cultural boundaries, often resulting in innovative adaptations that reflect both global influences and local uniqueness. As such, globalization is a double-edged sword that can enhance cultural diversity while also challenging the continuity of local traditions. Understanding these processes is essential for developing policies that protect and promote local identities in an increasingly interconnected world.

4. How can cultural geography contribute to a deeper understanding of the social impact of historical events?

Answer:

Cultural geography contributes to a deeper understanding of the social impact of historical events by analyzing how these events shape the physical and cultural landscapes of societies. By examining spatial patterns, migration trends, and the distribution of cultural artifacts, cultural geographers can trace the long-term effects of historical events on community organization and identity. This approach reveals how historical events are inscribed in the landscape, influencing everything from urban development to regional dialects and traditions. Such insights help to contextualize historical narratives and understand their enduring influence on contemporary social structures.

Moreover, cultural geography allows for the exploration of how collective memory and cultural practices evolve in response to historical trauma and transformation. By studying the remnants of past events in the built environment and in cultural expressions, researchers can better comprehend the ways in which societies remember, reinterpret, and learn from their history. This multidimensional perspective not only enriches our understanding of historical impact but also informs contemporary discussions about cultural resilience and identity reconstruction in the aftermath of significant events.

5. In what ways can fieldwork in cultural geography uncover hidden aspects of cultural identity?

Answer:

Fieldwork in cultural geography uncovers hidden aspects of cultural identity by immersing researchers in the everyday lives of communities and enabling direct observation of cultural practices and spatial interactions. Through methods such as participant observation, interviews, and mapping, fieldwork captures the subtle nuances of how individuals relate to their environment and express their cultural identity. This hands-on approach allows researchers to document informal practices, local traditions, and the personal narratives that might be overlooked in more distant or theoretical studies. The rich, contextual data gathered through fieldwork provides a deeper understanding of the interplay between culture and space, revealing layers of meaning that are essential for comprehending complex social identities.

Furthermore, fieldwork fosters an empathetic connection between the researcher and the community, which can lead to more accurate and sensitive interpretations of cultural phenomena. By engaging directly with local populations, cultural geographers can gain insights into the symbolic significance of places and artifacts, as well as the challenges communities face in preserving their cultural heritage. This immersive research not only enriches academic knowledge but also empowers communities by validating their experiences and highlighting the importance of cultural continuity.

6. How might digital storytelling methods enrich the field of cultural geography?

Answer:

Digital storytelling methods enrich the field of cultural geography by providing innovative ways to capture and share the narratives of communities and their relationship with place. These methods allow researchers to compile multimedia content—such as video interviews, photographs, and interactive maps—to create compelling narratives that bring cultural experiences to life. Digital storytelling facilitates a more engaging and accessible form of documentation, enabling both academic and public audiences to connect with cultural histories on a personal level. This approach not only preserves the rich tapestry of local narratives but also democratizes access to cultural heritage by making it available online.

In addition, digital storytelling fosters interdisciplinary collaboration by integrating elements from journalism, filmmaking, and social media. This collaborative process encourages the sharing of diverse perspectives and can lead to a more nuanced understanding of how cultural identities are constructed and maintained over time. By leveraging digital platforms, cultural geographers can reach wider audiences, stimulate public dialogue, and contribute to the preservation of cultural memory in an increasingly digital world.

7. What are the implications of cultural borderlands for understanding identity and belonging?

Answer:

Cultural borderlands, which are regions where distinct cultural identities intersect and interact, offer rich implications for understanding identity and belonging. These borderlands are characterized by a blending of traditions, languages, and practices, resulting in hybrid cultural forms that challenge rigid notions of identity. Studying these spaces reveals how individuals negotiate their belonging in environments marked by diversity and tension, highlighting the fluid and dynamic nature of cultural identity. The concept of cultural borderlands underscores the idea that identity is not fixed but continually reshaped through interactions between different cultural influences.

Moreover, exploring cultural borderlands can shed light on issues of migration, conflict, and social integration, as these regions often serve as microcosms for broader societal dynamics. The insights gained from such studies can inform policies aimed at promoting social cohesion and cultural inclusion, as well as contribute to a deeper understanding of how communities adapt to and thrive amidst cultural diversity. Ultimately, cultural borderlands provide a valuable framework for examining the complexities of identity formation and the multifaceted nature of belonging in a globalized world.

8. How might the study of cultural landscapes inform debates on urbanization and environmental change?

Answer:

The study of cultural landscapes informs debates on urbanization and environmental change by revealing how human activities shape and are shaped by the physical environment. Cultural geographers analyze the modifications made to natural landscapes, such as urban development, agricultural practices, and infrastructure projects, to understand their impact on both culture and the ecosystem. This research provides critical insights into the ways in which cultural values and economic imperatives drive changes in the environment, as well as how these changes, in turn, affect social practices and cultural identity. By linking cultural heritage with environmental sustainability, scholars can advocate for more balanced and context-sensitive approaches to urban planning and ecological conservation.

Furthermore, examining cultural landscapes helps to highlight the tension between progress and preservation, offering a nuanced perspective on the trade-offs involved in urban expansion and industrial development. This research can inform policy debates by emphasizing the importance of preserving cultural and natural heritage in the face of rapid modernization. The insights provided by cultural geography thus contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the complex interplay between human society and the environment, which is essential for sustainable development strategies.

9. How can cultural geography be used to address issues of social inequality and marginalization?

Answer:

Cultural geography can be used to address issues of social inequality and marginalization by analyzing the spatial distribution of resources, services, and opportunities within communities. By mapping disparities in access to education, healthcare, and economic opportunities, cultural geographers can identify areas where marginalized groups are disproportionately affected. This spatial analysis provides a visual representation of inequality and highlights the social and environmental factors that contribute to disparities. Through detailed research, cultural geography can inform targeted interventions aimed at reducing social exclusion and promoting equitable development.

Additionally, cultural geographers study how marginalized communities navigate and negotiate their spatial environments, revealing strategies of resistance and resilience. These insights can be used to advocate for policy changes that address structural inequalities and enhance social inclusion. By integrating qualitative data with spatial analysis, cultural geography offers a powerful tool for understanding and addressing the root causes of social inequality, ultimately contributing to more just and equitable societies.

10. What impact does the commercialization of culture have on cultural landscapes and collective memory?

Answer:

The commercialization of culture impacts cultural landscapes and collective memory by transforming how cultural artifacts and traditions are produced, consumed, and remembered. Commercial interests often drive the creation and distribution of cultural products, which can lead to the commodification of heritage and the dilution of traditional values. This process can result in the erosion of local identities and the marginalization of less dominant cultural expressions. By prioritizing profit over preservation, commercialization may alter cultural landscapes, changing the way communities interact with and remember their past.

On the other hand, the commercialization of culture can also promote the dissemination of cultural heritage to wider audiences, potentially revitalizing interest in traditional practices. However, this exposure often comes at the cost of authenticity, as cultural elements are repackaged to appeal to mainstream markets. Cultural geography examines these dynamics to understand the balance between economic forces and cultural preservation, offering critical insights into how collective memory is shaped in contemporary society.

11. How might public policies aimed at heritage preservation benefit from insights provided by cultural geography?

Answer:

Public policies aimed at heritage preservation can benefit significantly from the insights provided by cultural geography, which examines the spatial and cultural dimensions of heritage. By mapping cultural landscapes and identifying areas of historical significance, cultural geographers provide empirical data that can guide the allocation of resources and the development of conservation strategies. These insights help policymakers understand the value of preserving not only tangible artifacts but also the cultural practices and social interactions that define a community’s identity. Such evidence-based policies can ensure that heritage preservation efforts are both effective and sustainable, balancing development with cultural conservation.

Moreover, cultural geography highlights the importance of local participation and community engagement in heritage preservation. It emphasizes the need for policies that are culturally sensitive and that reflect the unique values and needs of different regions. By incorporating these perspectives, public policies can create more inclusive and resilient frameworks for preserving cultural heritage, ultimately enriching the cultural fabric of society and fostering a deeper sense of collective memory.

12. How might emerging trends in digital humanities influence the future study of cultural history?

Answer:

Emerging trends in digital humanities are poised to transform the future study of cultural history by providing innovative tools for data collection, analysis, and visualization. Digital humanities methodologies, such as text mining, network analysis, and digital mapping, enable researchers to analyze vast datasets and uncover patterns that were previously difficult to detect. These tools not only enhance the precision and depth of historical research but also make cultural history more accessible to a broader audience through interactive digital platforms. As a result, the integration of digital techniques in cultural history can lead to new interpretations and a more comprehensive understanding of cultural phenomena.

Furthermore, digital humanities fosters interdisciplinary collaboration by bridging the gap between traditional historical methods and modern technology. This convergence of techniques encourages innovative research approaches that combine quantitative and qualitative analysis, providing a richer, multifaceted perspective on cultural history. The continued evolution of digital tools will likely drive significant shifts in how scholars study and disseminate historical knowledge, ensuring that the field remains dynamic, inclusive, and responsive to the challenges of the digital age.

Last updated: