Media and communication history offers a vital lens through which we can understand not only the evolution of technology and information but also the shifting social, cultural, and political dynamics of human civilization. The trajectory of communication—from oral storytelling to the printing press, radio, television, and the internet—has influenced how ideas are shared, authority is exercised, and culture is transmitted. This field overlaps with inquiries into history of ideas, where media serves as the carrier of philosophical, political, and aesthetic thought across generations.

The role of communication in shaping governance and collective behavior becomes clear when examining the history of political systems and how these systems depended on and were reshaped by advances in communication. Just as the Enlightenment relied on pamphlets and books to spread reformist ideals, modern political movements have leveraged mass media and social platforms. The evolution of communication closely ties to the spread of social movements and the formation of ideological coalitions seen in the diplomatic history of nation-states.

The media has historically reinforced or challenged dominant cultural narratives. This is evident in the study of popular culture and postcolonial cultural studies, which explore how imagery, language, and storytelling have contributed to both the maintenance of power and its resistance. Understanding the dissemination of belief systems is also central to religious and spiritual history, where sacred texts and oral traditions shaped societies long before the digital age.

The economic underpinnings of media are explored through fields like economic history and financial history, which examine the funding models, ownership structures, and regulatory regimes that influence content production. Additionally, insights from economic thought and theory help explain the commodification of information. The reach and role of communication in shaping conflict is evident in economic history of warfare and guerrilla warfare and insurgency studies, where propaganda and psychological operations were pivotal tools.

Electoral processes too have been transformed by communication strategies, as seen in electoral history, electoral fraud and integrity, and electoral systems and political parties. These areas highlight how the press, radio, and digital media have become central to campaigns, voter education, and manipulation alike. Communication has also played a decisive role in shaping revolutionary constitutions and post-colonial constitutionalism, where public discourse shaped new political identities.

In parallel, the figures chronicled in diplomatic personalities and economic diplomacy reflect how the mastery of rhetoric, persuasion, and mass communication were essential to international negotiations. These threads come together within the broader umbrella of history, illuminating the multidisciplinary nature of communication studies. Finally, disciplines such as education history and history of political economy show how educational systems and public institutions leveraged communication as a tool for social control and empowerment.

This illustration captures the historical journey of media and communication across centuries. On the left, early technologies such as the printing press, newspapers, and radio represent the foundations of mass communication. Toward the center, television and satellite broadcasting symbolize the rise of global audiences. On the right, smartphones, social media platforms, data streams, and digital icons illustrate the contemporary world of instant connectivity. People interacting with devices throughout the scene emphasize how media shapes everyday life, identity, culture, and power. Together, the image reflects the core theme of media and communication history: that each technological shift transforms how societies think, relate, and share meaning across the world.

Table of Contents

Key Focus Areas in Media and Communication History

1. Evolution of Media Technologies

The history of media unfolds as overlapping waves—not a simple replacement. New tools sit atop older ones, creating hybrid “media ecologies.”

Orality & Writing

- Oral cultures: epics, performance, and memory techniques (bards, griots) maintain law and identity.

- Writing systems: cuneiform, papyrus, parchment, paper; the codex reorganizes reading into pages, indexes, and citation.

Print & Postal Networks

- Movable type: Gutenberg enables cheap duplication; vernacular Bibles, pamphlets, newspapers.

- Print capitalism: standardized languages and markets; postal routes and newsbooks create early information infrastructures.

Telegraph, Telephone & Photography

- Telegraph (1840s): separates message from messenger; news agencies (Reuters, AP) globalize information.

- Telephone (1870s): synchronous voice at distance; switchboards and operator labor.

- Photography: new evidentiary claims (crime, science, war reporting).

Film, Radio & Phonograph

- Film: from actualités to feature narratives; star system; national cinemas and propaganda newsreels.

- Radio: live voice/music; public-service vs. commercial models; wartime leadership and morale.

- Recorded sound: music industries, formats (shellac → vinyl → cassette → digital).

Television & Satellites

- Broadcast TV: domestic screens; network era programming; event television (moon landing, Olympics).

- Satellite links: live global feeds, 24-hour news channels.

Digital Networks & Platforms

- Internet & Web: from ARPANET to browsers; search engines; email and forums.

- Social media & mobile: participatory culture, creator economies, messaging apps.

- Streaming & cloud: on-demand audio/video; binge viewing; recommendation systems.

- AI & synthetic media: generative images/text, deepfakes, and watermarking standards.

2. Media’s Role in Shaping Cultural Dynamics

Media narrate who “we” are by selecting voices, images, and rhythms that become shared memory.

Press, Publics & Counterpublics

- Newspapers & coffeehouses: expand debate and critique; penny press broadens readership.

- Counterpublics: abolitionist, suffragist, labor, and diasporic presses create alternative spheres.

Nation, Identity & Popular Culture

- Imagined communities: synchronized reading/listening builds national time (holidays, results nights).

- Glocal flows: Bollywood, K-pop, telenovelas travel and localize; memes remix global symbols.

- Fan cultures: zines to online fandoms; participatory authorship and canon disputes.

Regulation & Censorship

- Licensing, obscenity, blasphemy, and sedition laws; ratings systems; platform policy and takedowns.

- Chilling effects and the “Streisand effect” when suppression amplifies attention.

3. Political and Social Impact of Media

Communication infrastructures enable movements, states, and markets to coordinate action.

Revolution & Reform

- Pamphlets in the Atlantic revolutions; samizdat in late-Soviet contexts; SMS in the Philippines (2001) mobilizations.

- Hashtag activism (#MeToo, #BlackLivesMatter) connects testimony to visibility and policy debates.

Journalism & Democracy

- Accountability: watchdog investigations, FOI laws, whistleblowing platforms.

- Challenges: dis/misinformation, filter bubbles, state capture, safety of journalists.

- Verification: OSINT, geolocation, reverse image search, and data journalism.

Propaganda, Persuasion & PSYOPS

- State and corporate persuasion across posters, newsreels, radio, TV, and micro-targeted ads.

- Media literacy and prebunking/inoculation strategies reduce manipulation.

3. Political and Social Impact of Media

Communication infrastructures enable movements, states, and markets to coordinate action.

Revolution & Reform

- Pamphlets in the Atlantic revolutions; samizdat in late-Soviet contexts; SMS in the Philippines (2001) mobilizations.

- Hashtag activism (#MeToo, #BlackLivesMatter) connects testimony to visibility and policy debates.

Journalism & Democracy

- Accountability: watchdog investigations, FOI laws, whistleblowing platforms.

- Challenges: dis/misinformation, filter bubbles, state capture, safety of journalists.

- Verification: OSINT, geolocation, reverse image search, and data journalism.

Propaganda, Persuasion & PSYOPS

- State and corporate persuasion across posters, newsreels, radio, TV, and micro-targeted ads.

- Media literacy and prebunking/inoculation strategies reduce manipulation.

4. The Business of Media

Revenue models shape what gets made, seen, and remembered.

Legacy Models

- Advertising-supported: newspapers, radio, broadcast TV; audience ratings and prime time.

- License-fee / public service: independent from advertisers but accountable to public mandates.

- Patronage & philanthropy: early journals, documentary funds, grants.

Digital Monetization

- Subscriptions & paywalls: bundles, freemium; churn management and newsletters.

- Platforms: revenue shares, creator funds, tipping, affiliate links.

- Data & ads: programmatic auctions, third-party cookies, contextual vs. behavioral targeting.

- Ethical tensions: clickbait incentives, engagement bias, dark patterns, data brokers.

5. The Role of Technology in Transforming Media

From formats to protocols, technical choices encode values about speed, access, and control.

Print & Reproduction

- Offset and rotary presses; linotype; photo-typesetting; desktop publishing; print-on-demand.

Transmission & Storage

- Telegraph/telephone copper → fiber optics; radio spectrum allocation; satellite constellations.

- Tape, optical discs, solid-state drives; codecs (MP3, H.264/265, AV1) and compression trade-offs.

Computation & Algorithms

- Search indexing, recommender systems, ranking, and moderation pipelines.

- Watermarking/signed provenance, content authenticity initiatives, and synthetic-media detection.

Examples in Media and Communication History

Each case pairs context, media system, techniques, and impact—plus a short activity you can run in class or for revision.

1) Propaganda in Wartime

- Context: Total war requires mass mobilization, compliance, and morale management.

- Media systems: posters, newsreels, radio addresses, controlled press, later TV.

- Techniques: bandwagon appeals, fear/hope contrasts, stereotypes, heroization, carefully staged “live” messages.

- Examples:

- World War II: Churchill’s BBC broadcasts; U.S. Office of War Information; Goebbels’ Newsreel & radio orchestration; Soviet photo essays.

- Cold War: Voice of America/Radio Free Europe vs. state broadcasters; missile gap narratives; televised crises (Cuban Missile Crisis).

- Impact: Aligns civilian behavior (rationing, enlistment); normalizes exceptional measures; creates enduring national myths.

- Mini-activity: Choose one poster and one radio clip. Identify the emotion each targets and the behavior it seeks; rewrite a neutral caption that preserves facts but reduces manipulation.

2) The Printing Press & the Reformation

- Context: 16th-century Europe—religious authority contested amid rising literacy.

- Media systems: movable type, vernacular pamphlets, broadsides, woodcuts, postal routes.

- Techniques: short formats, vivid images, satire; translation accelerates uptake; reprinting across cities.

- Examples: Luther’s 95 Theses; pamphlet wars; vernacular Bibles; cheap song pamphlets spreading doctrine as melody.

- Impact: Decentralizes interpretation, boosts lay literacy, reshapes church–state relations, seeds the idea of a public of readers.

- Mini-activity: Compare one Catholic and one Protestant broadside on the same issue; list rhetorical differences in 5 lines.

3) Television & the Public Event

- Context: Domestic screens synchronize national attention and emotion.

- Media systems: network-era TV, live satellite links, later 24-hour cable news.

- Techniques: staging for the camera, split screens, anchors as national narrators, breaking-news graphics.

- Examples:

- 1960 Kennedy–Nixon debates: appearance and televisual style shape perceptions of competence.

- Apollo 11 (1969): global live broadcast creates a planetary audience moment.

- Gulf War (1991): real-time strikes inaugurate the 24-hour “CNN effect.”

- Impact: Politicians adopt TV logic; crisis coverage compresses deliberation; advertising and ratings influence story choice.

- Mini-activity: Watch a 2-minute debate clip muted, then with audio only. Note how visual vs. verbal cues alter your judgment.

4) Social Media & Movements

- Context: Networked publics coordinate beyond legacy gatekeepers.

- Media systems: Facebook events, Twitter/X hashtags, YouTube livestreams, Instagram/TikTok stories.

- Techniques: testimonial threads, viral visuals, hashtag framing, livestream verification, mutual-aid spreadsheets.

- Examples:

- Arab Spring (2010–2012): coordination, documentation, international visibility; hybrid with on-ground organizing and satellite TV.

- #MeToo / #BLM: everyday testimony turns private harm into public claim; platforms as evidence archives.

- Impact: Rapid agenda-setting; counter-mobilization and disinformation also scale; platform rules become de facto public policy.

- Mini-activity: Trace one hashtag’s lifecycle (origin → peak → policy/media response) in 6 timestamps with sources.

5) Photojournalism & War

- Context: Portable cameras shift witness from official communiqués to images with high affective charge.

- Media systems: wire services, picture magazines, TV, later digital platforms.

- Examples: Vietnam (napalm girl, Saigon execution), Fallujah images, cellphone footage from recent conflicts.

- Ethics: dignity vs. shock, consent, retraumatization; staging/propaganda risks; need for provenance and context.

- Impact: Images catalyze protest and policy debate; also fuel misinformation if decontextualized.

- Mini-activity: Run a 5-step verification (source, date, location, edits, original caption) on a widely shared war image; write a 120-word context card.

6) Telegraph & the Birth of Global News

- Context: 19th-century cables compress time; markets and empires demand rapid info.

- Media systems: telegraph networks, press agencies (Reuters, AP, Havas), standardized wire style.

- Impact: Inverted-pyramid writing emerges; “objectivity” ideal rises with syndication; geopolitical bias travels with cable ownership.

- Mini-activity: Edit a long report into a 120-word wire; note what nuance is lost and how headlines steer interpretation.

7) Samizdat, Fax & Photocopiers

- Context: Under censorship, duplication tech enables parallel publics.

- Media systems: carbon copies, mimeographs, photocopiers, fax networks.

- Examples: Soviet samizdat literature; faxed protest calls and newspapers during late-20th-century crises.

- Impact: Trust moves through small, verified networks; shows how “old” tech can outflank surveillance.

- Mini-activity: Design a one-page samizdat: choose a topic, add safety measures (no names, routing), and a distribution tree.

8) Pirate Radio & Music Scenes

- Context: Youth cultures and marginalized communities bypass formal licenses.

- Media systems: offshore ships, rooftop transmitters, community radio.

- Impact: Breaks new genres; forces regulatory change; builds place-based identity.

- Mini-activity: Schedule a 1-hour pirate block: 4 segments + 2 community notices; explain how it serves a counterpublic.

9) Indymedia, Blogs & Citizen Journalism

- Context: Turn of the millennium anti-globalization protests and cheap web publishing.

- Media systems: open publishing sites, RSS blogs, email lists, early forums.

- Impact: Live updates challenge mainstream frames; verification norms evolve (link culture, corrections, comments).

- Mini-activity: Convert a 600-word blog post into a 6-tweet/thread summary with 2 primary links and one caveat.

10) Messaging Apps, Rumor & Verification

- Context: Encrypted or closed-group messaging (WhatsApp, Telegram, WeChat) becomes default news for many.

- Media systems: end-to-end encryption, forwards, voice notes, stickers, local language audio.

- Challenges: rapid rumor spread; micro-targeted mobilization; limited visibility for fact-checkers.

- Counter-measures: forward limits, image hash-matching, community fact-check hotlines, prebunking campaigns, media-literacy micro-lessons.

- Mini-activity: Draft a 90-second voice-note “prebunk” for a recurring local rumor; include one checkable fact and one action.

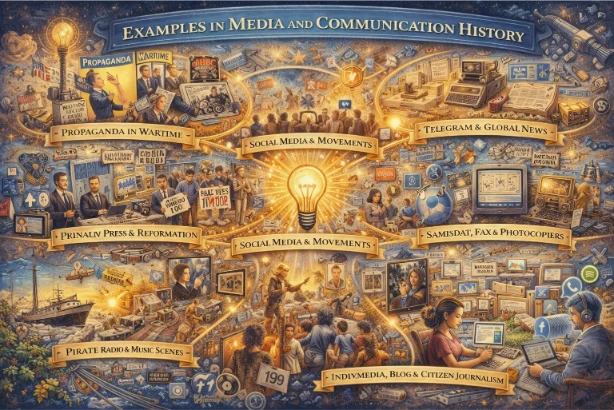

This richly detailed illustration brings together pivotal moments in the history of media and communication. It visually connects the printing press and the Reformation, wartime propaganda, the rise of television, telegraph networks, citizen journalism, pirate radio, and today’s social media movements. At the center, a glowing lightbulb symbolizes the power of ideas and public discourse, while surrounding scenes show how technologies, institutions, and ordinary people have shaped—and been shaped by—communication systems. The image reinforces the central theme of the page: media is not just a tool, but a powerful force that shapes culture, politics, identity, and collective memory across time.

Applications of Media and Communication History

1. Understanding Cultural Evolution

- Explains how formats and infrastructures shape memory, language standardization, and taste communities.

- Traces continuity: podcasts inherit from radio; newsletters from pamphlets; shorts from vaudeville and vines.

2. Informing Media Literacy

- Source evaluation, provenance, prebunking/inoculation against manipulation.

- Recognize affordances and incentives behind interfaces (infinite scroll, autoplay, streaks).

3. Shaping Policy & Regulation

- Historic rationales for free speech, public interest obligations, spectrum allocation, and privacy norms.

- Design of platform rules: transparency reporting, auditability, data minimization, and child protections.

4. Design & Product Practice

- Translate lessons from past harms (radio panics, yellow journalism, disinfo campaigns) into UX safeguards and content standards.

Research Methods & Sources

- Archives: newspapers, broadcast scripts, program logs, ad agency books, platform transparency reports.

- Oral history & ethnography: reporters, producers, moderators, creators, audience communities.

- Quantitative analysis: content coding, network mapping, rating data, engagement metrics.

- Digital tools: web archives (Wayback), reverse image search, OCR pipelines, dataset notebooks.

Mini-Labs

- Front-page audit: compare two newspaper front pages (different decades). Identify framing devices and ad/news ratios.

- Algorithm diary (48h): log 30 items served to you; infer likely signals; propose one design change to diversify feed.

- Provenance check: take a viral image, trace first upload, context, and edits; write a 150-word verification note.

Key Terms Glossary

- Public sphere: arenas where citizens discuss common concerns.

- Counterpublic: communicative spaces for marginalized groups.

- Gatekeeping: selection and prioritization of information.

- Agenda-setting: media influence on what audiences think about.

- Framing: how issues are presented to shape interpretation.

- Attention economy: competition for finite human focus.

- Platformization: shift of cultural production and distribution onto interoperable, data-driven platforms.

- OSINT: open-source intelligence techniques for verification.

- Provenance: verifiable history of creation and edits.

Assessment & Projects

- Comparative essay (1,500 words): “From pamphlet to platform: how distribution changes dissent.”

- Interactive timeline: five milestone technologies with 100-word captions and primary-source links.

- Policy brief (800 words): propose a platform transparency rule; include historical precedent and implementation risks.

- Podcast (6–8 min): produce an episode on one local media archive; include two sourced audio clips and credits.

Why Study Media and Communication History

Media and communication history is not just a chronology of gadgets and platforms. It is a toolkit for understanding how power, culture, and technology shape what can be said, who can speak, and what publics can hear. Studying it equips you to interrogate interfaces and institutions, to trace ideas across time and space, and to design communication that is effective, ethical, and inclusive.

1) Intellectual Payoffs

- Contextual thinking: place today’s platforms (feeds, streams, DMs) within longer arcs from orality to print to broadcast to digital—seeing continuities as well as disruption.

- Conceptual clarity: differentiate information, knowledge, propaganda, publicity, rumor, and news; parse agenda-setting, framing, gatekeeping, and platformization.

- Systems lens: analyze media as socio-technical systems (standards, protocols, labor, regulation), not just content streams.

- Comparative method: learn to contrast media regimes (public service vs. commercial; centralized vs. decentralized; oral vs. literate cultures).

2) Civic & Ethical Payoffs

- Democratic judgement: evaluate sources, trace provenance, and weigh evidence; understand how investigative journalism and transparency norms evolved.

- Resilience to manipulation: recognize historical techniques of persuasion (from pamphlet wars to micro-targeted ads) and modern defenses (prebunking, media literacy, authenticity standards).

- Rights & responsibilities: balance free expression, privacy, and safety by studying why speech rules and privacy protections were created in the first place.

- Inclusion by design: learn from histories of exclusion (gendered/racialized audiences, disability access) to build accessible, multilingual, equitable communication.

3) Creative, Design & Product Payoffs

- Storycraft with memory: reuse proven narrative forms (serials, newsreels, soap arcs, explainer graphics) with modern tools.

- Audience insight: read ratings, circulation, and engagement as historically shaped signals—avoid short-term click-metrics traps.

- Safety by default: translate past harms (yellow journalism, radio panics, propaganda) into product requirements (rate-limits, labels, provenance, context windows).

- Experiment with form: prototype newsletters, podcasts, visual essays, and interactives that borrow from earlier media ecologies.

4) Global & Decolonial Perspectives

- Multiple modernities: examine how press, radio, cinema, and mobiles developed outside Euro-Atlantic centers (vernacular print, community radio, Nollywood, K-pop).

- Empire & resistance: track censorship, counterpublics, and diaspora media; see how communication infrastructures supported both domination and dissent.

- Translation & circulation: follow concepts as they move across languages and platforms; understand adaptation, dubbing, subtitling, and meme remix as historical practices.

5) Methods You’ll Master

- Archival research: newspapers, program logs, ad books, posters, broadcast scripts, oral histories.

- Forensic reading: source verification (OSINT), image metadata, reverse-search, timeline reconstruction.

- Data & networks: content coding, audience metrics, influence graphs, bibliometrics, citation trails.

- Design ethnography: observe how people actually use media; map affordances, friction, and unintended consequences.

6) Skills → Careers (What transfers where?)

| Skill | You’ll Practice | Fits Roles In |

|---|---|---|

| Evidence assessment | Provenance checks, bias auditing, contextualization | Journalism, policy analysis, trust & safety, research |

| Narrative design | Serial structure, arc planning, visual rhetoric | Content strategy, documentary, marketing, education |

| Data literacy | Metrics critique, dashboards, sampling limits | Analytics, product, audience development |

| Design ethics | Risk mapping, safety requirements, consent by design | UX, policy, civic tech, platform governance |

| Cross-cultural fluency | Localization, translation histories, comparative media | Global comms, diplomacy, NGOs, entertainment |

7) Mini-Studios (fast, high-value exercises)

- Front-page archaeology (40 min): Compare two front pages from different decades. Identify framing, layout hierarchy, and ad/news ratios. Produce a 120-word brief on how design guided attention.

- Algorithm diary (48 h): Log 30 items from your feed. Infer likely signals and surface one bias. Draft a one-sentence intervention that improves diversity without killing relevance.

- Provenance chain (30 min): Pick a viral image or quote. Trace earliest upload, edits, and context. Write a 150-word verification note with links and a confidence rating.

- Format remake (2 h): Adapt a historical form (pamphlet, newsreel, radio PSA) into a modern short or carousel. Explain why the form still works.

8) Portfolio & Impact

- Idea briefs: 3 x 500-word explainers that translate a complex communication problem for a public audience, each tied to a historical precedent.

- Interactive timeline: map one topic (e.g., “election coverage”) across five media eras with 100-word captions and primary-source links.

- Design memo: propose one product change (labels, provenance, friction) that addresses a known historical harm; include risk/benefit trade-offs.

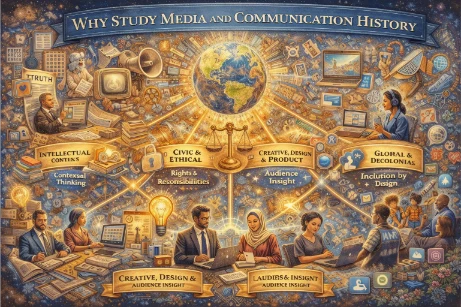

This illustration visualizes the long journey of human communication, from early print culture and broadcast media to today’s digital networks. At the center, a glowing globe represents shared public space, while surrounding symbols—books, radios, television screens, laptops, phones, data icons, and networks—show how technologies shape attention, trust, and influence. People from diverse backgrounds engage in reading, analyzing, designing, and discussing information, highlighting key themes of media history: critical judgment, ethical responsibility, cultural inclusion, and creative communication. The image reinforces the idea that studying media history equips learners to understand power, interpret messages, and build more thoughtful communication systems for the future.

Conclusion

From sung epics and carved tablets to fiber optics and generative models, media are more than delivery channels. They organize attention, authorize voices, and bind communities into shared time. Tracing these histories shows that each “new” medium inherits forms from the old, reorganizes power, and invites fresh responsibilities for makers, regulators, and audiences.

What the Long View Teaches

- Continuity inside change: New media rarely erase predecessors; they layer on top of them (radio → podcast, pamphlet → newsletter, newsreel → short video), carrying forward genres, habits, and biases.

- Infrastructures matter: Standards, spectrum, cables, app stores, and algorithms are the hidden constitution of public life; whoever sets them shapes who can speak and be heard.

- Power is communicative: Censorship, propaganda, and public-interest obligations evolve together. Democratic resilience depends on verifiable provenance, plural voices, and accountable institutions.

- Audiences are makers: From letters to the editor to fandoms and hashtag publics, people don’t just consume—they co-author culture and policy.

Paradoxes to Keep in View

- Speed vs. verification: The faster a message travels, the more design must slow it at key points (labels, context, friction) to preserve truth and trust.

- Openness vs. harm: Expanding participation demands smarter protections (safety by default, privacy by design) that don’t silence the vulnerable.

- Global reach vs. local meaning: Translation and recommendation extend stories worldwide, but credibility and care remain local and contextual.

- Metrics vs. mission: Attention is measurable; value is not. Healthy systems align incentives with civic and cultural goals.

Principles for Better Media Systems

- Provenance & authenticity: embed verifiable trails for images, audio, and text; make edits and sources transparent.

- Context on demand: surface explainers, timelines, and counterpoints at the point of consumption.

- Diverse discovery: design recommendation windows that periodically widen beyond the filter bubble.

- Safety & dignity: protect targets of harassment; reduce amplification of coordinated manipulation; prioritize accessibility.

- Public interest obligations: support archiving, data access for researchers, and independent audits of systems that shape attention.

How to Use This History—Right Now

- As a designer: convert past failures (yellow journalism, radio panics, disinformation waves) into product requirements (rate limits, circuit breakers, prominence for corrections).

- As a journalist/creator: borrow durable forms (serials, explainer cards, PSAs) and pair them with strong verification and source notes.

- As a policymaker/educator: ground rules and curricula in historical rationales so they’re principled, teachable, and resilient to backlash.

- As a citizen: practice provenance checks, reward outlets that correct themselves, and support institutions that keep memory and accountability alive.

Questions to Carry Forward

- What should every high-reach system owe the public that uses it?

- How can recommendation engines honor minority voices without becoming noise machines?

- Which parts of the communicative commons must be public, audited, and archived—and by whom?

- How do we design for disagreement so that pluralism becomes a feature, not a failure?

Media and Communication History – Frequently Asked Questions

What is Media and Communication History?

Media and Communication History studies how different media technologies and communication practices have developed over time, and how they have shaped culture, politics, and everyday life. It traces the evolution from oral traditions, manuscripts, and print to radio, film, television, digital platforms, and social media, asking how each medium reorganises who can speak, who can be heard, and what counts as public knowledge.

How does Media and Communication History differ from general Media Studies?

Media Studies often focuses on analysing contemporary content, audiences, and industries. Media and Communication History places stronger emphasis on long-term change. It asks how earlier media systems worked, how people responded to “new” technologies in their own time, and how past debates about censorship, propaganda, entertainment, or privacy anticipate current concerns about digital platforms and algorithms.

What kinds of media are examined in Media and Communication History?

The field covers a wide range of media: oral storytelling, handwritten manuscripts, printing presses, newspapers, magazines, photography, telegraphy, radio, cinema, television, telephony, the internet, and social media. It also considers communication infrastructures such as postal systems, satellites, undersea cables, and data centres, treating them as part of the history of communication.

What key questions are asked in Media and Communication History?

Key questions include: How did a new medium emerge and who controlled it? How did it change the speed and reach of communication? How did it affect power relations between governments, corporations, and citizens? Which voices were amplified or silenced? How did media shape identities, emotions, and everyday routines? And how did audiences interpret and sometimes resist media messages?

What sources are used to study Media and Communication History?

Historians draw on newspapers and magazines, broadcasting archives, advertising, films, radio and television programmes, corporate records, government documents, audience letters, fan communities, photographs, diaries, oral histories, and, increasingly, born-digital sources such as websites, blogs, and social media posts. They also use trade journals, technical manuals, and policy reports to understand how media systems were built and regulated.

How does technological change feature in Media and Communication History?

Technological change is important, but it is never treated as the only driver. Media and Communication History examines how new technologies interact with existing social structures, economic interests, cultural expectations, and political struggles. Rather than assuming that a device automatically transforms society, it asks who uses it, under what conditions, and with what consequences for access, inequality, and control over information.

What is the role of power and ideology in Media and Communication History?

Media and Communication History investigates how media have been used to legitimise authority, promote nation-building, support or challenge colonial rule, spread consumer culture, and mobilise social movements. It examines propaganda, public relations, news framing, and cultural stereotypes, while also highlighting alternative voices, underground media, and community communication that resist dominant narratives.

How does Media and Communication History connect to Cultural History?

Media and Communication History is closely linked to Cultural History because media are key spaces where meanings are negotiated. It explores how stories, images, and sounds shape collective memories, identities, and everyday practices. By situating media within broader cultural shifts—such as changing ideas of gender, race, class, youth, or nation—it shows how communication helps to organise how societies imagine themselves.

Why is Media and Communication History relevant in a digital age?

Digital media can seem entirely new, but many of today’s issues—misinformation, surveillance, media monopolies, echo chambers, moral panics—have earlier parallels. Media and Communication History provides perspective on these debates by showing how previous generations dealt with disruptive technologies and contested who should control communication, helping students think critically about continuity and change.

What skills do students develop when studying Media and Communication History?

Students learn to interpret diverse kinds of sources, from newspaper articles and broadcasts to adverts and social media campaigns. They practise close reading of images and narratives, contextual analysis, critical thinking about bias and perspective, and clear written and oral communication. They also gain experience in tracing long-term trends and synthesising complex information.

What topics might be covered in a Media and Communication History course?

Topics may include the history of the printing press and the public sphere, the rise of mass newspapers, radio in wartime, cinema and national identity, television and domestic life, advertising and consumer culture, Cold War propaganda, postcolonial media landscapes, the emergence of global news networks, and the historical roots of today’s digital platforms and influencer cultures.

What kinds of careers can Media and Communication History support?

Media and Communication History builds strong foundations for careers in journalism, broadcasting, publishing, cultural and heritage sectors, digital content creation, communications and public relations, policy analysis, NGOs, and education. Employers value graduates who can understand media narratives, assess sources critically, and communicate clearly with different audiences.

Review Questions and Answers:

1. What is media and communication history, and why is it important?

Answer: Media and communication history is the study of how various forms of communication—from oral traditions and print media to digital platforms—have developed and influenced society over time. It is important because it helps us understand the evolution of public discourse, cultural narratives, and power structures. This field provides insight into how information dissemination has shaped political, economic, and social realities. By examining past communication practices, we can better appreciate the impact of media on contemporary culture and society.

2. How did the invention of the printing press transform communication in history?

Answer: The invention of the printing press revolutionized communication by making the mass production of texts possible and vastly increasing the dissemination of knowledge. It broke the monopoly of handwritten manuscripts, which had limited circulation and accessibility, leading to a surge in literacy and education. This transformation helped spread new ideas, fostered scientific and cultural advancements, and contributed to significant societal changes. The printing press laid the foundation for modern mass communication and played a critical role in shaping the intellectual landscape of Europe and beyond.

3. What are the key milestones in the evolution of media from print to digital formats?

Answer: Key milestones in the evolution of media include the advent of the printing press in the 15th century, the development of mass newspapers and periodicals in the 18th and 19th centuries, the rise of radio and television in the 20th century, and the emergence of the Internet and digital media in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Each of these milestones represents a significant leap in how information is produced, disseminated, and consumed by society. They have collectively transformed public communication, enabling rapid exchange of ideas and fostering globalization. Understanding these milestones helps contextualize current digital trends and anticipate future developments in media.

4. How has digital technology changed the way we communicate and share information?

Answer: Digital technology has radically changed communication by enabling instantaneous sharing of information across global networks. The advent of the Internet, social media, and mobile devices has made communication faster, more interactive, and accessible to a broader audience. This digital revolution has also transformed traditional media industries, leading to new forms of content creation, distribution, and consumption. As a result, the landscape of public discourse has become more dynamic and decentralized, influencing both personal interactions and societal structures.

5. What role does media play in shaping public opinion and cultural values?

Answer: Media plays a pivotal role in shaping public opinion and cultural values by acting as the primary source of information and a platform for public discourse. Through various forms—such as news broadcasts, social media, films, and literature—media disseminates ideas and narratives that influence how individuals perceive and interact with the world. It can both reflect and mold societal norms, sometimes reinforcing existing power structures or challenging them through alternative perspectives. The study of media history helps us understand these processes and their implications for democracy, social justice, and cultural transformation.

6. How do historians use primary sources to study media and communication history?

Answer: Historians use primary sources such as newspapers, magazines, broadcast recordings, personal letters, and digital archives to study media and communication history. These sources provide firsthand accounts and direct evidence of past communication practices and public reactions. By analyzing these materials, historians can reconstruct the evolution of media technologies, understand cultural trends, and assess the impact of communication on society. This approach enables a detailed and nuanced understanding of how media has shaped historical events and influenced public discourse.

7. What impact did mass media have on societal transformation during the 20th century?

Answer: Mass media had a profound impact on societal transformation during the 20th century by rapidly disseminating information and shaping public perceptions on a large scale. The widespread adoption of radio, television, and later the Internet revolutionized how people received news, entertainment, and educational content. This mass dissemination of information played a critical role in political mobilization, social change, and cultural shifts, influencing public opinion during significant events such as wars, civil rights movements, and political revolutions. The power of mass media to shape societal narratives remains a central focus in the study of media history.

8. How can the study of media history help us understand the relationship between technology and culture?

Answer: The study of media history helps us understand the relationship between technology and culture by tracing how technological innovations have influenced cultural expression and societal norms. It examines the interplay between technological advancements, such as the printing press, television, and digital media, and the ways in which these innovations have transformed cultural production, dissemination, and consumption. This analysis reveals how shifts in technology can drive changes in cultural practices and social organization, influencing everything from art and literature to political ideologies and everyday communication. By understanding this relationship, we can better appreciate the dynamic and reciprocal influence of technology and culture.

9. What challenges do researchers face when studying the history of media and communication?

Answer: Researchers face several challenges when studying the history of media and communication, including the rapid pace of technological change and the vast volume of digital data available today. The transient nature of digital media, coupled with issues of data preservation and authenticity, complicates the task of documenting historical developments accurately. Additionally, the subjective interpretation of media content and the potential biases in primary sources require researchers to employ critical methodologies and interdisciplinary approaches. Despite these challenges, the study of media history remains essential for understanding the evolution of communication and its impact on society.

10. How does media and communication history contribute to our understanding of cultural globalization?

Answer: Media and communication history contributes to our understanding of cultural globalization by examining how the spread of communication technologies has facilitated the exchange of ideas and cultural practices across borders. It explores how global media networks have influenced the convergence of cultural norms and the creation of transnational cultural identities. This field highlights both the homogenizing effects of global media and the ways in which local cultures adapt and resist these influences. By studying these trends, scholars can gain insights into the mechanisms of cultural globalization and its impact on social, political, and economic structures worldwide.

Thought-Provoking Questions and Answers:

1. How might digital platforms redefine the boundaries of public communication in the 21st century?

Answer:

Digital platforms have the power to redefine the boundaries of public communication by creating spaces where traditional media structures are challenged and new forms of expression emerge. These platforms allow for instantaneous global interaction, enabling individuals from diverse backgrounds to share their ideas and experiences directly, bypassing traditional gatekeepers such as newspapers and television networks. As a result, public discourse becomes more decentralized, dynamic, and inclusive, fostering a more democratic exchange of ideas. This transformation has far-reaching implications for freedom of expression, the formation of public opinion, and the ways in which cultural narratives are constructed and contested.

In addition, digital platforms introduce new challenges, such as the spread of misinformation and the creation of echo chambers, which can distort public communication. Addressing these challenges requires the development of robust digital literacy programs and ethical guidelines to ensure that the benefits of digital communication are maximized while its risks are mitigated. The future of public communication will likely depend on our ability to harness digital technologies in ways that promote transparency, accountability, and inclusive dialogue.

2. In what ways can the integration of augmented reality (AR) enhance the study of media history?

Answer:

The integration of augmented reality (AR) into the study of media history can offer immersive, interactive experiences that bring historical media artifacts and narratives to life. AR can overlay digital information onto physical objects, allowing researchers and students to engage with historical documents, photographs, and artifacts in a more dynamic and contextual manner. This technology enables a deeper understanding of how media was produced, consumed, and interpreted in different historical periods, providing a tangible connection to the past that enhances learning and engagement.

Moreover, AR can facilitate collaborative research by enabling multiple users to explore and interact with digital reconstructions of historical media environments simultaneously. Such interactive experiences can help to visualize the evolution of communication technologies and the cultural contexts in which they operated, fostering a richer understanding of media history. As AR technology continues to advance, it holds the promise of transforming educational practices and making historical research more accessible and engaging to a wider audience.

3. How can cultural studies and media history together help us understand the influence of ideology on public discourse?

Answer:

Cultural studies and media history, when combined, offer a powerful framework for understanding how ideology influences public discourse by critically examining the content and context of media messages. These disciplines analyze how media representations are shaped by the prevailing political, economic, and cultural ideologies of their times, revealing the ways in which power structures are maintained and challenged through public communication. By tracing the evolution of media narratives and their underlying ideological messages, scholars can uncover the processes through which certain ideas become dominant while others are marginalized. This critical perspective not only deepens our understanding of historical media but also provides insights into contemporary debates about media bias and ideological manipulation.

The interdisciplinary nature of this approach encourages the use of diverse methodologies, from textual analysis to ethnographic studies, to explore the intersection of media and ideology. It also highlights the reciprocal relationship between media and society, where public discourse both reflects and shapes ideological beliefs. Together, cultural studies and media history contribute to a more nuanced understanding of the mechanisms of social control and resistance, informing efforts to promote a more balanced and critical media landscape.

4. What impact does the evolution of communication technology have on the construction of cultural memory?

Answer:

The evolution of communication technology has a profound impact on the construction of cultural memory by altering how historical narratives are recorded, transmitted, and remembered. Advances in digital media and communication platforms enable the rapid dissemination of information, which can both preserve and transform cultural memory. For example, social media and digital archives allow for the collection and sharing of personal and collective memories, making it possible for diverse communities to contribute to the historical record. This democratization of memory challenges traditional, often centralized, accounts of history and fosters a more inclusive narrative that reflects the multiplicity of human experience.

However, this transformation also poses challenges, as the ephemeral nature of digital content can lead to issues of preservation and authenticity. The constant flow of information may result in fragmented or distorted memories that complicate efforts to construct a coherent historical narrative. As such, understanding the impact of communication technology on cultural memory requires a critical analysis of both the benefits and limitations of digital media. This inquiry not only enhances our understanding of how memory is constructed but also informs strategies for preserving cultural heritage in the digital age.

5. How might the increasing influence of global media networks affect local cultural identities?

Answer:

The increasing influence of global media networks affects local cultural identities by both homogenizing and diversifying cultural expressions. On one hand, the widespread dissemination of global media content can lead to the erosion of distinct local traditions and the adoption of a more uniform, global culture. This homogenization may dilute unique cultural practices and values, as local audiences are increasingly exposed to dominant global narratives. On the other hand, global media networks also provide a platform for cultural exchange and the celebration of diversity, allowing local cultures to reach broader audiences and engage in cross-cultural dialogue. This dynamic interaction can lead to the creation of hybrid cultural forms that blend traditional and contemporary influences, thereby enriching local identity while also challenging established norms.

Moreover, the impact of global media on local identities is complex and multifaceted, as it can both empower and marginalize communities. Local cultures may adapt to global influences by reinterpreting traditional practices in new and innovative ways, while also asserting their uniqueness in response to homogenizing pressures. The study of these phenomena is crucial for understanding the ongoing negotiation between global and local forces in the construction of cultural identity, and for developing strategies to preserve and promote cultural diversity in an interconnected world.

6. In what ways can public policy benefit from the insights of media and communication history?

Answer:

Public policy can benefit from the insights of media and communication history by drawing on historical lessons to inform contemporary strategies for regulating media, ensuring freedom of expression, and promoting civic engagement. Historical analysis reveals how media has been used to shape public opinion, influence political outcomes, and drive social change, offering valuable lessons on the dynamics of communication and power. Policymakers can use these insights to develop regulations that balance the need for free speech with the protection of public interests, ensuring that media remains a tool for informed and democratic discourse. This historical perspective also highlights the importance of adapting policies to new technological realities and communication trends, fostering a more resilient and responsive regulatory framework.

Additionally, understanding the evolution of media provides a context for addressing contemporary challenges such as misinformation, media concentration, and digital privacy. By learning from past experiences, policymakers can anticipate potential pitfalls and design proactive measures to support a diverse and pluralistic media landscape. The integration of historical insights into public policy ultimately leads to more effective governance and a more informed and engaged citizenry.

7. How can art and visual culture serve as a medium for communicating historical ideas and cultural shifts?

Answer:

Art and visual culture serve as potent mediums for communicating historical ideas and cultural shifts by encapsulating the emotions, values, and ideologies of a particular era in tangible forms. Through paintings, sculptures, photography, and digital art, creators express complex narratives and commentaries that reflect the social, political, and cultural transformations of their time. These visual expressions can convey subtle messages and evoke strong emotional responses, making them powerful tools for preserving and transmitting historical memory. Art often functions as a visual archive, capturing the essence of cultural moments and providing future generations with insights into past experiences and worldviews.

Furthermore, the study of art and visual culture allows historians and cultural scholars to analyze the aesthetic and symbolic dimensions of historical events. This interdisciplinary approach bridges the gap between abstract intellectual concepts and tangible cultural artifacts, enriching our understanding of how cultural shifts occur and how they are experienced by society. By interpreting visual culture within its historical context, scholars can reveal the interplay between creativity, identity, and power, offering a multifaceted perspective on the evolution of human thought and expression.

8. What role does language play in the formation and transmission of cultural history?

Answer:

Language plays a fundamental role in the formation and transmission of cultural history by serving as the primary vehicle through which ideas, values, and historical narratives are communicated and preserved. Through spoken and written language, societies pass down knowledge, traditions, and collective memories from one generation to the next, shaping cultural identity and social cohesion. The nuances of language, including its metaphors, idioms, and rhetorical devices, enrich the interpretation of historical texts and artifacts, revealing deeper layers of meaning and context. As a result, language is not only a tool for communication but also a critical element in the construction and perpetuation of cultural heritage.

Moreover, linguistic analysis allows historians to trace the evolution of cultural concepts and examine how shifts in language reflect broader social and intellectual changes. By studying the transformation of language over time, scholars can gain insights into the dynamics of cultural diffusion and the interplay between tradition and innovation. This understanding of language as both a carrier and a shaper of cultural history is essential for constructing a comprehensive narrative of human development.

9. How might emerging trends in virtual communication alter the historical narrative of media evolution?

Answer:

Emerging trends in virtual communication, such as social media, online forums, and digital broadcasting, are poised to alter the historical narrative of media evolution by introducing new dimensions to how information is shared and consumed. These virtual platforms have redefined the concept of audience and interactivity, enabling real-time global dialogue that was unimaginable in earlier eras. The shift toward digital communication has transformed the dynamics of content creation, distribution, and reception, challenging traditional media hierarchies and fostering more participatory forms of public discourse. As historians examine these trends, they will need to consider how the digital age has reshaped the mechanisms of communication and the cultural implications of these changes.

Additionally, the integration of virtual communication technologies in daily life offers a rich area for research into how digital media influences collective memory and cultural identity. This evolution not only impacts the present but also provides a new context for interpreting the past, as future historians will analyze how digital platforms contributed to shaping modern society. The emerging trends in virtual communication thus compel a re-examination of historical narratives, highlighting the transformative impact of technology on media and culture.

10. How can the study of media and communication history inform our understanding of democracy and civic engagement?

Answer:

The study of media and communication history informs our understanding of democracy and civic engagement by revealing how the dissemination of information and the evolution of communication technologies have shaped public discourse and political participation. Historical analyses show that the rise of mass media, from newspapers to television and the Internet, has played a crucial role in creating informed citizenries and enabling democratic debate. These developments have empowered individuals to participate in civic life, influence public policy, and hold power to account. By examining the interplay between media and democratic processes, scholars can identify the factors that contribute to a vibrant public sphere and understand the challenges posed by media consolidation and misinformation.

Moreover, insights from media history highlight the importance of access to diverse sources of information and the role of free expression in sustaining democratic societies. They also underscore the need for policies that ensure media pluralism and support public engagement in the digital age. This understanding not only enriches academic debates but also guides practical efforts to strengthen democratic institutions and promote civic participation in contemporary society.

11. How might the evolution of visual communication methods affect cultural memory and historical interpretation?

Answer:

The evolution of visual communication methods, such as photography, film, and digital media, has a profound impact on cultural memory and historical interpretation by creating new ways to document and disseminate visual narratives. These methods capture fleeting moments and complex cultural expressions in a format that is both accessible and enduring, allowing for the preservation of historical events and societal trends in a visual context. As visual media becomes increasingly dominant, it shapes how collective memory is constructed, influencing public perceptions of history through powerful imagery and multimedia storytelling. This evolution challenges traditional textual histories and enriches our understanding of the past by incorporating visual dimensions that reflect the emotional and experiential aspects of historical life.

Furthermore, the advent of digital technologies has democratized the creation and distribution of visual content, enabling broader participation in the construction of cultural memory. With social media and online platforms, individuals can contribute to and challenge established historical narratives, fostering a more inclusive and multifaceted representation of the past. This shift not only transforms historical interpretation but also emphasizes the importance of visual literacy in understanding contemporary cultural dynamics.

12. How can interdisciplinary research between media studies and cultural history deepen our understanding of societal transformations?

Answer:

Interdisciplinary research between media studies and cultural history can deepen our understanding of societal transformations by merging analytical frameworks and methodologies from both fields. Media studies offers insights into the technological, aesthetic, and communicative aspects of media production, while cultural history provides context by examining the broader cultural, social, and political environments in which these media operate. Together, they enable a comprehensive analysis of how shifts in media technologies and practices influence cultural narratives and, in turn, drive social change. This collaboration reveals the intricate relationships between media, culture, and power, highlighting the role of communication in shaping historical and contemporary societal dynamics.

Moreover, interdisciplinary research fosters innovative approaches to interpreting complex phenomena such as digital revolution, globalization, and identity formation. By integrating data-driven analysis from media studies with contextual and qualitative insights from cultural history, scholars can construct richer, more nuanced accounts of societal transformations. This synthesis not only enhances academic inquiry but also informs practical strategies for addressing contemporary challenges, ultimately contributing to a deeper and more holistic understanding of how media influences and reflects the evolution of society.

Last updated: