Treaty analysis offers a window into how states formalize cooperation, resolve disputes, and codify power relationships. Treaties are more than legal instruments—they are reflections of historical context, ideological currents, and shifting balances of power. Their origins and long-term impacts are shaped by the history of ideas, where philosophical debates on sovereignty, legitimacy, and international law have helped frame treaty norms for centuries.

Understanding treaties requires an appreciation of the systems in which they operate. The history of political systems shows how monarchies, empires, republics, and federations have crafted treaties to secure borders, define allies, and legitimize rule. These documents are closely tied to the history of political economy, where treaties often served to protect economic interests, secure trade routes, or establish access to resources and labor markets.

Trade agreements and economic arrangements fall within the realm of economic diplomacy, a critical subset of treaty-making that reflects not only cooperation but also competition. The legacy of such arrangements is central to economic history, where treaties enabled colonization, liberalized markets, or formalized reparations. These patterns often arose from underlying assumptions embedded in economic thought and theory.

Treaties frequently emerge during or after conflict. The economic history of warfare reveals how peace treaties have shaped reparations, territorial shifts, and military restrictions. In contrast, unconventional engagements—explored in guerrilla warfare and insurgency studies—often lead to fragile or asymmetric agreements negotiated under duress. More enduring treaties often result from long-term strategic partnerships, such as those examined in the history of alliances.

Ideological shifts and regime changes also influence treaty formation and abrogation. The drafting of revolutionary constitutions often introduces new legal standards for treaty validity, while the intellectual political history of a nation can reveal how domestic ideologies affect foreign commitments. These dynamics intersect with public opinion, often mobilized through history of social movements that advocate for or against treaty ratification.

Treaty analysis is not confined to state interests—it also reveals cultural, social, and symbolic dimensions. Religion has historically influenced the moral language of treaties, as explored in religious and spiritual history. Meanwhile, the framing of treaties in public discourse is reflected in popular culture, which shapes how societies remember diplomatic milestones.

Colonial legacies and power imbalances often endure in treaties, especially in the context of empire and decolonization. Postcolonial cultural studies critique how unequal treaties entrenched dependency and structured geopolitical hierarchies. These effects ripple into present-day policy, including electoral processes shaped by electoral history and undermined by electoral fraud and integrity.

On the domestic front, treaty obligations can affect labor protections and social welfare, as documented in labor and social policy. The historical record of treaties influencing working conditions, wages, and employment access is detailed in labor history. Education also plays a role, with education history highlighting how treaties are taught and interpreted across generations.

Finally, the rise of technology and industrialization has transformed treaty content and enforcement, a transformation traced in industrial and technological history. As global interdependence deepens, treaty analysis becomes ever more essential to understanding the legal architecture of the international system, offering deep insights into the dynamics that shape history itself.

This image depicts a formal diplomatic conference where representatives meet beneath a canopy of national flags and international symbols. In the foreground, a large document titled “Treaty Analysis” is being signed with a quill-like pen, emphasizing close reading, legal precision, and the importance of wording. The surrounding globe imagery suggests that treaties connect distant regions through shared rules—on peace, trade, borders, security, or the environment. The overall composition conveys treaty analysis as both legal and historical work: examining definitions, enforcement mechanisms, and hidden assumptions, while also considering the political context, bargaining strength, and strategic goals that shaped the final text.

Table of Contents

Fundamental Principles Behind Treaty Language and Logic

Definition and Purpose of Treaties

A treaty is a formal, legally binding agreement between states or international entities, often negotiated to address specific issues such as territorial disputes, trade relations, or collective security.

Core Objectives

- Conflict Resolution:

- Treaties often mark the end of wars and establish terms for peace.

- Example:

- The Treaty of Versailles (1919) formally ended World War I.

- Territorial Agreements:

- Define boundaries and resolve territorial disputes.

- Example:

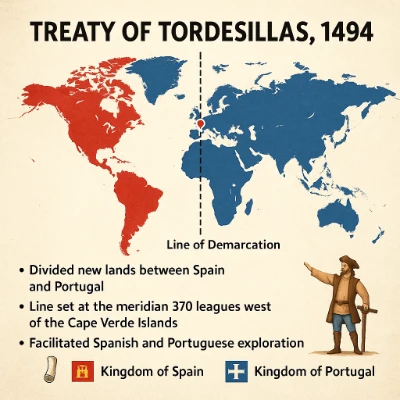

- The Treaty of Tordesillas divided the New World between Spain and Portugal.

- International Cooperation:

- Facilitate collaboration on global challenges such as trade, environmental protection, and human rights.

- Example:

- The Paris Agreement (2015) on climate change.

- Conflict Resolution:

Phases of Treaty Analysis

Negotiation

- Diplomatic Engagement:

- Negotiations often involve multiple parties balancing their interests.

- Example:

- The negotiations leading to the Treaty of Paris (1783) involved the United States, Great Britain, France, and Spain.

- Mediation and Arbitration:

- Neutral third parties may assist in resolving disputes.

- Example:

- The Treaty of Portsmouth (1905) ending the Russo-Japanese War was mediated by U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt.

- Diplomatic Engagement:

Drafting and Signing

- Legal Language:

- Treaties must use precise and unambiguous language to prevent misinterpretation.

- Signatories:

- Parties involved officially sign the treaty, committing to its terms.

- Legal Language:

Ratification

- Domestic Approval:

- Many treaties require legislative or parliamentary approval before they take effect.

- Example:

- In the U.S., treaties must be ratified by a two-thirds majority in the Senate.

- Domestic Approval:

Implementation

- Domestic and International Enforcement:

- States must incorporate treaty obligations into their legal and administrative systems.

- Monitoring Mechanisms:

- International organizations or joint commissions often oversee treaty compliance.

- Domestic and International Enforcement:

Consequences and Revisions

- Long-Term Impact:

- Treaties can reshape international relations and domestic policies.

- Example:

- The Treaty of Tordesillas influenced European colonization patterns for centuries.

- Long-Term Impact:

Pacts That Shaped the World: Defining Treaty Moments

This page launches an eight-part, chronologically ordered series of treaty deep-dives. Each entry moves beyond summary to analyze why the treaty emerged, how it worked (legal design, actors, and enforcement), and what it changed—politically, economically, and culturally. The set spans imperial expansion, sovereignty, industrial geopolitics, colonial partition, world wars, nuclear restraint, and climate governance.

- Treaty of Tordesillas (1494): Iberian powers partition the non-European world—cartography meets canon law, with enduring legacies from Brazil to the Moluccas.

- Peace of Westphalia (1648): Ends the Thirty Years’ War, foregrounding state sovereignty and non-interference—often framed as the birth of the modern international system.

- Treaty of Paris (1783): Confirms U.S. independence and redraws Atlantic power balances, with major implications for Indigenous nations and imperial economies.

- Congress of Vienna – Final Act (1815): Post-Napoleonic settlement that institutionalizes great-power concert, river commissions, and balance-of-power diplomacy.

- General Act of the Berlin Conference (1885): Codifies colonial “effective occupation” in Africa—legalizing partition and setting rules for imperial competition.

- Treaty of Versailles (1919): War-ending terms, mandates, reparations, and the League of Nations—punitive peace or necessary containment?

- Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons – NPT (1968): Bargain among nuclear restraint, peaceful use, and disarmament—verification and equity in tension.

- Paris Agreement (2015): Flexible, “bottom-up” climate treaty—ratcheting ambition, transparency frameworks, and the geopolitics of decarbonization.

Below is the first deep-dive; subsequent pages will follow this analytical template: Context → Parties & Interests → Text & Legal Mechanics → Implementation & Compliance → Distributional Effects → Global Impact → Critiques & Counterfactuals → Primary Sources & Further Reading → Discussion Prompts.

Treaty of Tordesillas (1494)

- Context:

- Signed between Spain and Portugal to divide newly discovered lands outside Europe.

- Terms:

- Established a demarcation line, granting Spain territories west of the line and Portugal those to the east.

- Impact:

- Influenced colonial expansion, with Portugal gaining control over Brazil while Spain dominated much of the Americas.

- Critique:

- Ignored the sovereignty of indigenous peoples, contributing to the exploitation and colonization of non-European societies.

Historical Context & Preludes

- Iberian rivalry: Late-15th-century maritime competition after Portuguese advances along the African coast and Columbus’s 1492 voyage under the Spanish crown.

- Papal bulls (1493): Alexander VI’s Inter caetera and related decrees attempted to settle claims by drawing an initial line west of the Azores/Cape Verde—Spain favored, Portugal protested.

- Diplomatic need: Avoid intra-Catholic war, lock in exclusive spheres for spice, gold, and conversion; translate papal moral authority into bilateral, enforceable terms.

Parties, Interests & Bargaining Leverage

- Crown of Castile/Aragon (Spain): Validate Columbus’s route, claim western lands, secure rights before rivals learned of the Atlantic crossing.

- Kingdom of Portugal: Protect Africa–Indian Ocean strategy (trade posts, Cape route), ensure eastern hemisphere priority, and obtain room in the western Atlantic for navigation and landfall.

- Hidden players: Papacy (moral-legal framing), emerging cartographers and pilots (practical measurement), and Indigenous polities (unconsulted but central to outcomes).

Key Terms & Legal Mechanics

- The Line: A meridian set 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde Islands. Because a “league” varied, longitude placement was ambiguous in practice.

- West/East allocation: Spain to the west (most of the Americas), Portugal to the east (Africa, Indian Ocean, and—crucially—an Atlantic slice touching future Brazil).

- Jurisdiction: Aimed at newly discovered lands; did not alter European borders.

- Enforcement: Royal licenses (asientos, captaincies), patrols, and later treaties; the Church’s authority gave initial legitimacy but practical power came from ships, forts, and courts.

Cartography, Science & the “Longitude Problem”

- Instruments & error: Latitude was measurable by stars; longitude at sea was imprecise until much later. Small measurement errors meant large territorial consequences.

- Map disputes: Competing charts (Iberian “secret” cartography) produced overlapping claims; the line’s exact meridian was contested on many voyage tracks.

- Follow-on settlement: The Treaty of Zaragoza (1529) extended a dividing line in the eastern hemisphere to address the Spice Islands (Moluccas) dispute.

Implementation & Compliance

- Portuguese Brazil: Landfalls along the South American bulge (early 1500s) fell on Portugal’s side of the line, enabling sugar, later gold, and plantation economies.

- Spanish America: Vast western claims underpinned viceroyalties (New Spain, Peru, later New Granada and Río de la Plata) and the encomienda system.

- Third-party powers: England, France, and the Dutch Republic rejected papal-bilateral partition; privateering and settlement (e.g., Caribbean islands) eroded the Iberian duopoly over the 16th–17th centuries.

Distributional Effects & Global Impact

- Economic: Iberian monopoly rents on spices, gold, and silver; global bullion flows (Potosí) destabilized European prices; Atlantic slave trade expanded with plantation complexes.

- Cultural–linguistic: Portuguese in Brazil vs. Spanish elsewhere in Latin America—a linguistic frontier traceable to the treaty line.

- Geopolitical: Set a precedent for “spheres” partition by great powers; normalized treaty-based claims to lands without Indigenous consent.

Indigenous Peoples & Ethical Critiques

- Sovereignty erased: The treaty treated inhabited territories as legally “available.” No Indigenous delegation participated; no recognition of existing legal orders.

- Labor & land expropriation: Encomienda and bandeirante slaving raids; missionization; epidemics; demographic collapse.

- Debates then & now: 16th-century Valladolid debate (Las Casas vs. Sepúlveda) on conquest morality; modern scholarship criticizes the papal “doctrines of discovery.”

Design Analysis: Why Did It “Work” (for a while)?

- Clarity + power: A simple rule (one meridian) plus two capable navies created enforceability—until other naval powers rose.

- Legitimation: Papal blessing eased domestic acceptance and deterred immediate contestation by Catholic rivals.

- Brittleness: Technical ambiguity (longitude) and exclusion of other powers/peoples generated long-term instability.

Counterfactuals & Alternatives

- If the line was set further west or east: Brazil’s shape—and language map—could have been radically different.

- Multilateralization in 1494: Had England/France been included (unlikely), piratical erosion and later wars might have been reduced—but Iberian dominance diluted sooner.

- Indigenous consent frameworks: A hypothetical (and anachronistic) recognition regime would have dramatically altered colonization’s speed, scale, and violence.

Primary Sources & Maps (Suggested)

- Papal bull Inter caetera (1493); the 1494 treaty text (Latin/Portuguese/Spanish versions).

- Early world maps (Cantino planisphere, 1502; Caverio, 1505) illustrating evolving understandings of the line.

- Treaty of Zaragoza (1529) for the eastern hemisphere counterpart.

Study Prompts & Exam-Style Questions

- Explain how technological limits in measuring longitude shaped the legal effectiveness of Tordesillas. Use one early map to support your answer.

- Compare Tordesillas with a later “spheres” treaty (e.g., Berlin 1885): What similar legal techniques and moral blind spots persist?

- Assess the treaty’s role in producing today’s Portuguese–Spanish linguistic boundary in the Americas. What non-treaty factors reinforced it?

Key Terms

Demarcation line; Papal bulls; Doctrine of discovery; Encomienda; Captaincy system; Longitude problem; Spheres of influence.

The graphic is a simplified world map shaded in two colors to illustrate the core idea of the Treaty of Tordesillas. Two vertical, dashed meridian lines suggest the demarcation line used by Spain and Portugal to claim exclusive spheres of exploration and conquest beyond Europe. A pin marks the Iberian Peninsula, while a small scroll and a cartoon explorer add a classroom style. A legend identifies red as the Kingdom of Spain and blue as the Kingdom of Portugal. The design is schematic rather than cartographically precise; it highlights the treaty’s outcome (for example, Portugal’s claim to Brazil fell on the “Portuguese” side of the line) and its historical significance. As with the original treaty, the map reflects a European partition that excluded and overrode the sovereignty of Indigenous peoples.

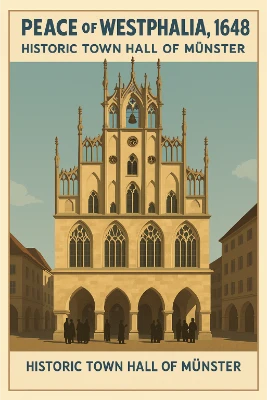

Peace of Westphalia (1648)

- Context (Baseline):

- Ended the Thirty Years’ War in the Holy Roman Empire and the Eighty Years’ War between Spain and the Dutch Republic.

- Concluded through parallel negotiations at Münster and Osnabrück.

Historical Context & War Drivers

- Religious fragmentation post-Reformation → dynastic/territorial rivalries (Habsburgs vs. Bourbons) → devastation across German lands.

- Mercenary warfare, famine, and disease produced catastrophic demographic and economic losses.

Main Parties & Interests

- Holy Roman Emperor & Imperial Estates: Reassert order while conceding local privileges.

- France & Sweden: Weaken Habsburg encirclement; gain territory and guarantor status.

- Spain & Dutch Republic: Settle independence and commerce (Spain recognizes Dutch independence).

- German Princes & Cities: Legal recognition of autonomy; religious rights; restitution of properties.

Treaty Set & Legal Mechanics

- Two core instruments: Treaty of Münster (Spain–United Provinces) and Treaty of Osnabrück/Münster (Empire–France–Sweden–Estates).

- Confessional settlement: Confirmed/updated the Peace of Augsburg with Calvinism recognized alongside Lutheranism and Catholicism.

- Territorial adjustments: Sweden gains Pomeranian territories; France gains Alsace/Lorraine rights; Swiss Confederacy & Dutch independence recognized de jure.

- Imperial constitution: Estates secure significant rights (treaty-making with caveats), embedding a negotiated federal order.

- Guarantee clauses: France and Sweden as guarantors—an early form of collective enforcement on paper.

Sovereignty & Non-Interference (Conceptual Legacy)

- Normalized the principle that rulers choose confessional settlement internally (with constraints) and external powers refrain from coercive interference.

- Precedent for diplomatic congresses and multi-lateral peace architecture in Europe.

Implementation & Compliance

- Restitution of secularized church properties; mixed confessional jurisdictions required local compromises.

- Guarantors’ enforcement was irregular—power politics still decisive (e.g., Louis XIV later wars).

Distributional Effects & Impact

- Ended large-scale religious war in central Europe; empowered estates; confirmed a multi-polarity enabling balance-of-power diplomacy.

- Commercial revival in the Dutch Republic; shifts in imperial trade/finance networks.

Caveats & Critiques

- “Westphalian sovereignty” is often overstated—interference and dynastic wars persisted; colonial domains ignored.

- Religious minorities still vulnerable within local majorities; peasantry saw limited immediate relief.

Counterfactuals

- A harsher imperial victory might have centralized the Empire; a French/Swedish collapse could have prolonged confessional warfare.

Primary Sources & Study Aids

- Treaty texts (Münster/Osnabrück); Imperial Diet records; confessional settlement provisions.

Prompts

- How did the treaty’s constitutional changes in the Empire shape later German fragmentation and unification timelines?

- Compare Westphalia’s guarantor model to later collective security arrangements.

Key Terms

Confessionalization; Imperial Estates; Guarantor clauses; Non-interference; Balance of power.

The graphic resembles a Wikipedia-style infobox titled “Peace of Westphalia” with a subheading “Treaties of Osnabrück and Münster.” A large central photograph shows the ornate façade of the historic town hall of Münster, the building where part of the settlement was concluded. Beneath the photo is a line of text: “The historic town hall of Münster where the treaty was signed.” A table lists key details: Type: Peace treaty. Context: Thirty Years’ War. Drafted: 1646–1648. Signed: 24 October 1648. Location: Osnabrück and Münster, Westphalia, Holy Roman Empire. Parties: 109. Languages: Latin. The layout emphasizes both the ceremonial venue and the legal metadata of the agreement.

The painting personifies the settlement of 1648: Time (winged elder with hourglass) ushers in a new era as a cornucopia pours out prosperity.

Mercury (commerce) and Neptune (safe seas) frame a robed ruler gesturing toward a flaming altar—symbols of oath-keeping and restored order.

Putti scatter garlands; river creatures and receding storm clouds suggest an end to devastation and the return of trade and fertility.

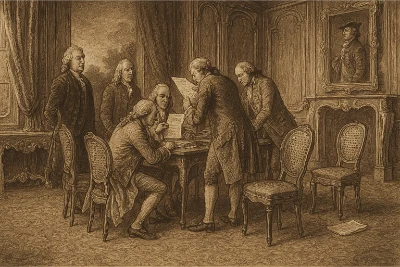

The scene encapsulates what the Treaties of Münster and Osnabrück promised: peace, lawful rule, and renewed economic life.Treaty of Paris (1783)

- Context (Baseline):

- Ended the American Revolutionary War; Great Britain recognizes the independence of the United States.

Geopolitical Setting

- Global war theater: North America, Caribbean, Atlantic; France and Spain seeking to check British power; the Netherlands drawn in.

- British war-weariness and fiscal strain fostered willingness to settle with the American peace commission.

Main Parties & Interests

- United States: Secure independence, generous borders, fishing rights, and debt recognition to reassure European creditors.

- Great Britain: Limit U.S. gains, preserve imperial trade, manage loyalist claims, and maintain strategic posts.

- France/Spain (related treaties): Territorial aims (e.g., Florida to Spain), naval prestige, and financial compensation.

- Indigenous nations: Excluded from talks despite centrality in the conflict and frontier future.

Key Terms & Legal Mechanics

- Recognition & Borders: U.S. borders to the Mississippi River; access to the Great Lakes; Florida returned to Spain (in separate treaty with Britain).

- Fisheries: U.S. rights on the Grand Banks and off Newfoundland and in the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

- Debts & Property: Private debts payable; “recommendation” (not obligation) to restore Loyalist property—seed of later disputes.

- Prisoners & Evacuation: British evacuation of posts; implementation lagged (e.g., forts in the Northwest Territory).

Implementation & Compliance

- Boundary commissions mapped complex river systems; British retention of frontier forts fueled tension until Jay Treaty (1794).

- Loyalist claims only partially addressed; many emigrated to Canada or Britain; compensation uneven.

- Indigenous land cessions accelerated via separate treaties—absent from the Paris text but consequential.

Distributional Effects & Impact

- U.S. sovereignty: International recognition enabled commercial treaties and credit access.

- Imperial rebalancing: Britain retained naval/commercial edge; France gained prestige but deepened fiscal crisis; Spain expanded in Florida but faced frontier strains.

- Indigenous dispossession: Expansionary borders set stage for rapid westward settlement and conflict.

Caveats & Critiques

- Ambiguities in the northwestern boundary; weak enforcement on Loyalist property; omission of Indigenous bargaining rights.

- Peace “on paper” preceded a decade of frontier violence and diplomatic friction.

Counterfactuals

- A stricter British stance on the Mississippi boundary could have constrained early U.S. expansion and altered Louisiana dynamics.

- Binding Loyalist restitution might have changed domestic U.S. politics and Anglo-American reconciliation pace.

Primary Sources & Study Aids

- Treaty text; boundary commission maps; Jay Treaty (1794) for follow-up compliance; Loyalist claims records.

Prompts

- Assess how the fisheries clauses reflect mercantilist logics and future maritime disputes.

- Explain the treaty’s indirect role in the fiscal unraveling of Bourbon France.

Key Terms

Recognition; Boundary commissions; Loyalists; Fisheries; Northwest Territory.

The image is a sepia, engraving-style scene set in a lavish Rococo room. A group of diplomats in knee-length coats and powdered wigs lean over a round table piled with parchment sheets and an inkstand with quills. One seated figure writes while others confer closely, pointing at a clause and exchanging notes. To the left, two envoys stand apart, observing; to the right, an empty chair holds a folded document while an additional sheet lies on the carpeted floor, suggesting hurried revisions. Carved wall panels, a marble fireplace with candelabra, and an oval portrait of a statesman frame the meeting. The composition emphasizes negotiation—bodies bent toward the paperwork, hands mid-gesture—evoking the painstaking, face-to-face process that produced landmark treaties of the late eighteenth century.

Congress of Vienna – Final Act (1815)

- Context (Baseline):

- Post-Napoleonic settlement reordering Europe; sought durable peace via balance of power and great-power concert.

Strategic Aims & Setting

- Undo Napoleonic conquests; contain France; prevent hegemon; stabilize borders; manage revolutionary contagion.

- Congresses and informal diplomacy (Talleyrand, Metternich, Castlereagh, Hardenberg, Nesselrode) crafted compromises.

Main Parties & Interests

- Austria/Metternich: Conservative order, buffer zones in Italy and the Balkans.

- Britain/Castlereagh: Maritime supremacy, trade routes, colonial gains; continental balance.

- Russia: Influence in Poland/Finland; status as liberator; Holy Alliance ideology (later).

- Prussia: Territorial consolidation in the Rhineland; path to German power.

- France/Talleyrand: Re-entry and status preservation via “legitimacy” principle.

Key Terms & Institutional Devices

- Territorial settlement: Dutch–Belgian union; Swiss neutrality; German Confederation replaces HRE; Italian states reconfigured.

- Concert of Europe: Periodic conferences, great-power consultations—proto collective management.

- Functional regimes: River commissions (Rhine) for navigation; rules on diplomatic precedence/courtesies.

- France: Restored Bourbon monarchy; moderate containment (post-Hundred Days adjustments).

Implementation & Compliance

- Concert managed crises (e.g., Greek independence, Belgian revolution) with mixed success; conservative interventionism contested.

- River commissions endured as early “functional international organizations.”

Distributional Effects & Long-Run Impact

- Relative stability in Europe for ~40 years; incentives for diplomatic crisis-management instead of general war.

- Laid groundwork for German/Italian unifications—unintended consequence of territorial consolidations.

Caveats & Critiques

- Legitimacy privileged dynastic rulers; popular sovereignty suppressed; colonial spheres unaddressed.

- Concert struggled with nationalist revolts and liberal movements; repression generated later upheavals.

Counterfactuals

- Harsher settlement on France might have provoked revanchism sooner; softer terms risked immediate instability.

Primary Sources & Aids

- Final Act; protocols; river commission statutes; diplomatic correspondence of major plenipotentiaries.

Prompts

- Evaluate the Concert as a governance innovation. What made it durable, and why did it ultimately falter?

- Compare Vienna’s river commissions to modern functional agencies (e.g., Danube Commission, ICAO analogies).

Key Terms

Balance of power; Legitimacy; Concert system; German Confederation; River commissions.

The image depicts a ceremonial negotiation chamber filled with hundreds of delegates in blue and red uniforms with gold braid and sashes. At center, leading envoys lean over a broad table draped with rich fabric and imperial emblems, studying a pastel map of Europe while a brass-armillary globe stands beside stacked treaty folios, quills, and seals. Seated statesmen listen as others point at the map and exchange documents. In the background, a neoclassical niche shows Lady Justice with scales, symbolizing legality and order. The crowded composition emphasizes multilateral bargaining after Napoleon’s defeat: the settlement aimed to contain France, stabilize frontiers, integrate great-power guarantees, and institutionalize cooperation through the emerging Concert of Europe.

General Act of the Berlin Conference (1885)

- Context (Baseline):

- European powers codified rules for African colonization amid the “Scramble for Africa.”

Setting & Motives

- Commercial access (rivers/coasts), raw materials, strategic competition; humanitarian rhetoric vs. imperial practice.

- Belgian, French, British, German ambitions intersecting along Congo and West African coasts.

Main Parties & Interests

- Germany (Bismarck) as convenor; Britain & France as major naval powers; Portugal, Belgium, Italy, Spain, and others attending.

- Notably absent: African polities had no seat at the table.

Key Terms & Doctrines

- “Effective occupation”: Claims require administrative presence to be recognized—legal cover for rapid partition.

- Free trade/navigation: Congo and Niger river basins declared open for commerce (on paper).

- Humanitarian clauses: Pledges against the slave trade—often instrumentalized to justify imperial control.

- Congo Free State: Leopold II’s personal domain internationally recognized—site of extreme exploitation.

Implementation & Compliance

- “Effective occupation” spurred military conquest and boundary-drawing with scant knowledge of local societies.

- River free trade constrained by de facto monopolies; humanitarian pledges routinely violated.

- Boundary commissions drew straight lines ignoring ethnic/linguistic realities, planting seeds for later conflicts.

Distributional Effects & Global Impact

- Consolidated European imperial rule; extraction economies; forced labor; demographic and social upheaval.

- Long-run state borders in Africa trace to colonial demarcations with legacies for governance and conflict.

Caveats & Ethical Critiques

- Legalized dispossession; erased African sovereignty; “civilizing” rhetoric masked commercial coercion and violence.

- Congo atrocities catalyzed early international human rights advocacy but after immense harm.

Counterfactuals

- Multilateral protectorates with African representation could have moderated exploitation (speculative given the era’s power asymmetries).

- Absent the Act, partition likely via bilateral wars—perhaps even bloodier.

Primary Sources & Aids

- General Act text; boundary protocols; consular reports; missionary accounts; later Congo reform movement documents.

Prompts

- Analyze “effective occupation” as a legal technology: how did it reshape incentives at the frontier?

- Trace a contemporary border dispute to Berlin’s lines—what institutional fixes might mitigate the legacy?

Key Terms

Effective occupation; Free navigation; Protectorate; Boundary commission; Congo Free State.

The illustration shows a neoclassical reception room packed with uniformed envoys and statesmen. At center, two senior delegates clasp hands while others lean over a broad table strewn with parchment, an inkwell, measuring rulers, and a large map of Africa. Secretaries sit behind them recording clauses; additional delegates confer in small clusters along the walls beneath arched windows and carved pilasters. The crowded composition emphasizes ceremony and great-power consensus. Equally striking is the absence of African representation, underscoring how the General Act of 1885 legalized imperial claims through the doctrine of “effective occupation,” promised free trade/navigation on major rivers, and recognized Leopold II’s Congo Free State—arrangements that enabled accelerated conquest and extraction despite their humanitarian language.

Treaty of Versailles (1919)

- Context (Baseline):

- Formally ended WWI with Germany; created League of Nations; redrew borders; imposed reparations and disarmament.

Negotiating Environment

- Allied objectives varied: French security/compensation, British balance/economic recovery, U.S. Wilsonian principles (self-determination, League).

- German delegation excluded from early drafting; armistice expectations vs. treaty realities fueled resentment.

Key Terms & Architecture

- Territory: Alsace-Lorraine to France; Polish corridor & Danzig Free City; Saar under League administration; colonies as mandates.

- Military limits: Army capped; no tanks/air force; Rhineland demilitarized.

- Reparations: Liability established; sums and schedules contentious; Reparations Commission oversight.

- League of Nations: Collective security framework; U.S. Senate rejection undermined universality.

- War guilt clause: Legal basis for reparations; symbolically explosive in German politics.

Implementation & Compliance

- Inter-Allied control commissions enforced disarmament; reparations oscillated (Dawes Plan 1924; Young Plan 1929); defaults and crises.

- Locarno (1925) eased tensions on western frontiers; Great Depression destabilized compliance and politics.

Distributional Effects & Impact

- Short-term: border changes, minority issues, economic volatility; mandate system entrenched imperial oversight under international veneer.

- Long-term: grievances exploited by extremists; failures of collective security—precursors to WWII.

Caveats & Historiography

- Debate over “punitive” vs. “moderate” terms: some argue Versailles was not as harsh as alleged compared to alternative demands.

- Structure of enforcement (and U.S. absence) arguably more fatal than clause severity alone.

Counterfactuals

- U.S. League membership + stable reparations regime might have sustained Weimar moderation longer.

- Earlier revision of eastern borders could have reduced interwar minority crises—speculative.

Primary Sources & Aids

- Treaty text; Reparations Commission records; League Covenant; Locarno Treaties; Weimar political debates.

Prompts

- Which mattered more for instability: reparations design or security architecture? Argue with evidence.

- Compare the mandate system to earlier colonial legalities (e.g., Berlin 1885) in rhetoric vs. practice.

Key Terms

Mandates; Reparations; Demilitarization; Self-determination; Collective security.

The image is a wide, oil-painting–style impression of the signing ceremony in the Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles. Hundreds of diplomats and officials in dark suits fill the gilded gallery beneath a painted barrel vault. Long tables draped in red cloth form a central aisle where secretaries prepare documents and senior delegates step forward to sign. Natural light pours through the tall windows on the left while marble pilasters, mirrors, and classical statues line the right wall. The crowded composition conveys ceremony and gravity—after years of war, the Allied powers finalize terms that limit Germany’s military, mandate colonial territories, set up reparations, and create the League of Nations, even as debate over fairness and enforcement lingers in the faces turned toward the dais.

Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (1968)

- Context (Baseline):

- Cold War arms race spurred multilateral effort to limit nuclear spread, promote peaceful use, and pursue disarmament.

Bargain Structure (“Three Pillars”)

- Non-proliferation: Non-nuclear-weapon states (NNWS) renounce weapons; nuclear-weapon states (NWS) not to assist proliferation.

- Peaceful use: Access to nuclear technology for energy/medicine under safeguards.

- Disarmament: Commitment to negotiations toward cessation of the arms race and disarmament (Article VI).

Key Terms & Enforcement

- Definitions: NWS = states that tested before 1 Jan 1967 (US, USSR/Russia, UK, France, China); others are NNWS.

- IAEA Safeguards: Verification via inspections, material accountancy; later Additional Protocol expands access.

- Export controls: Supplier groups coordinate technology transfer restrictions.

- Withdrawal clause (Art. X): Right with notice—rare but consequential precedent.

Implementation & Compliance

- Extensive accession; cases of non-compliance spurred sanctions/diplomacy; safeguard regimes strengthened over time.

- NWS disarmament progress uneven; bilateral arms control outside NPT architecture has been pivotal.

- Outliers (non-parties/withdrawals) challenge universality and regional security dynamics.

Efficacy & Distributional Effects

- Limited the number of nuclear-armed states relative to feared projections in the 1960s.

- Created technology access pathways but also inequity debates (have/have-not structure).

- Regional security complexes (Middle East, South Asia, Northeast Asia) remain fragile.

Caveats & Critiques

- Article VI implementation: perceived slow disarmament by NWS undermines legitimacy.

- Peaceful use vs. latent capability tension: enrichment/reprocessing can shorten breakout timelines.

- Export control disparities and technology denial concerns in developing states.

Counterfactuals

- No NPT world likely features dozens of nuclear-armed states; crisis stability much worse.

- A stronger verification regime from the start (e.g., universal Additional Protocol) might have prevented notorious violations—but may have deterred early accessions.

Primary Sources & Aids

- Treaty text; IAEA safeguards agreements; Review Conference outcome documents; export control guidelines.

Prompts

- Is the NPT’s inequitable structure a necessary bargain or a design flaw? Propose reforms that could pass politically.

- Assess the role of verification innovations vs. security guarantees in preventing proliferation.

Key Terms

IAEA safeguards; Additional Protocol; Breakout; Export controls; Article VI.

The artwork depicts a massive, olive-drab missile canister mounted on an eight-axle transporter-erector-launcher moving across a paved square. Dust curls around the heavy tires as smaller armored vehicles follow. The launcher’s cab bristles with equipment; the cylindrical payload fairing dominates the composition. Ornate civic buildings rise behind the convoy, situating the scene in a ceremonial urban setting. The painting emphasizes scale, engineering detail, and the performative aspect of nuclear deterrence—how nuclear states publicly display strategic systems to signal readiness and resolve while avoiding actual use.

Paris Agreement (2015)

- Context (Baseline):

- Landmark climate treaty under UNFCCC aiming to limit global temperature rise to well below 2°C, pursuing efforts toward 1.5°C.

Design Philosophy: Bottom-Up with Common Rules

- Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs): Each party submits its own targets/policies—flexibility to secure universal participation.

- Ratcheting mechanism: 5-year cycles to enhance ambition; global stocktake informs updates.

- Transparency framework: Common reporting/verification (flexibility for capacity) to build trust and comparability.

Key Provisions

- Mitigation: Long-term low-GHG strategies; peaking emissions ASAP; balance sources/sinks in 2nd half of century.

- Adaptation: National adaptation plans; resilience building; adaptation communications.

- Finance: Developed countries to provide/support finance flows; mobilization goal (outside the legal core text).

- Loss & Damage: Recognition via Warsaw International Mechanism; politics of liability/compensation remain sensitive.

- Cooperative approaches (Art. 6): Carbon markets and non-market cooperation with accounting safeguards (corresponding adjustments, double-counting prevention).

Implementation & Compliance

- Enhanced Transparency Framework (common tables, expert review); global stocktakes at 5-year intervals.

- Non-punitive compliance committee focuses on facilitation and capacity, not sanctions—consensus choice to keep parties in.

- Sub-national/private actors pivotal (cities, companies), creating polycentric governance beyond states.

Efficacy, Equity & Politics

- Aggregate NDCs currently insufficient for 1.5°C; ratchet success hinges on finance, technology diffusion, and domestic politics.

- Equity disputes: historical responsibility vs. current/future emissions; just transition for workers and regions.

- Geopolitics of clean tech, supply chains (critical minerals), and border adjustments reshape trade diplomacy.

Caveats & Critiques

- Voluntary ambition risks free-riding; transparency helps but cannot compel stronger targets.

- Finance credibility gaps undermine trust; measurement issues for offsets and Article 6 integrity.

Counterfactuals

- A top-down Kyoto-style binding target for all would likely have failed politically; Paris trades legal bite for breadth and durability.

- Stronger Article 6 safeguards from day one might have improved integrity but slowed consensus.

Primary Sources & Aids

- Paris Agreement text; NDC registry; global stocktake outcomes; IPCC assessments as scientific underpinning.

Prompts

- Design a credible ratchet pathway for a major emitter that aligns with 1.5°C and domestic political constraints.

- Evaluate Article 6 risks and propose guardrails to prevent greenwashing while enabling cooperation.

Key Terms

NDCs; Global stocktake; Enhanced Transparency Framework; Article 6; Loss & Damage; Just transition.

Delegates celebrate adoption of a global climate pact built on nationally determined contributions, five-year ratchets, transparency rules, and support for adaptation and resilience.

A celebratory conference scene with officials standing behind a long desk, hands raised together beneath a banner reading “Global Climate Conference 2015 • Paris.” Nameplates label roles like President and UN Secretariat; microphones and documents rest on the table. The picture evokes the adoption of the Paris Agreement’s core features—NDCs, five-year ambition cycles, transparency, and attention to adaptation and loss-and-damage—while remaining an illustrative artist impression, not a historical photograph.

Themes in Treaty Analysis

Power Dynamics

- Treaties often reflect the power imbalance between negotiating parties.

- Example:

- The Treaty of Nanking (1842) imposed unequal terms on China after its defeat in the First Opium War.

Sovereignty and Autonomy

- Treaties can strengthen or undermine state sovereignty.

- Example:

- The Treaty of Waitangi (1840) between Britain and Māori chiefs in New Zealand remains contentious, with debates over its interpretation and implementation.

Regional and Global Impacts

- Treaties often have far-reaching consequences beyond their immediate terms.

- Example:

- The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) reshaped trade dynamics across North America.

Challenges in Treaty Negotiation and Implementation

Complexity of Multilateral Agreements

- Multilateral treaties often involve diverse interests, making consensus difficult.

- Example:

- The Kyoto Protocol faced challenges due to varying commitments among developed and developing nations.

Non-Compliance

- States may fail to fulfill treaty obligations due to domestic or external pressures.

- Example:

- Some signatories of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) have been accused of violating its terms.

Lack of Enforcement Mechanisms

- Many treaties rely on voluntary compliance, limiting their effectiveness.

- Example:

- The League of Nations failed to prevent aggression by Axis powers before World War II.

Reading Between the Lines: Practical Uses of Treaty Interpretation

Conflict Resolution

- Treaties are essential tools for ending conflicts and establishing frameworks for peace.

- Example:

- The Good Friday Agreement (1998) brought peace to Northern Ireland after decades of conflict.

Environmental Protection

- International treaties address global challenges such as climate change and biodiversity loss.

- Example:

- The Montreal Protocol (1987) successfully reduced ozone-depleting substances.

Trade and Economic Development

- Trade agreements facilitate economic integration and growth.

- Example:

- The European Union’s foundational treaties established a single market and customs union.

Why Treaties Matter: Decoding the Frameworks of Peace and Power

Understanding the Legal Foundations of International Relations

Exploring the Structure, Language, and Interpretation of Treaties

Analyzing Historic and Contemporary Agreements

Recognizing the Role of Treaties in Conflict Prevention and Cooperation

Preparing for Academic and Professional Paths in Law, Diplomacy, and Policy

Beyond the Agreement: Last Reflections on Treaty Function

The study of treaties reveals their critical role in shaping international relations, resolving disputes, and addressing global challenges. From historical agreements like the Treaty of Tordesillas to contemporary accords like the Paris Agreement, treaties have defined political boundaries, ended wars, and fostered cooperation among nations. However, their success depends on effective negotiation, equitable terms, and robust enforcement mechanisms. By analyzing treaties, we can better understand the complexities of diplomacy, the challenges of implementation, and their far-reaching consequences for global governance.

Frequently Asked Questions – Treaty Analysis

What is treaty analysis?

Treaty analysis is the systematic study of international agreements to understand their language, context, negotiation history, implementation, and impact. It combines legal interpretation with historical and political analysis to see how treaties are made, how they function, and how they reshape relations between states and other actors.

Why is treaty analysis important in diplomatic history?

Treaties are key products of diplomacy, often marking turning points such as the end of wars, the creation of alliances, or the establishment of international organisations. Treaty analysis helps explain why agreements took the form they did, whose interests they served, and how they influenced later conflicts, cooperation, and legal norms.

What are the main elements examined in treaty analysis?

Treaty analysis usually considers the treaty text, the historical context of negotiation, the parties involved, their relative power, the drafting process, reservations and protocols, mechanisms for enforcement or dispute settlement, and how the agreement has been interpreted and applied over time by courts, governments, and international bodies.

How do power relations shape the content of treaties?

Powerful states often have more leverage in setting agendas, drafting clauses, and enforcing compliance, which can tilt treaties in their favour. However, weaker states, coalitions, and non-state actors can still influence outcomes through bargaining, norm-based arguments, issue-linkage, and strategic use of international institutions in the negotiation process.

How is analysing a bilateral treaty different from analysing a multilateral treaty?

Bilateral treaties primarily reflect the interests and compromises of two parties, making their dynamics more focused but sometimes more asymmetrical. Multilateral treaties involve many actors with diverse preferences, require complex drafting, and often create general rules or institutions. Treaty analysis compares how bargaining, coalition-building, and enforcement differ across these formats.

Why does treaty analysis pay attention to implementation and compliance?

A treaty’s significance depends not just on what is written, but on how far its provisions are implemented in practice. Treaty analysis asks whether parties change laws, policies, and behaviour, what monitoring and enforcement mechanisms exist, and how disputes over non-compliance are handled, revealing gaps between formal commitments and real outcomes.

What kinds of sources are used to study treaties historically?

Historians examine treaty texts, preparatory works and draft versions, diplomatic correspondence, minutes of conferences, legal opinions, parliamentary debates, memoirs of negotiators, and court decisions. These sources help reconstruct negotiation strategies, hidden trade-offs, contested meanings, and the evolving interpretation of treaty obligations.

How do legal interpretation and historical context work together in treaty analysis?

Legal interpretation focuses on the wording, structure, and agreed rules for reading treaties, while historical context explains why certain phrases were chosen and how contemporaries understood them. Combining both approaches helps avoid reading today’s assumptions into past texts and clarifies how meaning may have shifted over time.

What challenges commonly arise when interpreting treaties?

Common challenges include vague or ambiguous language, conflicting provisions, translation issues, secret clauses, and changing circumstances not anticipated by drafters. Treaty analysis must also consider that different parties may have had divergent expectations, leading to later disputes about the “true” meaning of key terms.

How does treaty analysis connect to broader themes in diplomatic and international history?

Treaty analysis connects legal texts with larger themes such as empire, decolonisation, human rights, economic globalisation, alliance politics, and institutional design. It shows how treaties both reflect and reshape power structures, ideologies, and economic interests across different periods of international history.

What skills can students gain from learning how to analyse treaties?

Students develop skills in close reading, legal reasoning, historical contextualisation, and critical evaluation of sources. They learn to dissect complex documents, trace negotiations, and assess the real-world effects of international agreements, preparing them for advanced study in history, law, international relations, and policy work.

How can this Treaty Analysis page be used with other Prep4Uni resources?

Learners can link this Treaty Analysis page with materials on diplomatic history, the history of alliances, economic diplomacy, international law, and specific regional or thematic case studies. Exploring these resources together helps students see how detailed treaty work fits into wider narratives of conflict, cooperation, and institutional change.

Treaty Talk: Quiz Yourself on Diplomatic Agreements

1. What is treaty analysis and why is it important in diplomatic history?

Answer: Treaty analysis is the systematic study of the formation, content, and impact of international agreements, which are central to diplomatic history. It examines the negotiation processes, language, and implementation of treaties, shedding light on how states articulate and secure their interests. This analytical approach reveals the underlying power dynamics and legal principles that guide international relations. Understanding treaty analysis is crucial as it helps explain the evolution of global diplomacy and the development of international law.

2. How do treaties serve as tools for conflict resolution in international relations?

Answer: Treaties serve as essential tools for conflict resolution by formalizing agreements that resolve disputes between nations through peaceful means. They establish clear rules and mechanisms for cooperation and conflict management, reducing the potential for misunderstandings and hostilities. Through treaties, states can commit to mutual security arrangements and economic partnerships that promote stability and prevent future conflicts. This process of negotiated compromise and legally binding commitments plays a pivotal role in maintaining global peace and fostering international cooperation.

3. What factors influence the negotiation and formulation of treaties?

Answer: The negotiation and formulation of treaties are influenced by a range of factors including political interests, economic conditions, cultural differences, and power asymmetries between nations. Diplomatic negotiations often reflect the strategic priorities of the parties involved, with each side seeking to maximize its benefits while mitigating risks. Additionally, historical context and external pressures, such as regional conflicts or global economic trends, shape the substance and tone of treaty negotiations. These factors collectively determine the effectiveness and longevity of the resulting agreements.

4. How do historians use treaty analysis to understand shifts in international power?

Answer: Historians use treaty analysis to understand shifts in international power by examining how the terms and enforcement of treaties reflect changes in geopolitical dynamics over time. Analyzing treaties allows scholars to track the rise and fall of empires, the emergence of new alliances, and the rebalancing of global power structures. Treaties often serve as markers of political transitions, revealing how diplomatic strategies have evolved to address changing economic, military, and cultural circumstances. This approach provides a nuanced understanding of international relations and the mechanisms by which nations assert their influence on the world stage.

5. In what ways can treaty language reveal the intentions and priorities of negotiating parties?

Answer: Treaty language is a key indicator of the intentions and priorities of negotiating parties, as the precise wording reflects the compromises and strategic interests underlying the agreement. Diplomatic negotiators carefully craft language to balance conflicting objectives, signal commitment, and manage future disputes. Specific terms, clauses, and exceptions often reveal the relative bargaining power of each side and the issues deemed most critical to their national interests. Analyzing this language allows historians and legal scholars to interpret the broader context of international negotiations and understand how agreements were designed to address both immediate concerns and long-term objectives.

6. How does treaty analysis contribute to our understanding of international legal frameworks?

Answer: Treaty analysis contributes to our understanding of international legal frameworks by providing insights into how binding agreements shape the norms and rules that govern state behavior. Treaties form the backbone of international law, setting standards for issues such as trade, human rights, and environmental protection. Through detailed analysis of treaty provisions and their implementation, scholars can discern how international legal principles evolve and influence global governance. This study helps to illuminate the interplay between legal norms and diplomatic practice, demonstrating the role of treaties in promoting peace and stability across borders.

7. What challenges do scholars face when interpreting historical treaties?

Answer: Scholars face several challenges when interpreting historical treaties, including language ambiguities, incomplete archival records, and differing cultural contexts that influence the meaning of treaty provisions. Variations in legal terminology over time can complicate efforts to understand the original intent of the negotiators. Additionally, treaties are often products of their historical and political context, requiring careful analysis to separate symbolic language from legally binding commitments. These challenges necessitate a multidisciplinary approach that combines historical research, legal analysis, and contextual interpretation to accurately assess the significance of treaties in diplomatic history.

8. How can treaty analysis reveal the evolution of diplomatic negotiation techniques?

Answer: Treaty analysis reveals the evolution of diplomatic negotiation techniques by tracing changes in the methods, language, and strategies used in international agreements over time. By comparing treaties from different historical periods, scholars can identify shifts in negotiation styles, such as the move from informal, personal diplomacy to formal, institutionalized negotiations. This evolution reflects broader changes in international relations, including the development of multilateral institutions and the increasing complexity of global challenges. Through this analysis, we gain a deeper understanding of how diplomatic practices have adapted to changing political, economic, and cultural conditions.

9. How do economic considerations manifest in the language and content of treaties?

Answer: Economic considerations manifest in treaties through provisions related to trade, investment, resource allocation, and financial cooperation. The specific language used in treaties often reflects the economic priorities of the negotiating parties, outlining tariffs, quotas, and other regulatory measures designed to protect domestic industries or promote free trade. Economic clauses can also include mechanisms for dispute resolution, ensuring that economic interests are safeguarded over the long term. Analyzing these aspects of treaty language provides insights into how economic power influences international relations and how states seek to secure mutual economic benefits through diplomatic negotiation.

10. How might the study of treaty analysis inform contemporary diplomatic strategies and international policymaking?

Answer: The study of treaty analysis informs contemporary diplomatic strategies and international policymaking by offering lessons on effective negotiation, compromise, and the management of complex international agreements. By understanding the successes and failures of historical treaties, diplomats can design strategies that better address current global challenges such as trade disputes, environmental issues, and security concerns. This analysis also highlights the importance of clarity, transparency, and flexibility in treaty language, which are critical for ensuring that agreements remain robust and adaptable. Ultimately, the insights gained from treaty analysis help shape policies that promote stability, foster cooperation, and advance the interests of nations in an interconnected world.

Lines of Agreement or Lines of Conflict? Critical Treaty Inquiries

1. How might emerging digital technologies revolutionize the way treaties are negotiated and implemented in international diplomacy?

Answer: Emerging digital technologies, such as blockchain and artificial intelligence, have the potential to revolutionize the negotiation and implementation of treaties by enhancing transparency, efficiency, and trust among negotiating parties. Blockchain technology can provide a secure, decentralized ledger for recording treaty negotiations, ensuring that all parties have access to an immutable record of agreements and amendments. This transparency can reduce disputes over interpretations and enhance compliance, as any changes to the treaty would be publicly verifiable. AI can further streamline the negotiation process by analyzing vast amounts of data to identify potential areas of compromise and predict the outcomes of different negotiation strategies.

Additionally, digital technologies can facilitate real-time collaboration among diplomats, enabling faster decision-making and more agile responses to changing geopolitical dynamics. Virtual reality platforms, for example, could simulate negotiation scenarios, allowing parties to experiment with different approaches in a risk-free environment. These technological advancements not only modernize the process of treaty negotiation but also create opportunities for more inclusive and participatory diplomacy. As a result, future international agreements may be characterized by greater efficiency, enhanced mutual trust, and a more dynamic, responsive framework for global governance.

2. How can comparative treaty analysis help in understanding the evolution of international legal norms?

Answer: Comparative treaty analysis helps in understanding the evolution of international legal norms by examining how different treaties from various historical periods and regions have addressed common issues and shaped global legal frameworks. By comparing treaties, scholars can trace the development of key principles such as sovereignty, non-intervention, and human rights, identifying patterns that illustrate how international law has adapted to new challenges over time. This analysis reveals how changes in diplomatic practices, technological advancements, and shifting power dynamics have influenced the formulation of treaties, leading to the gradual emergence of a cohesive set of international legal standards.

Furthermore, comparative treaty analysis provides insights into the interplay between domestic legal traditions and international norms, highlighting the ways in which cultural and historical contexts shape the interpretation and implementation of treaties. This interdisciplinary approach enriches our understanding of international law by demonstrating that legal norms are not static but are continually negotiated and redefined through diplomatic engagement. By learning from diverse treaty experiences, policymakers can design more effective legal instruments that are adaptable to the evolving global landscape, ensuring that international legal frameworks remain robust and relevant.

3. How might the historical context of treaty negotiations influence contemporary diplomatic practices?

Answer: The historical context of treaty negotiations influences contemporary diplomatic practices by providing a rich source of lessons on negotiation tactics, power dynamics, and conflict resolution strategies. Past treaty negotiations often occurred under conditions of significant geopolitical tension, where diplomats had to navigate complex relationships and competing interests. These historical experiences reveal the importance of timing, compromise, and the use of third-party mediation in achieving successful outcomes. Understanding the context in which earlier treaties were negotiated can inform modern diplomatic strategies by highlighting effective approaches to overcoming impasses and building consensus among diverse parties.

In contemporary settings, this historical perspective can guide diplomats in managing similar challenges by adapting proven negotiation techniques to current realities. For example, lessons learned from historical alliances and conflict resolution efforts can be applied to modern trade negotiations or environmental agreements, where the stakes are equally high. The continued study of historical treaty contexts provides a blueprint for developing strategies that are both innovative and grounded in established diplomatic practices, ultimately contributing to more effective and enduring international agreements.

4. How can treaty analysis be used to evaluate the effectiveness of international conflict resolution mechanisms?

Answer: Treaty analysis can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of international conflict resolution mechanisms by examining the terms, implementation, and long-term impacts of treaties designed to resolve disputes. Through a detailed analysis of treaty language and negotiation processes, scholars can assess whether the agreements have successfully addressed the underlying causes of conflict and established durable frameworks for cooperation. This evaluation involves studying the enforcement mechanisms, dispute resolution procedures, and compliance records associated with the treaties, providing a comprehensive view of their performance over time.

Furthermore, comparing different treaties can reveal best practices and identify common shortcomings in international conflict resolution. Such analysis can inform the development of more robust mechanisms by highlighting factors that contribute to successful outcomes, such as transparency, inclusivity, and adaptability. By integrating these findings into modern diplomatic strategies, policymakers can design more effective conflict resolution frameworks that not only resolve disputes but also foster long-term peace and stability. This evidence-based approach is critical for advancing international law and ensuring that conflict resolution mechanisms remain responsive to emerging global challenges.

5. How might economic incentives be used as a diplomatic tool in treaty negotiations?

Answer: Economic incentives can be used as a diplomatic tool in treaty negotiations by offering tangible benefits that encourage cooperation and compromise among nations. These incentives might include favorable trade terms, investment opportunities, or financial aid, which can help to offset the perceived costs of entering into an agreement. By providing economic benefits, states can create a win-win scenario that enhances mutual trust and fosters long-term collaboration. The strategic use of economic incentives not only helps to secure favorable treaty terms but also strengthens the overall economic ties between negotiating partners, thereby contributing to greater regional and global stability.

In practice, economic incentives are often integrated into treaties as clauses that offer specific benefits contingent upon compliance with the agreement. This approach ensures that economic interests are aligned with diplomatic objectives, making it more likely that all parties will adhere to the treaty. Historical examples of successful economic diplomacy demonstrate that well-designed incentives can transform contentious negotiations into cooperative endeavors, paving the way for enduring international partnerships. As global economic interdependence grows, the role of economic incentives in treaty negotiations is likely to become even more critical in shaping the future of international relations.

6. How can interdisciplinary research enhance our understanding of the negotiation processes behind major treaties?

Answer: Interdisciplinary research can enhance our understanding of the negotiation processes behind major treaties by integrating insights from history, political science, economics, psychology, and law. This approach allows scholars to examine the multifaceted aspects of treaty negotiations, including the economic interests, political dynamics, and psychological factors that influence decision-making. By combining quantitative data with qualitative analysis, interdisciplinary research can uncover patterns and underlying motivations that traditional approaches might overlook. This comprehensive perspective provides a richer and more nuanced understanding of how treaties are negotiated and the strategies that lead to successful outcomes.

Moreover, interdisciplinary studies can help identify the broader societal impacts of treaty negotiations, revealing how these processes affect public opinion, political stability, and international cooperation. By exploring the interplay between individual personalities, institutional frameworks, and external pressures, researchers can develop more robust models of negotiation behavior. These insights not only inform academic theory but also offer practical guidance for diplomats and policymakers seeking to improve future negotiation strategies. Ultimately, the integration of multiple disciplines leads to a deeper and more holistic understanding of international diplomacy and conflict resolution.

7. How might emerging global issues, such as cybersecurity and climate change, influence the content and focus of future treaties?

Answer: Emerging global issues like cybersecurity and climate change are poised to significantly influence the content and focus of future treaties by necessitating new legal frameworks and cooperative strategies among nations. Cybersecurity threats and digital conflicts require treaties that establish norms for state behavior in cyberspace, including protocols for information sharing, cyber defense, and the protection of critical digital infrastructure. Similarly, the pressing challenges of climate change call for international agreements that set binding emission targets, promote renewable energy, and facilitate the transfer of green technologies. These emerging issues are reshaping international priorities and compelling nations to negotiate treaties that address both economic and environmental dimensions of global governance.

The integration of these issues into treaty negotiations will likely lead to more comprehensive and multifaceted agreements that reflect the interconnected nature of modern challenges. Future treaties may need to incorporate mechanisms for monitoring compliance, enforcing standards, and providing technical and financial support to developing nations. This evolution in treaty content will require diplomats to balance national interests with global responsibilities, ultimately fostering a more resilient and cooperative international order. As these challenges intensify, the adaptability of diplomatic practices will be crucial in ensuring that treaties remain relevant and effective in promoting collective security and sustainable development.

8. How can the study of treaty language help us understand the priorities and power dynamics among negotiating nations?

Answer: The study of treaty language can provide deep insights into the priorities and power dynamics among negotiating nations by revealing the nuances of negotiation strategies and the underlying interests of the parties involved. Specific wording, clauses, and exceptions in treaties often reflect the concessions made and the bargaining power of each side, offering clues about which issues were deemed most critical. Analyzing the language used in treaties allows scholars to decipher how negotiators balanced competing demands, managed asymmetries in power, and secured commitments that aligned with their national interests. This detailed linguistic analysis is crucial for understanding the strategic considerations that drive international agreements and the complex interplay between cooperation and competition.

Additionally, treaty language can serve as a historical record of diplomatic negotiations, capturing the evolution of international norms and the shifting priorities of global politics. By comparing treaties from different periods or regions, researchers can identify patterns that illustrate how power dynamics have changed over time. This understanding not only enriches academic scholarship but also informs modern diplomatic practices by highlighting effective communication strategies and negotiation tactics that can be applied in current and future international relations.

9. How might cultural differences among nations influence the negotiation and drafting of treaties?

Answer: Cultural differences among nations play a critical role in the negotiation and drafting of treaties by shaping communication styles, negotiation tactics, and the interpretation of legal language. Different cultural backgrounds can lead to varying expectations regarding hierarchy, formality, and the value placed on consensus, which in turn affect how negotiations are conducted. For instance, cultures that prioritize collectivism may emphasize the importance of mutual benefits and long-term relationships, while those with individualistic tendencies might focus on protecting national interests and ensuring strict legal safeguards. These cultural factors can lead to diverse approaches in treaty formulation, where the language and structure of agreements are tailored to reflect the values and norms of the negotiating parties.

Furthermore, understanding cultural differences is essential for preventing misunderstandings and ensuring that treaties are interpreted consistently by all parties. Diplomats who are culturally aware can anticipate potential areas of conflict and work to harmonize differing perspectives through sensitive and inclusive negotiations. This cultural competence not only enhances the quality of treaty negotiations but also contributes to the durability and effectiveness of the resulting agreements, as they are more likely to be respected and upheld by all involved parties. In a globalized world, the ability to navigate cultural diversity is an invaluable asset in the pursuit of successful international diplomacy.

10. How can economic considerations be effectively integrated into treaty negotiations to ensure mutual benefits for all parties?

Answer: Economic considerations can be effectively integrated into treaty negotiations by incorporating detailed provisions that address trade, investment, intellectual property, and financial cooperation. These economic clauses are designed to create a framework that benefits all parties by promoting fair trade, reducing barriers to investment, and ensuring equitable access to markets. Negotiators use economic incentives and regulatory standards to balance competing interests, often employing quantitative models and economic forecasts to support their positions. By embedding clear, mutually beneficial economic terms into treaties, nations can foster stronger partnerships and build lasting alliances that enhance global prosperity and stability.

Moreover, effective integration of economic considerations requires a comprehensive approach that combines technical expertise with diplomatic negotiation. This may involve collaborative economic research, joint investment projects, and the establishment of dispute resolution mechanisms that address economic issues. By working together, nations can create a more predictable and stable economic environment, which in turn reinforces the overall success of diplomatic agreements. The careful balancing of economic interests within treaties is essential for ensuring that agreements are sustainable, resilient, and capable of adapting to changing global market conditions.

11. How might the inclusion of environmental and social clauses in treaties shape future international cooperation?

Answer: The inclusion of environmental and social clauses in treaties has the potential to shape future international cooperation by broadening the scope of diplomatic agreements to address critical global challenges such as climate change, human rights, and sustainable development. By incorporating provisions that mandate environmental protection, social justice, and equitable resource distribution, treaties can promote a more holistic approach to international relations that goes beyond traditional security and economic concerns. This integration encourages nations to collaborate on shared issues, fostering a sense of collective responsibility and paving the way for comprehensive frameworks that support global well-being.

Additionally, environmental and social clauses can serve as catalysts for innovative policy solutions that align with emerging global standards. As nations increasingly recognize the interdependence between economic development and environmental sustainability, such clauses can help to harmonize regulatory practices and incentivize responsible behavior. This approach not only enhances the legitimacy of international agreements but also contributes to a more stable and just global order. The long-term benefits of including environmental and social considerations in treaties are likely to become even more pronounced as the world faces the pressing challenges of the 21st century.

12. How might the evolution of international law influence the future negotiation processes of treaties?

Answer: The evolution of international law is expected to influence future treaty negotiation processes by providing a more standardized and predictable legal framework that guides state behavior and dispute resolution. As international legal norms continue to develop, they will shape the structure and content of treaties, ensuring that agreements are consistent with global principles such as human rights, environmental protection, and the rule of law. This evolution will likely lead to more rigorous negotiation protocols and the inclusion of binding enforcement mechanisms, which can enhance the credibility and durability of treaties. The progressive refinement of international law creates an environment where diplomatic negotiations are more transparent and accountable, reducing ambiguities and fostering trust among states.

Moreover, as international law becomes increasingly integrated into national legal systems, future treaty negotiations may involve greater collaboration between domestic and international legal experts. This convergence of legal traditions will require negotiators to be well-versed in both national and global legal standards, ensuring that treaties are crafted in a manner that is enforceable at multiple levels. The interplay between international legal evolution and diplomatic practice will shape the future of treaty negotiations, making them more adaptive, equitable, and responsive to the complex challenges of a globalized world.