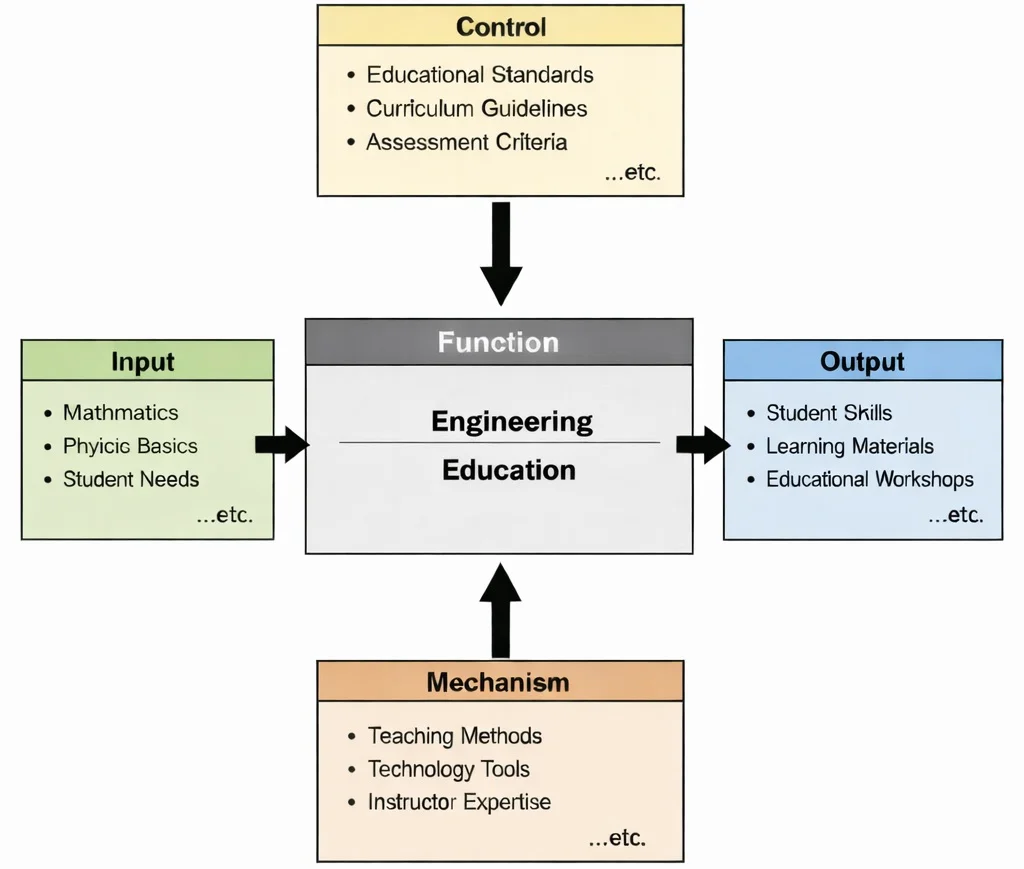

Engineering education, as portrayed in the diagram, is the disciplined transformation of raw foundational knowledge into the ability to design, analyze, and make responsible technical decisions. The inputs—mathematics and physics basics—supply the language of models, while student needs determine how the journey is scaffolded, paced, and contextualized. Controls above the function—standards, curriculum guidance, and assessment criteria—define the destination: what competencies count as “engineering thinking,” what depth is appropriate, and what evidence shows mastery. Mechanisms below—effective teaching methods, technology tools (simulation, computation, lab platforms), and instructor expertise—provide the means to connect theory to real constraints, trade-offs, and safety-minded practice. The outputs therefore go beyond knowledge: students develop durable skills (problem framing, modeling, design reasoning), and educators produce learning materials and workshops that help learners rehearse engineering judgment in increasingly realistic contexts.

Engineering turns science into things that work. It blends physics, chemistry, biology, math and computing to design structures, machines, devices, processes and systems that improve daily life. Below are the core branches you can explore on Prep4Uni, each with a quick description and two starter topics to dive into.

- Civil Engineering — plan, design and maintain the built environment: bridges, buildings, transport and water systems.

Start with: Earthquake & Disaster Engineering, Structural Engineering.

- Mechanical Engineering — model motion, forces and energy to create engines, mechanisms and products.

Start with: Thermodynamics & Heat Transfer, Mechanical Design & CAD.

- Electrical & Electronic Engineering — power, circuits, sensing and communication that make modern tech possible.

Start with: Communication Engineering, Signal Processing.

- Chemical Engineering — turn raw materials into useful products through reactions, separation and scale-up.

Start with: Chemical Process Engineering, Polymer & Plastics Engineering.

- Aerospace & Aeronautical Engineering — aircraft, spacecraft and high-speed flight.

Start with: Aerodynamics, Satellite Technology.

- Environmental Engineering — protect health and ecosystems with cleaner water, air, energy and materials.

Start with: Waste Management Engineering, Green Building & Sustainable Design.

- Biomedical Engineering — apply engineering to medicine: devices, imaging, biomaterials and analytics.

Start with: Biomechanics, Biomaterials.

- Industrial & Manufacturing Technologies — design how things are made: processes, quality, automation and scale.

Start with: Smart Manufacturing & Industry 4.0, Industrial Automation & Robotics.

Table of Contents

Engineering: Designing, Building, and Maintaining Systems

Engineering is the discipline of making useful things behave reliably in the real world. It takes ideas—often born from science, mathematics, and human needs—and turns them into systems that can be designed, built, operated, repaired, and trusted. A bridge, a water network, a phone, a medical device, a solar farm, a factory line, even a search engine: each is a system with parts that must work together under time, cost, safety, and environmental constraints.

A practical way to understand engineering is to view it as a loop with three repeating responsibilities. First, design: define requirements, predict performance, choose materials and architectures, and plan for uncertainty. Second, build: translate drawings and models into physical or digital reality, where tolerances, workmanship, supply chains, and testing decide whether the idea survives contact with the world. Third, maintain: keep the system safe and useful over time through inspection, monitoring, upgrades, and learning from failures. This maintenance mindset is what separates a clever prototype from an engineering solution that society can depend on.

In many fields, the “best” engineering answer is not the most elegant theory but the most dependable trade-off. Engineers learn to weigh competing goals—strength vs. weight, speed vs. accuracy, cost vs. durability, efficiency vs. complexity—and to make these choices visible and defensible through calculations, simulations, tests, and clear documentation. In short: engineering is not just invention; it is responsible implementation.

Engineering Thinking versus Scientific Thinking

Engineering and science are closely related, but they ask different questions and reward different kinds of thinking. Science is primarily concerned with understanding how the world works—discovering laws, patterns, and explanations that are universally valid. Engineering, by contrast, is concerned with making things work well enough, safely enough, and affordably enough in specific real-world contexts.

A scientist might ask why a material behaves a certain way under stress; an engineer asks whether that material is suitable for a bridge, an aircraft, or a medical implant, given cost, manufacturing limits, safety margins, and long-term reliability. Scientific answers tend to be open-ended and refined over time, while engineering answers must often be decisive, documented, and implemented under deadlines.

This difference shapes how problems are approached. Scientific thinking values controlled experiments, idealized models, and isolating variables. Engineering thinking accepts complexity, uncertainty, and imperfect information, using approximations, safety factors, simulations, and testing to reduce risk rather than eliminate it entirely.

Understanding this distinction early helps students adjust expectations. Engineering study is not just about learning formulas or theories, but about learning judgment: when a model is good enough, when assumptions break down, and when human, ethical, or environmental considerations override purely technical optimization.

What Engineers Are Ultimately Responsible For

Engineering is not only a technical profession but also a social responsibility. Engineers make decisions that affect public safety, environmental sustainability, economic efficiency, and long-term societal well-being. Unlike purely academic work, engineering outcomes are deployed in the real world, where failures can have serious human, financial, and ecological consequences.

At the core of engineering responsibility is safety. Engineers are expected to design systems that operate reliably under expected conditions and fail predictably under extreme ones. This includes accounting for material limits, human error, environmental stresses, and unexpected interactions between components. Safety factors, redundancy, and rigorous testing are not optional—they are ethical obligations.

Accountability distinguishes engineering from many other disciplines. When a bridge collapses, a medical device malfunctions, or a power system fails, engineers are called upon to explain design choices, calculations, assumptions, and trade-offs. Documentation, standards compliance, and professional codes of conduct exist precisely because engineering decisions must be defensible long after they are made.

Ethical responsibility extends beyond preventing failure. Engineers must consider who benefits from a system, who bears its risks, and how its deployment affects communities and the environment. Decisions about cost-cutting, material sourcing, automation, and energy efficiency often involve ethical judgment as much as technical optimization.

Modern engineering practice increasingly emphasizes sustainability and social impact. Engineers are expected to minimize environmental harm, reduce waste, and design systems that can adapt to future needs rather than becoming short-lived liabilities. Lifecycle thinking—considering construction, operation, maintenance, and end-of-life disposal—is now a core professional responsibility.

For students, understanding these responsibilities early helps frame engineering education correctly. University training is not only about mastering equations or software tools, but about developing professional judgment, ethical awareness, and a sense of duty toward society. These qualities ultimately define what it means to be an engineer.

Failure as a Design Teacher in Engineering

Engineering advances not only through success, but through careful study of failure. Accidents, near-misses, and system breakdowns have historically played a central role in shaping safer designs, improved standards, and more resilient technologies. In engineering, failure is not simply an outcome to be avoided—it is a powerful source of knowledge when analyzed responsibly.

Many engineering disciplines rely on post-incident investigations to understand why systems behaved unexpectedly. Structural collapses, aviation incidents, industrial accidents, and software outages are examined in detail to identify root causes, contributing factors, and systemic weaknesses. These investigations often reveal that failures rarely stem from a single mistake, but from chains of technical, human, and organizational factors.

Near-misses are especially valuable learning opportunities. When a system narrowly avoids failure, engineers can study stress limits, design margins, and human interactions without the severe consequences of an actual disaster. Industries such as aviation, nuclear engineering, and chemical processing actively document near-miss events to strengthen future designs and operating procedures.

Engineering standards and codes frequently evolve in response to failure analysis. Load factors, safety margins, inspection requirements, and testing protocols are often revised after real-world incidents expose hidden vulnerabilities. Over time, this process transforms hard-earned lessons into formalized knowledge that benefits the entire profession.

Failure analysis also shapes engineering education. Case studies of historical failures—such as bridge collapses, spacecraft accidents, or infrastructure breakdowns—are widely used to teach students how design assumptions, communication gaps, and risk underestimation can lead to serious consequences. These examples cultivate engineering judgment, humility, and respect for uncertainty.

Importantly, modern engineering culture emphasizes learning rather than blame. While accountability remains essential, effective engineering organizations focus on transparent reporting, systematic analysis, and continuous improvement. This approach encourages engineers to surface problems early, refine designs iteratively, and prevent small issues from escalating into catastrophic failures.

In this sense, failure acts as a design teacher. Each analyzed incident strengthens future systems, informs better decision-making, and reinforces the responsibility engineers carry when transforming ideas into real-world technologies that people depend on every day.

Engineering Judgment: When Equations Are Not Enough

Equations, models, and simulations are essential tools in engineering, but they are not sufficient on their own. Real systems operate under uncertainty: materials vary, users behave unpredictably, environments change, and assumptions made during analysis rarely hold perfectly in practice. Engineering judgment is the ability to recognize the limits of formal calculations and to make sound decisions when information is incomplete or ambiguous.

Engineering judgment develops through experience, reflection, and exposure to real-world constraints. It involves knowing which model is appropriate, when simplifying assumptions are acceptable, and when added complexity creates false confidence rather than better understanding. A skilled engineer understands that a precise answer to the wrong question is less valuable than a reasonable answer to the right one.

Judgment also plays a critical role in risk assessment. Engineers must decide how conservative a design should be, where to add redundancy, and which failure modes deserve the most attention. These decisions are rarely dictated by formulas alone; they require contextual awareness, awareness of consequences, and an understanding of how systems behave over time.

In professional practice, engineering judgment is what allows engineers to communicate uncertainty honestly, defend design choices clearly, and adapt when conditions change. It transforms technical knowledge into responsible action, and it is one of the defining qualities that distinguishes a trained engineer from someone who merely applies calculations mechanically.

Trade-offs, Constraints, and Imperfect Solutions

Engineering problems rarely have perfect solutions. Instead, they involve navigating trade-offs among competing objectives under real constraints. A design that maximizes performance may increase cost; a design that minimizes weight may reduce durability; a design that improves safety may require additional complexity or maintenance. Engineering is the discipline of making these compromises explicit and manageable.

Constraints shape every engineering decision. These may include physical limits, regulatory requirements, budgets, timelines, environmental conditions, manufacturing capabilities, and human factors. Rather than viewing constraints as obstacles, engineers treat them as defining features of the problem space. A successful design is one that works well within its constraints, not one that ignores them.

Trade-offs are evaluated using analysis, testing, and comparison, but they are ultimately resolved through informed choice. Engineers must prioritize which goals matter most in a given context and justify why certain compromises are acceptable. This process requires transparency, documentation, and a clear understanding of stakeholder needs.

Accepting imperfection is central to engineering thinking. Systems are designed not to be flawless, but to be robust, repairable, and resilient. By anticipating limitations and planning for degradation, failure, and adaptation, engineers create solutions that remain useful over time. In this way, engineering progress is driven not by ideal answers, but by practical solutions that work reliably in the real world.

Engineering as a Team-Based Discipline

Modern engineering is rarely the work of a single individual. Most engineering systems are too complex, too large, and too consequential to be designed or maintained by one person alone. As a result, engineering is fundamentally a team-based discipline, where success depends on coordination, communication, and shared responsibility across diverse roles and expertise.

Engineering teams often bring together specialists from different domains: design engineers, analysts, software developers, materials experts, manufacturing engineers, safety reviewers, and project managers. Each contributes a partial view of the system, and effective engineering requires integrating these perspectives into a coherent whole. Miscommunication between team members is a common source of engineering failure, which is why documentation, design reviews, and clear interfaces are treated as technical necessities rather than administrative overhead.

Team-based engineering also involves collaboration beyond the engineering profession itself. Engineers regularly work with clients, regulators, operators, technicians, and end users. Understanding how non-engineers interact with systems is essential for designing solutions that are usable, maintainable, and safe in practice.

For students, this means that engineering education is not only about individual problem-solving skill. It also involves learning how to explain technical ideas clearly, evaluate others’ designs constructively, accept critique, and make collective decisions under uncertainty. These collaborative skills are central to professional engineering practice and are developed deliberately through group projects and design work.

Standards, Codes, and Why Engineers Don’t Start from Scratch

Engineering does not begin with a blank page. Most engineering work builds upon established standards, codes, and best practices that reflect decades of accumulated experience. These documents capture lessons learned from past successes and failures, translating them into requirements for materials, dimensions, safety margins, testing procedures, and documentation.

Standards serve several purposes. They promote safety by setting minimum acceptable performance levels, enable compatibility between systems and components, and reduce uncertainty in design and manufacturing. Codes and standards also provide a common technical language that allows engineers from different organizations and countries to work together effectively.

Following standards does not eliminate creativity; instead, it channels it. Engineers innovate within constraints, adapting established frameworks to new contexts, technologies, and requirements. When standards are insufficient or outdated, engineers may justify deviations through additional analysis, testing, or certification—but such departures must be carefully documented and defensible.

Learning to work with standards is a key part of becoming an engineer. Students are gradually introduced to industry codes, safety regulations, and professional guidelines so they understand that responsible engineering involves more than technical correctness. It also involves compliance, traceability, and respect for shared professional knowledge that protects both users and engineers themselves.

Engineering Communication: Explaining Decisions to Non-Engineers

Engineering decisions rarely affect engineers alone. Designs influence clients, regulators, operators, investors, policymakers, and the public—many of whom do not share the same technical background. Effective engineering communication is therefore not about simplifying ideas until they lose meaning, but about translating complex reasoning into explanations that are accurate, transparent, and relevant to the audience.

Engineers must often explain why a particular option was chosen, what assumptions were made, what risks remain, and what trade-offs were accepted. This requires moving beyond equations and diagrams to narratives that connect technical choices to safety, cost, reliability, timelines, and societal impact. Poor communication can undermine trust even when the technical work is sound.

Different audiences require different forms of explanation. A regulator may focus on compliance and risk, a manager on cost and schedule, an operator on usability and maintenance, and the public on safety and environmental impact. Skilled engineers learn to adapt their language without distorting the underlying facts, making uncertainty visible rather than hiding it behind technical jargon.

In professional practice, communication is inseparable from responsibility. Clear documentation, concise reports, design reviews, and honest discussions of limitations ensure that decisions can be understood, questioned, and improved. For students, learning to communicate engineering reasoning is as important as learning to perform calculations, because engineering only fulfills its purpose when others can understand and act on it.

Why Engineering Solutions Must Be Defensible Years Later

Engineering work does not end when a system is built or deployed. Bridges, buildings, medical devices, software systems, and energy infrastructure may remain in use for decades, long after the original designers have moved on. For this reason, engineering solutions must be defensible not only at the moment of approval, but years later when conditions, standards, or expectations have changed.

Defensibility means that design choices can be explained and justified based on the information, standards, and constraints that existed at the time. Engineers are expected to document assumptions, calculations, testing results, and trade-offs so that others can understand why decisions were made. This documentation becomes critical during audits, failure investigations, upgrades, or legal review.

As technologies evolve, earlier designs may appear inefficient or conservative by modern standards. However, responsible engineering is judged by whether decisions were reasonable and ethical given the knowledge available at the time, not by hindsight alone. Clear records protect both the public and the engineers by showing that risks were considered and managed thoughtfully.

For students, this long-term perspective reframes engineering education. Assignments and projects are not merely exercises to obtain correct answers; they are practice in making decisions that could, in principle, be examined years later. Learning to justify choices, acknowledge uncertainty, and leave a clear trail of reasoning is a core professional habit that distinguishes engineering from short-lived problem solving.

How Engineering Is Studied at University

University engineering is usually a sequence of foundations followed by specialization and practice. Early years focus on mathematics, physics, programming, and core engineering principles such as statics, dynamics, circuits, materials, thermodynamics, and basic modeling. As courses advance, students learn how to move from assumptions to designs: drawing and CAD, simulation and computation, laboratory measurement, prototyping, and testing. Team projects become increasingly important because real engineering is rarely a solo sport; communication, documentation, and project planning are treated as technical skills, not “soft” extras. By the final year, capstone work often looks like a small version of industry: define requirements, propose a design, justify choices, manage trade-offs, validate performance, and explain the result to others in a way that survives criticism.

Fields of Engineering and Their Expansions

Civil Engineering

Civil engineering focuses on the design, construction, and maintenance of infrastructure projects such as buildings, bridges, roads, and water systems.

- Key Applications:

- Construction of skyscrapers, tunnels, and dams.

- Development of sustainable urban infrastructure.

- Disaster-resilient structures to mitigate natural calamities.

- Water resource management, including reservoirs and irrigation systems.

- Current Developments:

- Smart cities integrating IoT for better infrastructure management.

- Use of green construction materials for sustainability.

- Advanced modeling tools like Building Information Modeling (BIM).

Mechanical Engineering

Mechanical engineering deals with the design, analysis, and manufacturing of mechanical systems and devices.

- Key Applications:

- Automotive engineering, including electric vehicles (EVs).

- Robotics and automation in manufacturing and healthcare.

- Design of turbines, engines, and HVAC systems.

- Renewable energy systems, such as wind and hydroelectric power.

- Current Developments:

- Additive manufacturing (3D printing) for complex parts.

- Integration of AI in mechanical system diagnostics.

- Advanced materials for lighter and more efficient machines.

Electrical and Electronic Engineering

This field focuses on the development and application of electrical and electronic systems, ranging from power generation to communication technologies.

- Key Applications:

- Power grids, renewable energy systems, and battery storage solutions.

- Consumer electronics, including smartphones and wearables.

- Communication networks, including 5G and IoT.

- Automation systems and smart devices.

- Current Developments:

- Quantum electronics and advancements in semiconductors.

- AI-driven control systems for smarter energy distribution.

- Development of efficient electric-vehicle charging networks.

Chemical Engineering

Chemical engineering involves the use of chemical processes to create materials, fuels, and other products essential for modern life.

- Key Applications:

- Production of chemicals, plastics, and pharmaceuticals.

- Development of sustainable fuels and green chemistry.

- Water treatment and desalination technologies.

- Food and beverage production.

- Current Developments:

- Carbon capture and utilization technologies.

- Innovations in biodegradable materials.

- Advanced process optimization using AI and machine learning.

Aerospace and Aeronautical Engineering

This field focuses on the design, development, and maintenance of aircraft, spacecraft, and related technologies.

- Key Applications:

- Design of commercial and military aircraft.

- Space exploration technologies, including satellites and rockets.

- Drone development for logistics, surveillance, and agriculture.

- Advanced propulsion systems for interplanetary missions.

- Current Developments:

- Hypersonic travel and next-generation jet engines.

- Lightweight materials for fuel-efficient aircraft.

- Integration of AI in avionics and navigation systems.

Environmental Engineering

Environmental engineering aims to solve environmental challenges through innovative technologies and sustainable practices.

- Key Applications:

- Wastewater treatment and solid-waste management.

- Air-quality monitoring and pollution control systems.

- Renewable energy systems and energy-efficient designs.

- Restoration of natural ecosystems.

- Current Developments:

- Climate-change mitigation technologies.

- Use of AI and sensors for environmental monitoring.

- Sustainable construction practices and green certifications.

Biomedical Engineering

Biomedical engineering merges engineering principles with biological sciences to create healthcare technologies.

- Key Applications:

- Development of prosthetics, implants, and medical devices.

- Biomechanical systems, such as artificial organs.

- Medical imaging technologies, including MRI and CT scanners.

- Rehabilitation engineering and assistive technologies.

- Current Developments:

- Wearable health-monitoring devices.

- Innovations in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine.

- AI-driven diagnostic tools and personalized treatments.

Industrial and Manufacturing Technologies

This field focuses on optimizing manufacturing processes and systems for improved efficiency and productivity.

- Key Applications:

- Automation and robotics in assembly lines.

- Quality control systems and predictive maintenance.

- Lean manufacturing and Six Sigma practices.

- Supply-chain optimization and logistics.

- Current Developments:

- Industry 4.0 integrating IoT and smart sensors.

- Advanced manufacturing techniques like additive manufacturing.

- Energy-efficient and sustainable production processes.

Prerequisites & quick math toolbox

- Maths you’ll actually use: ratios & units, functions, vectors, basic calculus, probability & statistics. See: Mathematics hub.

- Science refresh: mechanics (forces, energy, momentum), electricity & magnetism, materials basics. See: Science hub.

- Digital skills: version control (Git), spreadsheets & plotting, a little Python for data and automation. See: IT hub.

- Safety first: lab PPE, machine guarding, electrical safety, risk assessment.

Cross-Field Synergies

Engineering increasingly relies on collaboration across disciplines to address complex global challenges. These synergies blend engineering specializations with environmental science, biology, and chemistry to create technologies that are not only innovative but also socially and ecologically responsible.

- Civil Engineering + Environmental Engineering:

Green building technologies and sustainable infrastructure design—stormwater recycling, permeable pavements, vegetated roofs—embed environmental principles into structural design. Frameworks from ASCE and policies aligned with the UN SDGs support this integration.

- Mechanical Engineering + Biomedical Engineering:

Prosthetics, robotic surgery, wearable health devices, exoskeletons, and MEMS arise from combining dynamics/materials expertise with anatomical and clinical insight. See programs funded by NIBIB for examples.

- Chemical Engineering + Renewable Energy:

Perovskite solar coatings, solid-state batteries, and hydrogen production leverage advanced materials and catalysis. Work from NREL highlights scalable green-energy processes.

- Electrical Engineering + AI:

Smart grids, autonomous systems, and predictive diagnostics fuse circuit design with machine learning. IEEE Spectrum regularly covers these advances.

- Materials Science + Aerospace Engineering:

Composites and thermal-protection systems enable hypersonics, reusable launch vehicles, and deep-space missions. NASA’s STMD funds key materials and propulsion research.

Challenges and Future Directions of Engineering

Sustainability

Low-carbon design, life-cycle analysis, and circular-economy practices are now core criteria. See circular economy frameworks for guidance.

Integration of AI

From predictive maintenance to real-time optimization, AI powers Industry 4.0, autonomous systems, and automated quality checks. Overview: Industry 4.0.

Resource Management

Optimize materials, energy, and water; ensure ethical sourcing of critical minerals. See the IEA’s report on critical minerals in clean-energy transitions.

Global Collaboration

International alliances (e.g., IEA Clean Energy Technology Collaboration) help scale inclusive, resilient engineering solutions.

Why Study Engineering (Physical Technologies)

Understanding Core Technological Systems

Engineering covers systems involving mechanics, electronics, materials, and energy—foundations for innovation and practical problem-solving.

Applications in Engineering and Industry

Central to manufacturing, transport, energy, and construction—students work with motors, sensors, control circuits, and real-world systems.

Foundation for Advanced Engineering Fields

Builds toward mechatronics, robotics, aerospace, and renewable energy—confidence for tackling complex technical challenges.

Hands-On and Experimental Learning

Laboratories and projects reinforce theory through practice, developing technical proficiency and teamwork.

Driving Technological Innovation

Students learn to design for performance, efficiency, and sustainability—becoming future innovators and problem-solvers.

🎥 Related Video – Why Study Emerging Technologies

Mechanical systems, structures, and energy infrastructure increasingly integrate with digital innovations like AI, sensors, and automation. This video from our Why Study series highlights eight reasons to explore emerging technologies—a powerful complement to engineering disciplines.

Mini-projects you can finish in ≈10 hours

Pick one that matches your lane. Keep a short logbook (goal, plan, tests, results, next steps).

- Civil Engineering: design a small pedestrian footbridge in CAD and verify span/deflection with a simple beam calc. Optional: compare wood vs. steel. Start here: Civil.

- Mechanical Engineering: build a gearbox or linkage in CAD and 3D-print one part; measure torque or motion and compare to your model. Start: Mechanical.

- Electrical & Electronic: make a sensor logger (temp/accelerometer) with a microcontroller; plot data and apply a simple filter. Start: EEE.

- Chemical Engineering: simulate a 2-stage separation (mass balance spreadsheet) and validate with a kitchen-safe demo (e.g., salt/water). Start: Chemical.

- Aerospace: design a simple wing profile; estimate lift/drag with a free airfoil tool, then test a paper or balsa wing with a fan. Start: Aerospace.

- Environmental: prototype a DIY water filter; measure turbidity/flow and report improvements. Start: Environmental.

- Biomedical: analyze gait or grip strength with a phone sensor; discuss biomechanics and measurement error. Start: Biomedical.

- Industrial & Manufacturing: map a process (swimlane diagram), then propose a 5S + one automation step; estimate cycle-time gain. Start: Industrial.

Tools & starter kits

- CAD & simulation: FreeCAD / Onshape (CAD), KiCad (PCB), Octave (MATLAB-like), Python + NumPy/Matplotlib, basic FEA/CFD when available.

- Electronics: Arduino-class MCU, breadboard, sensors (temp, IMU), USB scope or logic probe (optional).

- Making: 3D printer or makerspace access, hand tools, calipers, soldering iron.

- Data & reports: spreadsheet for calculations, version control (Git), a one-page PDF summary with results and next steps.

From subjects to roles

| Branch | Entry-level roles | Grow toward |

|---|---|---|

| Civil | Assistant structural/civil engineer, site engineer, CAD/BIM tech | Structural lead, transport/water specialist, project manager |

| Mechanical | Design engineer, test engineer, HVAC/energy analyst | Systems architect, reliability lead, product owner |

| Electrical & Electronic | Embedded engineer, power systems junior, RF/communications junior | Power planning, SoC/FPGA, automation/controls lead |

| Chemical | Process engineer, quality/validation, EH&S associate | Plant/process optimization, sustainability lead |

| Aerospace | Aerodynamics/structures analyst, avionics integration | Flight systems, mission ops, certification lead |

| Environmental | Water/air analyst, remediation associate, sustainability coordinator | Environmental consultant, ESG program lead |

| Biomedical | Clinical/biomedical engineer, device test engineer | R&D lead, regulatory/quality lead, translational engineer |

| Industrial & Manufacturing | Manufacturing/automation engineer, industrial data analyst | Operations excellence, Industry 4.0 architect |

Frequently Asked Questions

What is engineering?

Engineering is the discipline of designing, building, operating, and maintaining systems that work reliably in the real world. It applies scientific principles, mathematical models, and practical judgment to create solutions that meet functional, safety, economic, and societal requirements.

Which major areas are typically included within engineering?

Engineering includes major areas such as mechanical, civil, electrical and electronic, chemical, computer and software, biomedical, environmental, and industrial engineering. These fields apply mechanics, thermodynamics, electromagnetism, materials science, computation, and systems thinking to real-world problems.

How does materials science influence engineering design?

Materials science provides engineers with metals, polymers, composites, and functional materials whose mechanical, thermal, electrical, and chemical properties determine system performance. Advances in materials enable lighter structures, higher efficiency, improved durability, and new engineering applications across infrastructure, energy, electronics, and healthcare.

What role do sensors and measurement play in engineering systems?

Sensors and measurement systems allow engineers to observe, monitor, and control real-world behavior. By converting physical quantities such as force, temperature, pressure, motion, or chemical concentration into usable signals, they support feedback control, diagnostics, safety monitoring, and long-term system reliability.

How is engineering involved in energy and sustainability?

Engineering plays a central role in energy generation, conversion, storage, and distribution. This includes renewable energy systems such as wind, solar, hydroelectric, and energy storage technologies, as well as efficiency improvements in buildings, transport, and industrial processes through thermal, electrical, and materials engineering.

How does engineering support modern infrastructure and cities?

Engineering supports modern infrastructure through the design and maintenance of transport networks, buildings, power grids, water systems, and communication networks. In smart and resilient cities, engineering integrates physical systems with sensing, control, and data-driven management to improve safety, efficiency, and sustainability.

What challenges arise when engineering designs move from prototypes to real-world deployment?

Moving from prototypes to real-world deployment requires engineers to address manufacturability, cost, safety, reliability, standards compliance, and long-term maintenance. Designs often must be revised to withstand variability in materials, operating conditions, human use, and environmental stress while remaining economically viable.

How do digital tools interact with engineering practice?

Digital tools support engineering by enabling modelling, simulation, data analysis, and system integration. Computational tools allow engineers to explore design options before construction, while connected systems such as industrial IoT enable monitoring, optimisation, and adaptive control of engineered systems throughout their lifecycle.

Engineering — Conclusion

Engineering shapes how we build, move, and sustain life. With continuous advances, it will further enhance global infrastructure, manufacturing, and quality of life—driving a sustainable, innovative future.Engineering – Review Questions and Model Answers

These questions help you move from recognising examples of physical technologies to analysing how they are designed, scaled, and integrated with digital systems.

1. What are physical technologies and which key areas do they typically cover?

Answer: Physical technologies are engineered systems that apply the laws of physics to act on matter and energy in the real world. They include areas such as advanced materials and structures, sensing and measurement systems, robotics and automation, renewable energy hardware, fluid and thermal systems, and transport and infrastructure technologies. Across these areas, the common theme is turning theoretical principles into tangible devices and systems that deliver useful functions reliably and safely.

2. How do innovations in materials science influence the evolution of physical technologies?

Answer: Materials innovations change what is physically possible for devices and structures. Stronger and lighter alloys allow aircraft, vehicles and turbines to be more efficient; advanced composites enable blades, pressure vessels and sporting equipment with tailored stiffness and damping; functional materials with special electrical, thermal or optical properties open the door to better sensors, batteries and actuators. As new materials become available, engineers can redesign physical technologies to achieve higher performance, longer life and lower energy use.

3. Why are sensors viewed as a critical interface between the physical world and engineered systems?

Answer: Sensors translate physical quantities—such as force, temperature, pressure, vibration or chemical concentration—into signals that control systems and computers can interpret. Without accurate sensing, a system has no reliable picture of its environment or internal state, so it cannot regulate behaviour, detect faults or optimise performance. In modern physical technologies, sensing is tightly integrated with actuation and control, forming feedback loops that keep processes stable and efficient.

4. How are renewable energy technologies reshaping the landscape of physical technologies?

Answer: Renewable energy brings new design priorities: capturing variable natural energy sources, integrating storage, and connecting to smart grids. Wind turbines, solar arrays, hydro and marine systems require specialised structures, power electronics, and control strategies that differ from conventional fossil-fuel plants. This shift drives innovation in blades, generators, inverters and grid interfaces, and it pushes physical technologies to operate efficiently under fluctuating conditions while contributing to decarbonisation goals.

5. What is the significance of robotics within the wider family of physical technologies?

Answer: Robotics combines mechanical structures, actuators, sensors and control algorithms into systems that can act autonomously or semi-autonomously in the physical world. Robots are used for tasks that are repetitive, hazardous or require high precision, from industrial assembly and warehouse logistics to surgery and planetary exploration. As robots become more capable and collaborative, they influence how factories are laid out, how services are delivered, and how engineers think about the division of labour between humans and machines.

6. In what ways do physical technologies contribute to the development of smart cities?

Answer: Smart cities rely on physical technologies embedded in infrastructure: instrumented roads and bridges, adaptive traffic lights, energy-efficient buildings with smart HVAC, and distributed environmental monitoring stations. These systems collect data on flows of people, vehicles, energy and water, and they adjust operation in real time. The result can be reduced congestion, lower energy consumption, better air quality and improved public safety—provided the underlying hardware is robust, well maintained and thoughtfully integrated.

7. What challenges arise when scaling physical technologies from laboratory prototypes to industrial deployment?

Answer: Prototypes may work under controlled conditions but encounter new constraints in large-scale production and field use. Challenges include high manufacturing costs, the need for specialised equipment, integration with legacy systems, and variability in real environments. Meeting reliability and safety requirements at scale demands thorough testing, standardisation and certification. Collaboration among researchers, manufacturers and regulators is often needed to refine designs and processes so that promising ideas become economically viable products.

8. How can physical technologies improve the reliability and efficiency of transportation systems?

Answer: In transport, physical technologies influence vehicle structures, propulsion, braking, suspension, and the infrastructure vehicles use. Lightweight materials and aerodynamic design reduce energy consumption; advanced braking and stability systems enhance safety; embedded sensors and communication modules support traffic management and autonomous driving. At the network level, smart signalling, real-time monitoring of rails and roads, and better maintenance strategies all rely on robust physical technologies working together.

9. What are the potential benefits of combining physical technologies with digital innovations such as IoT and cloud computing?

Answer: When physical technologies are connected to digital platforms, systems can be monitored and controlled remotely, data can be analysed at scale, and behaviour can be optimised automatically. Internet of Things devices transmit sensor readings to cloud-based analytics, which can detect patterns, predict failures and suggest adjustments. This fusion leads to smarter factories, hospitals, energy networks and buildings, where physical assets become part of a larger, data-driven system rather than isolated machines.

10. How do simulation and modelling support the development and optimisation of new physical technologies?

Answer: Simulation and modelling allow engineers to explore designs in a virtual environment before building hardware. Using tools based on mechanics, thermodynamics, electromagnetism or multiphysics, they can estimate stresses, temperatures, flows, vibrations or electromagnetic fields under realistic loads. This helps identify weaknesses, compare design options and tune parameters early in the process, reducing the number of physical prototypes required. In turn, this lowers cost, shortens development time and leads to more reliable, better-optimised physical technologies when they are finally built and tested.

Engineering: Thought-Provoking Questions and Answers

How can the integration of IoT devices and physical technologies revolutionize industrial automation?

Answer: The integration of IoT devices with physical technologies is set to revolutionize industrial automation by enabling real-time monitoring, control, and data-driven decision-making. IoT sensors embedded in machinery and infrastructure can continuously collect and transmit data on performance, wear, and environmental conditions. This information allows for predictive maintenance, reducing downtime and optimizing production processes. By leveraging the connectivity and computational power of IoT, industries can achieve unprecedented efficiency and responsiveness in their operations.

Additionally, the seamless integration of IoT with automation systems facilitates dynamic adjustments to operational workflows, enabling facilities to adapt to changing conditions swiftly. This convergence not only boosts productivity but also enhances the safety and sustainability of industrial environments, ultimately transforming the way industries function in a digital age.What ethical issues might arise from the widespread implementation of physical technologies in public spaces, and how can they be addressed?

Answer: Widespread implementation of physical technologies in public spaces raises ethical issues related to privacy, surveillance, and data security. As smart sensors and monitoring devices become ubiquitous, there is a risk of invasive data collection that could infringe on individual privacy rights. Additionally, the potential for misuse or unauthorized access to collected data poses significant security concerns. Addressing these issues requires the development of robust regulatory frameworks and transparent data policies that protect citizens while enabling technological advancement.

Furthermore, public engagement and informed consent are essential to ensure that communities are aware of and comfortable with the technologies being deployed. Implementing strict access controls, data anonymization techniques, and regular audits can help mitigate these risks. By balancing technological innovation with ethical considerations, policymakers can foster an environment that respects individual rights and promotes trust in public systems.How might advancements in energy-efficient technologies impact the sustainability of urban infrastructure?

Answer: Advancements in energy-efficient technologies have the potential to significantly enhance the sustainability of urban infrastructure by reducing energy consumption and lowering carbon emissions. Innovations such as smart grids, energy-efficient building materials, and advanced HVAC systems enable cities to optimize their energy usage and improve overall operational efficiency. These technologies help mitigate the environmental impact of urban development while also reducing costs associated with energy consumption. They play a critical role in the transition towards greener and more sustainable cities by promoting renewable energy sources and smart energy management systems.

Additionally, the integration of energy-efficient technologies with real-time monitoring and control systems allows urban planners to adjust and optimize infrastructure performance dynamically. This adaptive approach not only improves resilience against energy fluctuations but also supports long-term sustainability goals. As cities continue to grow, these advancements will be essential for building environmentally responsible and economically viable urban environments.What role does simulation play in bridging the gap between theoretical research and practical application in physical technologies?

Answer: Simulation is a crucial tool that bridges the gap between theoretical research and practical application by providing a virtual environment in which complex systems can be modeled and tested. It allows researchers and engineers to experiment with designs, predict system behavior, and identify potential issues before implementing physical prototypes. This process not only accelerates the development cycle but also reduces costs and risks associated with real-world testing. Simulations can replicate a wide range of scenarios, ensuring that the final product is robust and optimized for actual operating conditions.

Moreover, simulation enhances collaboration across disciplines by enabling stakeholders to visualize and discuss potential solutions in a controlled, interactive setting. It facilitates iterative design improvements and offers valuable insights that inform both theoretical advancements and practical innovations. This dynamic interaction between simulation and application is fundamental to the successful development and deployment of cutting-edge physical technologies.How might advancements in sensor technology improve the accuracy of data collection in challenging environments?

Answer: Advancements in sensor technology are crucial for improving the accuracy of data collection in challenging environments such as extreme temperatures, high pressures, or remote locations. Modern sensors are designed with enhanced sensitivity, durability, and precision, allowing them to capture reliable data under conditions that would previously compromise measurement quality. These improvements lead to better-informed decisions, more efficient systems, and increased safety in industrial, environmental, and scientific applications. Enhanced sensors also support real-time monitoring and adaptive control, ensuring that systems can respond quickly to changing conditions.

Additionally, the integration of sensor networks with advanced data processing and machine learning algorithms can further refine the accuracy of the collected data. By filtering noise and compensating for environmental variables, these technologies ensure that the data reflects the true state of the system, thereby enabling more accurate modeling and analysis. This is particularly important for critical applications such as climate monitoring and industrial automation.How can robust statistical methods improve the analysis of complex data in physical technologies?

Answer: Robust statistical methods enhance the analysis of complex data by providing techniques that are less sensitive to outliers, skewed distributions, and non-standard data conditions. These methods help ensure that the results are reliable even when the data deviates from ideal assumptions. In physical technologies, where data can be noisy or incomplete, robust methods allow for accurate estimation of key parameters and error margins. Techniques such as robust regression, bootstrapping, and non-parametric tests help analyze data more effectively and support better decision-making in design and control.

Furthermore, the use of these methods can improve the overall quality of data analysis by highlighting underlying patterns that might be obscured by anomalies. This leads to more accurate models and predictions, which are essential for optimizing the performance and safety of physical systems. Robust statistical techniques are therefore indispensable for managing the complexity inherent in real-world data.What challenges do engineers face when integrating physical technologies with digital systems, and how can they be overcome?

Answer: Integrating physical technologies with digital systems presents challenges such as interoperability, data synchronization, and the need for reliable communication protocols. Engineers must ensure that diverse components—from sensors and actuators to processing units—work seamlessly together to achieve accurate and timely data exchange. Overcoming these challenges requires standardization of interfaces, robust network architectures, and rigorous testing of integrated systems. Ensuring that both physical and digital components operate harmoniously is key to the success of modern, smart technologies.

Additionally, employing modular designs and scalable architectures can facilitate easier integration and future upgrades. Collaboration among interdisciplinary teams, including hardware engineers, software developers, and data scientists, is also essential for addressing integration issues. By leveraging these strategies, engineers can develop more resilient and efficient systems that effectively combine physical and digital technologies.How might advancements in virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) transform the practical applications of physical technologies?

Answer: Advancements in VR and AR have the potential to transform practical applications of physical technologies by creating immersive and interactive experiences that bridge the gap between digital simulations and real-world operations. These technologies enable users to visualize complex systems in three dimensions, enhancing understanding and facilitating training, maintenance, and design processes. For instance, VR can simulate the operation of industrial machinery, allowing operators to practice in a risk-free environment, while AR can overlay digital information onto physical equipment to aid in repairs and diagnostics.

Additionally, VR and AR can be used for remote collaboration, where experts guide on-site personnel through complex procedures, thus improving efficiency and reducing downtime. As these technologies evolve, their integration with physical technologies will lead to more intuitive interfaces and smarter systems, driving innovation in sectors such as manufacturing, healthcare, and construction.What potential benefits can arise from the convergence of physical technologies and renewable energy systems?

Answer: The convergence of physical technologies and renewable energy systems offers significant benefits by creating more efficient, sustainable, and reliable energy solutions. Advances in materials, sensor technologies, and control systems can optimize the performance of renewable energy installations like solar panels and wind turbines. This integration enhances energy conversion efficiency, improves system resilience, and reduces operational costs, making renewable energy more competitive with traditional sources.

Moreover, the synergy between physical technologies and renewable energy supports the development of smart grids and energy storage systems that can adapt to fluctuating supply and demand. This leads to a more stable and sustainable energy infrastructure, which is essential for reducing carbon emissions and addressing climate change. As these technologies continue to evolve, they will play a crucial role in the global transition to cleaner energy sources.How can the analysis of spatial data enhance decision-making in the development of physical technologies?

Answer: The analysis of spatial data enhances decision-making in physical technologies by providing insights into geographic and environmental factors that influence system performance. Techniques such as Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and spatial statistics allow for the mapping, modeling, and optimization of physical processes across different locations. This spatial analysis is crucial for applications like urban planning, environmental monitoring, and infrastructure development, where location-specific information is key to efficient resource allocation and design.

By integrating spatial data with advanced analytical methods, decision makers can identify patterns and trends that inform better strategies for deploying physical technologies. This approach not only improves the accuracy of predictions but also supports the development of targeted solutions that address regional challenges, ultimately leading to more effective and sustainable outcomes.What are the challenges in measuring and ensuring the precision of physical sensors, and how can they be addressed?

Answer: Measuring and ensuring the precision of physical sensors involves overcoming challenges such as calibration errors, environmental interference, and signal noise. Precision is critical because even small inaccuracies can lead to significant errors in data analysis and system performance. Addressing these issues requires rigorous calibration procedures, the use of high-quality materials, and advanced signal processing techniques to filter out noise. Additionally, regular maintenance and testing are essential to ensure that sensors continue to perform reliably over time.

Innovations in sensor technology, including the development of self-calibrating and adaptive sensors, can further enhance precision. By integrating these advanced features with robust statistical methods for error correction, engineers can significantly improve the reliability and accuracy of sensor measurements, which is crucial for applications ranging from industrial automation to environmental monitoring.How might future trends in statistical analytics transform the field of physical technologies?

Answer: Future trends in statistical analytics, such as machine learning and big data integration, are expected to transform physical technologies by enabling real-time analysis and predictive modeling. These advancements allow for the continuous monitoring of system performance, identification of emerging trends, and proactive optimization of operational processes. Enhanced analytics provide deeper insights into complex data sets, facilitating more precise control and improved decision-making in physical systems.

Furthermore, the convergence of advanced statistical analytics with physical technologies will likely drive the development of adaptive systems that can learn from data and optimize their performance autonomously. This integration will not only increase efficiency but also pave the way for innovations in areas such as smart manufacturing, energy management, and autonomous robotics, fundamentally reshaping the technological landscape.

Last updated: