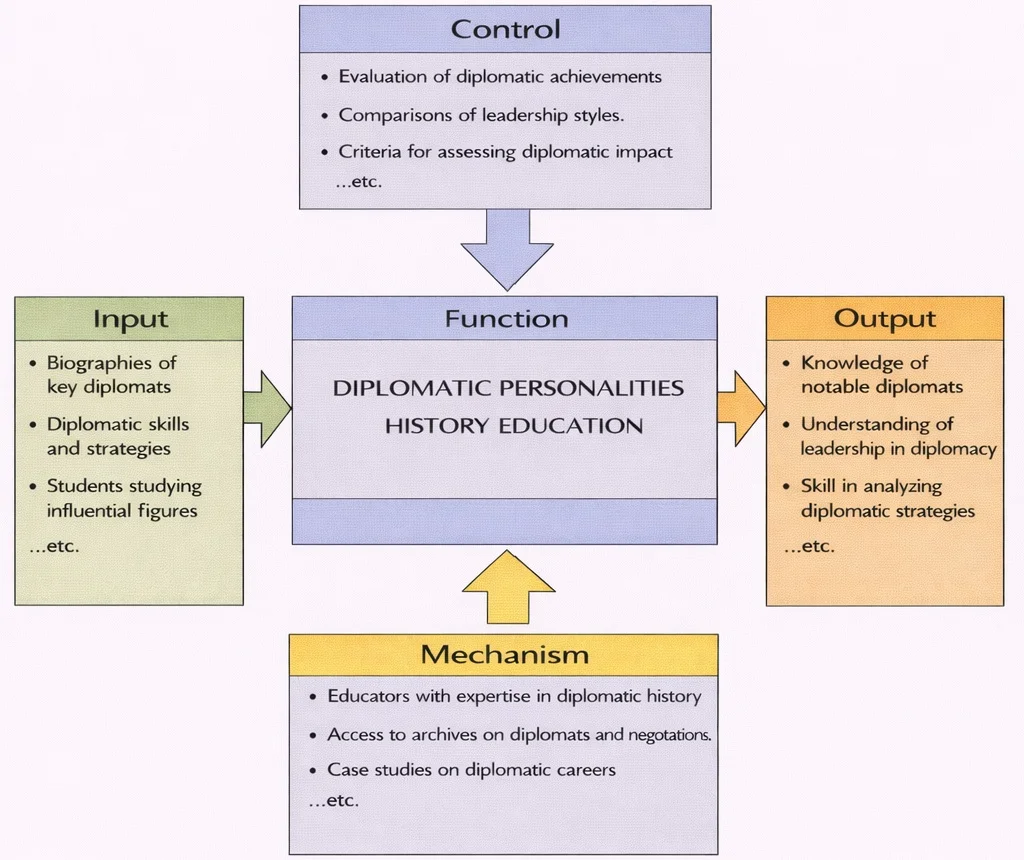

Diplomatic history can feel abstract until it is anchored in people—real individuals who negotiated under pressure, made choices with consequences, and carried ideals (and sometimes ambitions) into international arenas. Diplomatic Personalities History Education uses those lives as a “human lens” for understanding how diplomacy actually works.

As the diagram suggests, students begin with biographies, strategies, and key episodes as inputs, then interpret them through controls such as achievement evaluation and leadership comparisons. With mechanisms like expert teaching, archival resources, and carefully chosen career case studies, learners move beyond hero-worship or criticism and develop a disciplined way to judge influence: what a diplomat wanted, what constraints they faced, what tools they used, and what their decisions changed. The result is practical historical insight—knowledge of notable diplomats, a clearer grasp of leadership in diplomacy, and stronger analytical skill in reading diplomatic strategy across time.

Throughout history, individual diplomats have shaped the course of international affairs not only through policy but also through personality, conviction, and style. These diplomatic history makers—whether skilled negotiators, visionary leaders, or subtle persuaders—have been instrumental in forging alliances, averting wars, and crafting treaties. By studying their legacies, students gain insight into how individuals operate within complex systems to influence global change.

The evolution of global political thought and history of ideas provides the ideological background that shaped the strategic worldview of many prominent diplomats. These figures often operated within intellectual traditions born from the Enlightenment and modern constitutions or adapted them to new geopolitical realities. Their influence bridged the philosophical with the practical, offering continuity between theoretical principles and real-world applications.

Some diplomats became renowned through their role in economic statecraft. The stories of financial history and economic thought and theory illustrate how personalities could channel complex economic ideas into compelling diplomatic strategies. These efforts were not always conducted in calm times—many operated in the context of economic history of warfare and post-war reconstruction.

At times, the charisma or tenacity of diplomatic personalities became vital in maintaining alliances or in navigating periods of electoral volatility, as documented in electoral history and the challenges of electoral fraud and integrity. Understanding their role requires contextual awareness of history of political systems and the dynamics of electoral systems and political parties.

The cultural impact of these figures is equally significant. Many helped shape gender and cultural history through diplomatic representation, or influenced national identities via education history. Their influence extended well beyond treaties and state visits, inflecting how societies perceive and project themselves.

In synthesizing the contributions of these figures, students engage with the broader fabric of history. From environmental economic history to the nuances of economic diplomacy, diplomatic personalities embody intersections of the personal, political, and institutional. Their legacies are deeply embedded in history of political economy, economic history, and even the conduct of guerrilla warfare and insurgency studies.

This is a richly colored, poster-like illustration depicting a ceremonial diplomatic gathering inside a high-ceilinged hall. At the center, two senior statesmen in suits clasp hands in front of a radiant globe, suggesting an agreement or the forging of an alliance. Around them, rows of seated delegates confer at round tables covered with documents, microphones, and small desk flags. The composition is crowded but orderly, evoking the bustle of international negotiation.

Strong British and American motifs frame the scene: a Union Jack and the U.S. flag drape across the background; Big Ben rises at right; and a spread-winged eagle hovers near the top, reinforcing themes of power and state symbolism. The palette leans into saturated oranges, blues, and golds, giving the image a warm, heroic tone reminiscent of vintage propaganda art. Lighting highlights the central handshake while cooler shadows recede into the audience, guiding the viewer’s eye from agreement to assembly.

Overall, the illustration blends realism with idealization to convey diplomacy as spectacle: national emblems, the glowing globe, and confident body language emphasize unity, strategy, and the global stakes of high-level negotiations.

Table of Contents

The Role of Diplomatic Personalities

Definition and Importance

A diplomatic personality is an individual—head of government, foreign minister, envoy, negotiator, or non-state mediator—whose judgment, style, networks, and credibility measurably shape international outcomes. While structure and interests set the stage, distinctive people often decide the script’s turning points: they frame problems, build coalitions, choose timing, and absorb risk. Their influence is most visible at moments of uncertainty (crisis, transition, or breakthrough), when rules are thin and trust is scarce.

How Diplomatic Personalities Exercise Influence

- Agenda-setting & framing:

- Define the core problem (security, trade, climate) and the acceptable language for discussing it.

- Sequence issues to unlock movement—e.g., confidence-building first, hard sovereignty questions later.

- Coalition-building:

- Map stakeholders, align overlapping interests, and offer side-payments or guarantees to hold a majority together.

- Bridge across blocs (regional, ideological, or institutional) using trusted intermediaries and minilateral formats.

- Signaling & assurance:

- Use words, deadlines, and calibrated actions (sanctions relief, ceasefire pauses, troop postures) to convey resolve and respect.

- Deploy backchannels to reduce misperception while keeping public positions intact.

- Dealcraft:

- Design packages with reciprocity, verification, and reversibility so parties can move without maximum trust.

- Write “constructive ambiguity” where needed, while protecting core interests with annexes, snap-back clauses, or review cycles.

- Public diplomacy:

- Shape domestic and international narratives to generate consent and protect agreements from backlash.

- Engage media, diasporas, business, and civil society to broaden the constituency for peace or cooperation.

Core Attributes of Diplomatic Personalities

- Strategic Vision

- Connects day-to-day bargaining to a long-term end-state; anticipates second-order effects and exit ramps.

- Balances values and interests; knows when to bank incremental gains versus push for a grand bargain.

- Charisma & Persuasion

- Builds trust quickly; reads rooms and adapts tone—technical with experts, principled with publics, personal with leaders.

- Uses moral suasion and credibility (“reputation for keeping promises”) to lower others’ perceived risks.

- Resilience & Adaptability

- Absorbs shocks and retools strategy after setbacks; maintains composure under time pressure and media scrutiny.

- Shifts formats—bilateral, trilateral, shuttle diplomacy, or quiet retreats—when talks stall.

- Analytical & Emotional Intelligence

- Combines data literacy (maps, budgets, force posture, trade flows) with empathy for counterpart constraints.

- Detects red-lines, domestic veto players, and “win conditions” for all sides.

- Integrity & Reliability

- Signals clearly; honors confidentiality; separates private assurances from public theatrics.

- Anchors agreements in verifiable mechanisms to sustain trust beyond personalities.

Decision Toolkit: Methods Skilled Diplomats Use

- BATNA calculus: Continually reassess the Best Alternative To a Negotiated Agreement for all parties and improve it at home (alliances, aid, contingency plans).

- Issue-linkage: Trade across domains (security for economic concessions) to expand the bargaining space.

- Time management: Exploit windows (elections, summits, markets) and use deadlines without cornering counterparts.

- Verification design: Pair commitments with monitoring, phased implementation, and snap-backs to manage risk.

- Principled pragmatism: Hold firm on core norms (sovereignty, human rights) while being flexible on modalities and sequencing.

Constraints & Failure Modes

- Domestic politics: Legislatures, courts, militaries, or public opinion can veto deals; durable agreements need inclusive consultation and benefits at home.

- Asymmetries & misperception: Power gaps and clashing narratives can poison trust; unmanaged expectations trigger “agreement shock.”

- Over-personalization: Deals that rely solely on leader rapport may unravel without institutional anchors.

- Ethical drift: Secrecy and expediency can sideline rights; legitimacy requires transparency, oversight, and lawful mandates.

Measuring Impact

- Short-run: Ceasefires held, hostages released, sanctions calibrated, market volatility reduced, diplomatic channels reopened.

- Medium-run: Treaties ratified and implemented; trade, aid, or security cooperation increases; verification reports show compliance.

- Long-run: Conflict recurrence declines; regional institutions strengthen; norms diffuse; public approval and elite consensus stabilize.

Illustrative Archetypes (One-line Vignettes)

- The Architect: Designs frameworks others inhabit (e.g., creators of multilateral orders and regional unions).

- The Firefighter: Crisis manager who uses de-escalation and backchannels to avert war.

- The Bridge-Builder: Trusted go-between across ideological divides, converting private understanding into public agreements.

- The Merchant-Diplomat: Expands economic corridors and standards that lock in peace through interdependence.

- The Norm Entrepreneur: Elevates human rights, climate, or health security from rhetoric to binding rules.

Enduring Lesson

Institutions matter—and so do people. Diplomatic personalities cannot rewrite geography or interests, but at pivotal moments they can widen the possibility frontier: reframing choices, lowering risks, and converting fragile openings into durable peace and cooperation.

The Role of Diplomatic Personalities

Winston Churchill

- Role:

- Prime Minister of the United Kingdom during World War II (1940–1945; 1951–1955); wartime strategist, alliance-builder, and post-war statesman.

- Signature Episodes & Diplomatic Craft:

- Forging the Grand Alliance: Transformed Britain’s bilateral ties with the United States and the Soviet Union into a workable coalition despite ideology and personality clashes.

- Atlantic Charter (1941): With Franklin D. Roosevelt set principles—self-determination, free trade, collective security—that later informed the UN Charter.

- Personal diplomacy: Intensive correspondence with Roosevelt; strategic flattery and frankness with Stalin to keep the coalition intact during crises (e.g., Tehran, Yalta).

- War Aims & Messaging: Speeches (“Their Finest Hour,” “We shall fight on the beaches”) mobilized domestic resilience and signaled resolve to allies and adversaries.

- Managing Wartime Bargains: Accepted painful compromises (e.g., “percentages agreement” sketch with Stalin in 1944) to protect core British interests while sustaining unity.

- Forging the Grand Alliance: Transformed Britain’s bilateral ties with the United States and the Soviet Union into a workable coalition despite ideology and personality clashes.

- Methods & Style:

- Master of narrative framing; used symbolism, historical memory, and humor to bind coalitions.

- Preferred leader-to-leader channels, but relied on professional diplomats and military liaison missions for follow-through.

- Critiques & Constraints:

- Post-war limits of British power forced recalibration; some colonial policies drew criticism.

- Legacy:

- Helped shape the UN’s creation; his 1946 “Iron Curtain” speech alerted the West to the emerging Cold War; enduring model of crisis leadership fused with coalition diplomacy.

Henry Kissinger

- Role:

- U.S. National Security Advisor (1969–1975) and Secretary of State (1973–1977); chief architect of détente.

- Signature Episodes & Diplomatic Craft:

- U.S.–China Rapprochement:

- Secret 1971 trip via Pakistan; set the stage for Nixon’s 1972 visit and the Shanghai Communiqué—reshaping the global balance by triangulating with the USSR.

- Détente with the USSR:

- SALT I and the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty (1972); crisis management after the 1973 Arab–Israeli War to avoid superpower confrontation.

- Middle East Shuttle Diplomacy:

- Back-to-back flights among capitals after the Yom Kippur War produced disengagement agreements (Sinai I & II; Syrian front) that stabilized borders and enabled later peace.

- U.S.–China Rapprochement:

- Methods & Style:

- Realpolitik; secrecy and backchannels; issue linkage and sequencing; personalized relationships with leaders to unlock concessions.

- Critiques & Constraints:

- Support for authoritarian partners and covert actions drew enduring controversy; trade-offs between stability and human rights remain debated.

- Legacy:

- Reordered great-power geometry; institutionalized crisis de-escalation mechanisms; established the template for high-stakes shuttle diplomacy.

The image shows a close, indoor encounter between three pivotal figures of Cold War diplomacy. On the left, U.S. National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger, wearing a dark business suit, patterned tie, and heavy-rimmed glasses, listens attentively. In the center background, Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai stands composed in a gray Zhongshan (“Mao”) suit, hands lightly clasped, his gaze directed toward the speakers. On the right, Chairman Mao Zedong, also dressed in a gray Zhongshan suit, addresses Kissinger with his right index finger raised for emphasis, suggesting instruction or a key point in discussion. The warm, subdued lighting and dark wood backdrop give the scene a private, back-channel feel. The composition captures the careful choreography of the U.S.–China opening: Kissinger’s secret talks with Zhou culminated in meetings with Mao, paving the way for President Nixon’s 1972 visit and a strategic realignment in the Cold War.

Eleanor Roosevelt

- Role:

- U.S. First Lady (1933–1945); U.S. Delegate to the UN (1945–1952); Chair of the UN Commission on Human Rights.

- Signature Episodes & Diplomatic Craft:

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR, 1948):

- Chaired drafting committee; bridged philosophical and geopolitical divides to produce a concise, accessible text adopted by the General Assembly.

- Used inclusive language and pragmatic compromises (e.g., civil–political with social–economic rights) to build a broad coalition.

- Soft-Power Advocacy:

- Spoke directly to publics via press, radio, and travel; reframed rights as universal standards rather than Western impositions.

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR, 1948):

- Methods & Style:

- Empathy and moral suasion; painstaking consensus-building; meticulous chairing to keep negotiations moving.

- Legacy:

- Anchored human rights in the post-war order; the UDHR became the yardstick for later treaties and national constitutions.

The image is a warm, colorized photograph of Eleanor Roosevelt and Franklin D. Roosevelt seated side-by-side on wooden armchairs against a soft, out-of-focus backdrop of trees and late-summer light. Eleanor, on the left, wears a sleeveless white dress and matching headband; her posture is upright, hands gently clasped on her lap, her expression composed and attentive. Franklin, on the right, is dressed in a tailored gray three-piece suit with a patterned tie and a white pocket square. He faces the camera with a calm, confident smile, his left hand resting on the chair arm and his right hand relaxed across his knee. The scene conveys poise and partnership at a pivotal moment in 1932, shortly before FDR’s successful presidential campaign and the couple’s emergence as central figures in American and international affairs.

Otto von Bismarck

- Role:

- Minister-President of Prussia; first Chancellor of the German Empire (1871–1890); strategist of power politics and summitry.

- Signature Episodes & Diplomatic Craft:

- Unification & Aftercare: Orchestrated wars of limited aims (against Denmark, Austria, France) to unify Germany; then pivoted from warfare to alliance management to prevent encirclement.

- Congress of Berlin (1878):

- Acted as “honest broker” among great powers over the Balkans; recalibrated treaties to avoid a wider European war.

- Web of Treaties:

- Dreikaiserbund, Dual Alliance with Austria-Hungary, Reinsurance Treaty with Russia—flexible architecture to isolate France and dampen crises.

- Methods & Style:

- Cold arithmetic of interests; controlled leaks and staged summits; exploited timing and credible commitments.

- Legacy & Limits:

- Preserved continental stability for two decades; system proved fragile once successors abandoned his delicate balances, contributing to tensions before 1914.

The image shows a full-length bronze statue of Otto von Bismarck mounted on a multi-tiered plinth built from irregular blocks of reddish stone. Bismarck stands upright in a martial pose, facing forward. He wears a Pickelhaube spiked helmet, a military tunic, boots, and a heavy cloak that drapes over his shoulders. His right hand rests on the pommel of a long, sheathed sword that extends to the base; his left hand grips a strap attached to a leather dispatch case hanging at his hip, evoking the tools of 19th-century statecraft and war. The figure’s chest bears an order cross, and the cloak’s folds are deeply modeled. At the plinth’s front a bronze plaque reads “OTTO VON BISMARCK 1815–1898.” Surrounding the monument are leafy green trees beneath a pale, overcast sky, placing the monumental figure within a quiet park setting. The composition emphasizes Bismarck’s role as the architect of German unification and a symbol of Realpolitik, strength, and authority.

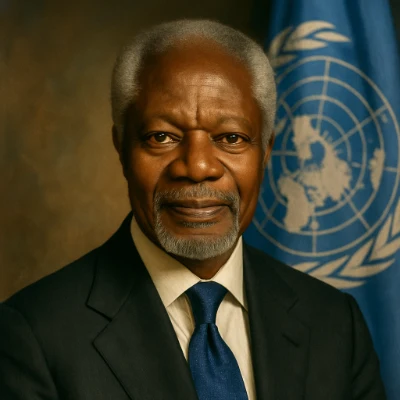

Kofi Annan

- Role:

- Secretary-General of the United Nations (1997–2006); Nobel Peace Prize (2001, shared with the UN).

- Signature Episodes & Diplomatic Craft:

- UN Reform & Accountability: Strengthened peacekeeping doctrine after failures in Rwanda/Srebrenica; pushed for clear mandates, rules of engagement, and rapid deployment.

- Responsibility to Protect (R2P): Advanced the principle that sovereignty entails responsibility; opened pathways for protecting civilians when states fail.

- Millennium Development Goals (MDGs): Built a unifying global agenda around measurable poverty reduction; mobilized donors, governments, and civil society.

- Quiet Mediation: Engaged in the Balkans, Timor-Leste, and later (as elder statesman) in Syria and Kenya.

- Methods & Style:

- Calm, understated persuasion; coalition-building with member states and NGOs; emphasis on legitimacy and process.

- Challenges & Legacy:

- Faced criticism over Oil-for-Food oversight; nonetheless left stronger norms on civilian protection and a results-oriented development frame widely emulated.

The image is a head-and-shoulders portrait of Kofi Annan set against a warm, neutral backdrop with the blue UN flag on the right side of the frame. Annan faces the camera with a calm expression, his silver hair and neatly trimmed beard framing a composed smile. He wears a dark business suit, white shirt, and deep blue silk tie. The UN emblem on the flag—an azimuthal world map encircled by olive branches—subtly anchors the setting in multilateral diplomacy. The lighting is soft and even, highlighting the contours of his face and conveying a dignified, official tone appropriate to an institutional portrait of a UN Secretary-General.

Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord

- Role:

- French foreign minister and statesman under multiple regimes (Revolution, Napoleon, Bourbon Restoration); master negotiator at the Congress of Vienna (1814–1815).

- Signature Episodes & Diplomatic Craft:

- Congress of Vienna:

- Secured France’s rapid rehabilitation after Napoleon by championing the “principle of legitimacy”; prevented punitive dismemberment and restored France as a balancing power.

- Balancing Great Powers:

- Played Britain, Austria, Prussia, and Russia against one another to defend French interests while presenting himself as guardian of European equilibrium.

- Congress of Vienna:

- Methods & Style:

- Elegant ambiguity; patience; leveraging personal networks; making moderation appear virtuous and in others’ self-interest.

- Legacy:

- Helped craft a settlement that kept great-power war at bay for nearly a century; a case study in how diplomatic credibility can outlast regime change.

The image presents a dignified, full-length oil-style portrait of Talleyrand. He stands slightly turned toward the viewer’s left, his gaze steady and composed. He wears an early-19th-century ensemble: dark green frock coat, waistcoat, knee breeches, white stockings, buckled shoes, and a high white cravat. A small red decoration (order ribbon) is pinned to his lapel. Talleyrand’s right hand rests on a slender walking cane; his left hand holds a black bicorne hat at his side. The setting is a shadowed, neoclassical room. On the left background stands a marble bust atop a square pedestal; a second bust appears on a matching pedestal at the far right, framing the figure. A blue-upholstered, gilded side chair sits to Talleyrand’s right, its curved back and carved legs catching the warm light. The palette is muted—olive, umber, and gold—evoking the measured elegance and calculated poise associated with Talleyrand’s diplomatic career.

Zhou Enlai

- Role:

- Premier and Foreign Minister of the People’s Republic of China; chief architect of PRC diplomacy from 1949 through the 1970s.

- Signature Episodes & Diplomatic Craft:

- Bandung Conference (1955):

- Helped define the Non-Aligned/Asian–African solidarity agenda; introduced “Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence” (sovereignty, non-aggression, non-interference, equality, mutual benefit).

- Opening to the United States:

- Hosted secret talks with Kissinger (1971); choreographed Nixon’s 1972 visit; managed symbolism and protocol to signal strategic reorientation.

- Border & Crisis Management:

- Negotiated ceasefires and stabilized delicate relationships (e.g., with India and the USSR at various junctures) through disciplined messaging and incrementalism.

- Bandung Conference (1955):

- Methods & Style:

- Courteous, precise, pragmatic; used hospitality, meticulous protocol, and careful wording to reduce mistrust while protecting core interests.

- Legacy:

- Positioned China within a global diplomatic network and paved the way for its normalization with the West.

A formal, studio-style oil portrait shows Zhou Enlai from the chest up. He wears a buttoned dark Zhongshan (Mao) suit with two chest pockets and a small red lapel pin. His head is turned a touch to the viewer’s left, eyes focused and alert, mouth set in a composed line. Zhou’s hair is swept back neatly, revealing strong brows and high cheekbones that catch soft, directional light. The background is a muted, textured brown that places full emphasis on the sitter’s face and uniform. The restrained color palette and smooth brushwork convey dignity, discipline, and the quiet authority associated with Zhou’s role in Chinese statecraft and landmark diplomatic initiatives, including rapprochement with the United States and mediation in early post-colonial Asia.

Dag Hammarskjöld

- Role:

- Secretary-General of the United Nations (1953–1961); pioneer of UN peacekeeping and impartial crisis mediation.

- Signature Episodes & Diplomatic Craft:

- Suez Crisis (1956):

- Worked with member states to create the first UN Emergency Force (UNEF), separating combatants and establishing a model for future peacekeeping missions.

- Congo Crisis (1960–1961):

- Asserted UN autonomy against great-power pressure; used airlifts, field missions, and direct talks to prevent wider war (perished in a plane crash while on a mission).

- Suez Crisis (1956):

- Methods & Style:

- Quiet, principled diplomacy; defended the UN Charter’s impartiality; innovated operational tools (standby forces, Secretary-General “good offices”).

- Legacy:

- Defined the modern Secretary-General as an independent mediator; institutionalized peacekeeping as a core UN function.

This color portrait presents Dag Hammarskjöld—Swedish diplomat and the United Nations’ second Secretary-General (1953–1961)—sitting at a polished wooden desk. A large, muted world map fills the background, visually anchoring his global remit. Hammarskjöld wears a charcoal suit, light blue shirt, and dotted blue tie; his hands rest calmly around a fountain pen on a single sheet of paper, suggesting the careful, written craft of diplomacy. The image captures the qualities for which Hammarskjöld became renowned: discretion, moral seriousness, and quiet resolve. During his tenure he expanded UN peacekeeping, launching the first armed peacekeeping force during the Suez Crisis (1956) and later confronting the Congo Crisis (1960–61). His emphasis on an independent international civil service and “quiet diplomacy” reshaped the Secretary-General’s office into an active mediator rather than a merely administrative role. The contemplative expression and uncluttered composition echo his reputation as a philosopher-diplomat—author of Markings—whose approach blended legal precision with ethical reflection. The portrait invites viewers to associate the pen and map with his lifelong commitment to negotiated solutions in a rapidly decolonizing world.

Key Themes in the Study of Diplomatic Personalities

Leadership Styles

Diplomatic figures exhibit distinctive leadership approaches shaped by era, regime type, domestic coalitions, and personal temperament. Understanding these styles helps explain why similar problems yield different diplomatic outcomes.

- Collaborative Leaders

- Build broad coalitions, delegate effectively, and prefer multilateral venues.

- Tools: summitry, alliance management, confidence-building measures (CBMs), and inclusive negotiation formats.

- Example: Franklin D. Roosevelt’s coalition-crafting with Churchill and Stalin, culminating in the Atlantic Charter and later the United Nations framework.

- Strategic Realists

- Prioritize power balances, sequencing, and trade-offs; accept imperfect agreements to lock in advantages.

- Tools: back-channels, triangular diplomacy, linkage, and step-by-step accords.

- Example: Henry Kissinger’s Realpolitik—detente with the USSR, rapprochement with China, and shuttle diplomacy in the Middle East.

- Norm Entrepreneurs

- Reframe interests as shared values, embedding new rules into international institutions.

- Tools: declarations, drafting committees, soft-law instruments, and public advocacy.

- Example: Eleanor Roosevelt guiding the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and normalizing a global rights vocabulary.

- Stabilizers/Conservators

- Seek equilibrium through intricate treaty webs and cautious risk management.

- Tools: secret protocols, non-aggression pacts, and balanced alliance systems.

- Example: Otto von Bismarck’s post-1871 alliance architecture to contain rivalry and isolate flashpoints.

- Moral Persuaders

- Lead by ethical argument and example, elevating legitimacy as a source of influence.

- Tools: UN platforms, independent mediation mandates, and transparency.

- Example: Dag Hammarskjöld’s “quiet diplomacy” and the creation of impartial UN peacekeeping norms.

- Network Brokers

- Operate across states, NGOs, media, and business to unlock complex, multi-stakeholder deals.

- Tools: track-two dialogues, public–private partnerships, and issue-linkage across domains.

- Example: Kofi Annan’s coalition building around the Millennium Development Goals and Responsibility to Protect debates.

Crisis Management

Diplomatic personalities are defined by how they perceive, prioritize, and sequence actions under acute time pressure. Effective crisis leadership blends signaling, controlled escalation, and credible off-ramps.

- Sense-Making & Framing

- Rapidly assemble intelligence, challenge assumptions, and define objectives that partners can accept.

- Example: Winston Churchill’s framing of 1940 as a civilizational struggle, aligning British society and allies behind endurance.

- Escalation Control

- Use credible but limited military or economic signals paired with private assurances.

- Example: Kennedy–Khrushchev crisis management (1962): naval quarantine plus back-channel letters to trade concessions.

- Process Design

- Choose venues (shuttle talks, secret channels, summits) that reduce domestic and international spoilers.

- Example: Shuttle diplomacy after the Yom Kippur War—sequenced disengagements before comprehensive talks.

- Coalition & Public Management

- Coordinate allies, manage parliamentary support, and shape public narratives to sustain negotiating space.

- Example: Churchill and FDR’s joint messaging (speeches, communiqués) to keep wartime publics aligned.

- Exit Strategies & Guarantees

- Lock in compliance via verification, phased timetables, peacekeeping, or economic sweeteners.

- Example: UN peacekeeping under Hammarskjöld institutionalized neutral monitoring as a credible exit mechanism.

- Typical Failure Modes

- Mirror-imaging adversaries; overpromising; domestic veto players; signaling that is too ambiguous or too provocative.

Legacy and Influence

Legacies endure when personalities translate momentary leverage into rules, institutions, and durable narratives. Scholars assess influence across norms, institutions, and strategic geography.

- Institutionalization

- Embedding practices into standing bodies or treaties ensures continuity beyond individual tenure.

- Example: Eleanor Roosevelt’s human-rights architecture and the ongoing UN treaty system.

- Norm Diffusion

- Ideas travel through teaching, model agreements, and elite socialization.

- Example: Kofi Annan’s stewardship of the MDGs mainstreamed measurable development targets worldwide.

- Strategic Cartography

- Alliance maps, buffer zones, and CBMs reshape regional security orders.

- Example: Bismarck’s alliance web defined Europe’s late-19th-century balance, long outlasting his chancellorship.

- Reputational Narratives

- Speeches, memoirs, and iconic images generate durable public memory that frames future policy debates.

- Example: Churchill’s wartime oratory and post-war “Iron Curtain” speech anchoring early Cold War discourse.

- Assessment Metrics

- Short-term: de-escalation, ceasefires, crisis cost containment.

- Medium-term: treaty durability, compliance rates, alliance cohesion.

- Long-term: institutional survival, norm internalization, conflict-recurrence reduction.

Analytical Lenses for Students

- Personality & Psychology: cognition, risk tolerance, and belief systems.

- Domestic Politics: party coalitions, bureaucratic rivalry, media ecosystems.

- International Structure: polarity, technology shifts, and economic interdependence.

- Ethics & Law: legitimacy, human rights, and the justifications of means and ends.

Challenges in Diplomatic Leadership

Balancing National and Global Interests

Effective diplomats must advance domestic priorities while sustaining regional and global stability. Getting this balance wrong can erode alliances, trigger counter-coalitions, or undermine legitimacy.

- Inherent Tension: Domestic constituencies reward visible gains (trade access, security guarantees), while global forums prize compromise and rules.

- Policy Instruments: issue-linkage (trade-for-security), side-payments, phased timetables, and confidence-building measures (CBMs).

- Risks: overreach, moral hazard (allies free-ride), and “dual audience” mis-signaling to foreign and home publics.

- Case Lens—Bismarck: His post-1871 alliance web stabilized Europe but was criticized for centering German primacy; once the web unraveled, insecurity resurfaced.

- Mitigation Playbook: publish clear red lines, use independent verification, tie concessions to measurable compliance, and socialize choices through multilateral bodies.

Public Perception, Legitimacy, and Accountability

Diplomats operate under intense scrutiny from voters, parliaments, media, and history. Perceived secrecy or ethical trade-offs can delegitimize otherwise stabilizing deals.

- Competing Narratives: National honor vs. pragmatic compromise; short-term costs vs. long-term security.

- Information Disorder: Leaks, disinformation, and deepfakes can derail negotiations or harden positions.

- Case Lens—Kissinger: Strategic openings (China, détente) coexisted with controversial covert actions; legacy remains polarizing.

- Mitigation Playbook: strategic transparency (what/why now), democratic oversight in closed session, proactive myth-busting, and ethics impact statements for major agreements.

Adapting to Rapidly Changing Contexts

Geopolitics, technology, and transnational threats evolve faster than traditional diplomatic cycles. Leaders must refresh mandates and toolkits without losing strategic coherence.

- Shifting Threats: pandemics, cyber intrusions, AI-accelerated influence ops, climate insecurity, and supply-chain shocks.

- Complex Actors: great powers, middle powers, city networks, multinationals, and civil society—often with veto power.

- Case Lens—Kofi Annan: Reframed post-Cold-War diplomacy around human security, development metrics (MDGs), and responsibility to protect.

- Mitigation Playbook: horizon scanning units, red-team exercises, cross-sector task forces, and agile “minilateral” formats that can scale to the UN/EU frameworks.

Domestic Constraints and Coalition Management

Even well-designed international bargains can fail at home due to partisan polarization, bureaucratic rivalry, or judicial review.

- Pitfalls: two-level game deadlock, spoiler ministries, and electoral calendars that shorten time horizons.

- Tools: prenegotiation consultations with legislators, inclusive delegations, sunset clauses, and pilot phases to build trust.

- Signal: pair external concessions with domestic safeguards (verification, snap-back clauses) to broaden support.

Ethical Trade-offs and Use of Leverage

Sanctions, arms sales, and security guarantees can deter aggression but also produce humanitarian or reputational costs.

- Assessment Questions: proportionality, civilian impact, exit criteria, and post-agreement justice.

- Better Practice: targeted sanctions, humanitarian carve-outs, independent monitoring, and time-bound authorities with review.

Secrecy vs. Transparency

Back-channels enable breakthroughs; transparency sustains legitimacy. Leaders must calibrate both.

- Guideline: keep talks discreet; keep goals, constraints, and guardrails public.

- Mechanisms: phased disclosure, parliamentary briefings, and declassification schedules after deals conclude.

Applications of Studying Diplomatic Personalities

Conflict Resolution

Close study of master negotiators yields portable methods for de-escalation, designing ceasefires, and crafting durable settlements.

- Toolkits to Imitate: pre-talks confidence building, issue-linkage, face-saving formulas, sequencing (easy wins → core issues), and verification regimes.

- Case Lens—Shuttle Diplomacy: Henry Kissinger’s shuttle diplomacy after the 1973 war pioneered mediated step-by-step disengagement agreements that are still used to separate forces and reduce miscalculation.

- Case Lens—UN Mediation: Kofi Annan’s emphasis on “single negotiating text,” humanitarian access, and regional guarantors informs modern ceasefire design from Africa to the Middle East.

- Design Heuristics: define red lines early; pair concessions with verification; lock in third-party monitors; build domestic buy-in before signature.

Leadership Training

Diplomatic biographies are living case studies for executive education, foreign service academies, and corporate leadership programs.

- Skills to Practice: BATNA analysis, coalition management, narrative framing, crisis decision-making under uncertainty, and intercultural fluency.

- Role Models: Winston Churchill (morale building and strategic communication), Zhou Enlai (listening diplomacy and incrementalism), Eleanor Roosevelt (values-based persuasion and norm entrepreneurship).

- Pedagogy: simulation exercises (back-channels, summits), red-team drills, and reflective memos that translate historical choices into modern playbooks.

Policy Design and Diplomacy Craft

Understanding how past figures structured alliances and treaties helps today’s officials engineer workable, monitorable agreements.

- From Bismarck to Today: balance-of-power insights for minilateral groupings, burden-sharing formulas, and escalation control clauses.

- Human-Rights Mainstreaming: Eleanor Roosevelt’s UDHR legacy informs rights clauses, ombudspersons, and review mechanisms in trade and security compacts.

- Implementation: road-maps with milestones, snap-back provisions, joint commissions, and public scorecards to maintain legitimacy.

Public Diplomacy and Strategic Communication

Iconic communicators demonstrate how to build mandate at home while signaling resolve abroad.

- What to Emulate: plain-language framing, storyline consistency across audiences, and “explainers” that show costs, benefits, and safeguards.

- Examples: Churchill’s wartime broadcasts; Annan’s human-security narrative; Roosevelt’s human-rights outreach.

Crisis Management and Early Warning

Patterns from historical crises help practitioners install playbooks before emergencies hit.

- Reusable Modules: hotlines, deconfliction protocols, incident-at-sea rules, and third-party fact-finding missions.

- Practice: table-top exercises that replicate leader choices and time pressure (e.g., “ExComm-style” formats).

Education, Research, and Civic Literacy

Biographies of diplomats anchor curricula in history, IR, law, and ethics—and cultivate informed citizens.

- Curricular Uses: seminar debates on ethics vs. raison d’état; archival projects that compare memos, speeches, and outcomes.

- Learning Outcomes: source evaluation, empathy across cultures, and applied reasoning about trade-offs.

Beyond Statecraft: Business, NGOs, and City Diplomacy

The same negotiation and coalition-building skills translate to corporate deals, humanitarian corridors, and climate alliances among cities.

- Applications: cross-sector compacts, supply-chain peace clauses, philanthropy-state coordination, and subnational climate pacts.

Why Study Diplomatic Personalities

Understanding the Human Dimension of International Relations

Exploring the Qualities That Define Effective Diplomats

- Strategic patience—sequencing small steps to unlock larger deals.

- Empathic listening—understanding the other side’s real constraints and domestic politics.

- Message discipline—clear, consistent signals that build trust and reduce miscalculation.

- Ethical reasoning—weighing national interest against human-rights principles and global norms.

- Intercultural fluency—language, protocol, and symbolism used to open doors rather than close them.

Analyzing the Impact of Personality on Crisis and Cooperation

- Backchannels & trust: leaders with reliable private lines de-escalate faster.

- Framing & narrative: persuasive storytellers can turn costly compromises into shared victories.

- Credibility under pressure: a record of keeping promises makes difficult concessions possible.

Recognizing How Identity, Background, and Beliefs Shape Diplomacy

Preparing for Careers in International Service and Global Leadership

- Negotiation & mediation skills (BATNA analysis, agenda-setting, issue linkage).

- Crisis decision-making under time pressure and imperfect information.

- Public communication—explaining complex trade-offs to domestic and international audiences.

- Ethical leadership—recognizing red lines and designing accountability mechanisms.

How to Study Diplomatic Personalities: Practical Assignments

- Case labs: reconstruct a high-stakes negotiation from memoirs, cables, and press briefings.

- Role-play simulations: practice summitry, back-channel messaging, and crisis pressers.

- Comparative profiles: contrast two diplomats facing similar problems; explain divergent outcomes.

- Ethics memo: evaluate a controversial decision and propose an alternative that preserves credibility and outcomes.

Key Takeaways

- Personality is not a replacement for power or interests—but it is often the decisive multiplier.

- Durable agreements emerge when technical craft is paired with trust, empathy, and principled restraint.

- Studying diplomats equips students to lead in any cross-cultural, high-stakes environment—not only in foreign affairs.

Diplomatic Personalities: Conclusion

Diplomacy is ultimately practiced by people. Institutions, treaties, and power balances create the stage, but it is the judgment, credibility, and moral imagination of individual diplomats that often determine whether states drift into conflict or move toward cooperation. From Winston Churchill’s alliance-building in existential war, to Eleanor Roosevelt’s elevation of universal human rights, to Henry Kissinger’s crisis management and strategic linkage, distinctive personalities have widened the range of what was politically and strategically possible in their time.

Studying these figures yields practical lessons that travel across eras:

- Strategy with sequencing: durable outcomes emerge from phased, verifiable steps—confidence-building first, core issues next.

- Coalitions over transactions: successful leaders convert one-off deals into frameworks that align allies, publics, and institutions.

- Principled pragmatism: values and interests need not be opposites; credible red lines and humane guardrails reinforce legitimacy.

- Communication as statecraft: clear narratives lower misperception, sustain domestic consent, and reassure adversaries about intent.

- Institutionalization: agreements outlast personalities when they are embedded in rules, monitoring, and shared benefits.

The risks are equally instructive: over-personalizing policy, ignoring domestic veto players, or privileging secrecy over legitimacy can unravel even elegant bargains. The most effective diplomats pair tactical agility with ethical restraint and ensure that their breakthroughs are anchored in institutions strong enough to survive leadership change.

In an era of intertwined crises—strategic rivalry, technological disruption, climate risk, and information disorder—the human element of diplomacy matters more, not less. Understanding how exceptional personalities navigated uncertainty equips students and practitioners to design agreements that are not only clever, but credible, inclusive, and durable. That is the enduring legacy of diplomatic personalities: expanding the possibility frontier for peace and cooperation when the stakes are highest.

Frequently Asked Questions – Diplomatic Personalities

What is meant by 'diplomatic personalities' in the study of diplomatic history?

'Diplomatic personalities' refers to individual diplomats, envoys, ambassadors, and negotiators whose decisions, character, background, and actions significantly influenced international relations, treaties, alliances, and diplomatic outcomes across history.

Why study diplomatic personalities instead of focusing only on states or treaties?

Studying diplomatic personalities helps reveal how individual choices, personal networks, leadership styles, and human judgment shaped international events. It complements structural analyses by highlighting contingency, negotiation skills, personal biases, and the impact of character on diplomacy.

What kinds of figures are typically considered diplomatic personalities?

Typical figures include long-serving ambassadors, special envoys, foreign ministers turned statesmen, negotiators of major treaties, consular officials, and even political leaders whose personal diplomacy — through correspondence, negotiation, or informal contact — affected international relations.

How do personal background and education influence a diplomat’s effectiveness?

A diplomat's upbringing, language skills, cultural literacy, education, social networks, and previous experience shape how they perceive other states, communicate, build trust, and negotiate. These personal attributes often affect their ability to interpret foreign contexts, build rapport, and make strategic decisions.

What role does personality and soft skills play in diplomatic negotiations?

Soft skills — such as empathy, communication, discretion, patience, and cultural sensitivity — often determine success in negotiation, mediation, crisis management, and long-term relationship building. Diplomatic personalities with strong interpersonal skills can open dialogue, defuse tensions, and create alliances beyond formal agreements.

How have diplomatic personalities shaped key historical treaties and alliances?

Throughout history, individual diplomats have played central roles in forging peace treaties, alliances, trade agreements, and territorial settlements. Their personal relationships, persuasion, and strategic foresight sometimes determined whether negotiations succeeded or failed, and whether agreements held or collapsed.

What challenges do historians face when studying diplomatic personalities?

Challenges include biased or incomplete sources (e.g., personal letters, memoirs), difficulty separating personal influence from structural factors, and the problem of hindsight bias. Historians must critically assess sources to avoid overemphasising individual agency at the expense of broader social, political, and economic forces.

How can diplomatic personalities help explain unexpected diplomatic outcomes or failures?

When structural analyses cannot fully account for surprising successes or failures of diplomacy, examining the decisions, misjudgments, or personality traits of key individuals can shed light on why negotiations derailed, why trust broke down, or why certain opportunities were seized or missed.

What skills do students and researchers develop by studying diplomatic personalities?

Students and researchers gain skills in prosopography, close reading of personal and diplomatic correspondence, contextualizing individual biographies, assessing influence and networks, and integrating individual-level analysis with broader historical and structural frameworks.

How does study of diplomatic personalities connect with social, cultural, and political history?

Diplomatic personalities serve as bridges between states, societies, and cultures. Their backgrounds, beliefs, and values often reflect social and cultural contexts; their choices are shaped by political institutions and pressures. Studying them enriches understanding of how diplomacy interacts with domestic politics and social norms.

Can studying diplomatic personalities inform contemporary diplomacy and international relations?

Yes — by learning how past diplomats navigated crises, built trust, and negotiated complex issues, policymakers and practitioners can draw lessons about negotiation, cross-cultural engagement, personality-driven diplomacy, and the human dimension of international relations.

How can this Diplomatic Personalities page be used with other resources on diplomacy in Prep4Uni?

Learners can combine this page with resources on diplomatic history, cultural diplomacy, treaty studies, international law, and global history. Studying biographies alongside institutional and structural perspectives helps provide a more holistic understanding of how diplomacy — person, practice, and policy — shaped world history.

Diplomatic Personalities: Review Questions and Answers:

1. What are diplomatic personalities and why are they significant in international relations?

Answer: Diplomatic personalities refer to influential individuals who have played key roles in shaping international relations through their unique skills, leadership, and negotiation abilities. These figures are significant because they have often bridged cultural, political, and ideological divides, enabling peaceful resolutions to conflicts and the forging of international alliances. Their personal charisma and adept communication skills have frequently been instrumental in advancing diplomatic initiatives and influencing policy decisions. Understanding their contributions helps us appreciate the human element in diplomacy and the impact that individual agency can have on global affairs.

2. How have personal qualities contributed to the success of diplomatic leaders?

Answer: Personal qualities such as charisma, empathy, resilience, and strong communication skills have greatly contributed to the success of diplomatic leaders. These attributes enable diplomats to build trust, forge relationships, and negotiate effectively even in high-stress situations. Their ability to listen and understand diverse perspectives often allows them to find common ground and craft solutions that satisfy multiple parties. As a result, these personal traits have been critical in overcoming political obstacles and achieving lasting agreements in international diplomacy.

3. In what ways have historical diplomatic figures influenced modern negotiation practices?

Answer: Historical diplomatic figures have influenced modern negotiation practices by establishing models of effective communication, strategic compromise, and ethical leadership. Their approaches to conflict resolution, characterized by patience, creativity, and a deep understanding of cultural nuances, have been studied and emulated by contemporary negotiators. By examining the tactics and methods used by these figures, modern diplomats gain valuable insights into handling complex negotiations and managing international crises. This legacy continues to shape training programs and diplomatic protocols around the world, ensuring that time-tested strategies are adapted to meet current challenges.

4. How do diplomatic personalities impact the development of international policies and treaties?

Answer: Diplomatic personalities impact the development of international policies and treaties through their ability to articulate national interests and negotiate favorable terms in multilateral settings. Their persuasive skills and deep understanding of both domestic and international issues enable them to craft policies that balance diverse interests and foster cooperation. Through effective negotiation, these individuals often play a decisive role in drafting treaties that have long-lasting implications for global governance. Their personal influence not only shapes the outcomes of negotiations but also helps to build trust among nations, which is essential for the successful implementation of international agreements.

5. What challenges do diplomats face when their personal styles clash with institutional constraints?

Answer: Diplomats often face challenges when their personal styles and innovative approaches clash with the rigid procedures and bureaucratic constraints of their institutions. Such clashes can hinder swift decision-making and reduce the effectiveness of diplomatic initiatives. The tension between individual initiative and institutional protocol requires diplomats to navigate complex internal dynamics while still pursuing creative solutions in international negotiations. Overcoming these challenges often involves balancing personal diplomacy with adherence to established norms, thereby ensuring that individual contributions complement rather than conflict with institutional objectives.

6. How have changes in global politics influenced the role of individual diplomats over time?

Answer: Changes in global politics have significantly influenced the role of individual diplomats by shifting the focus from traditional state-to-state interactions to more complex multilateral and transnational engagements. As globalization and technological advancements have transformed international relations, the personal impact of diplomats has become even more critical in navigating diverse and rapidly changing environments. Modern diplomats are required to be adept in cross-cultural communication and to manage a wider array of issues, from cybersecurity to environmental policy. These evolving responsibilities highlight the enduring importance of personal diplomacy in shaping effective global leadership.

7. How can the study of diplomatic personalities contribute to our understanding of international conflict resolution?

Answer: The study of diplomatic personalities contributes to our understanding of international conflict resolution by highlighting the personal strategies and negotiation tactics that have led to successful peace agreements. Through detailed case studies, we learn how individual diplomats have managed to de-escalate tensions, build consensus, and create lasting frameworks for cooperation. Their approaches often emphasize empathy, strategic compromise, and the ability to listen to conflicting parties. These insights provide valuable lessons for contemporary conflict resolution efforts and help to illustrate the pivotal role that personal leadership plays in achieving diplomatic success.

8. What role does cultural sensitivity play in the effectiveness of diplomatic negotiations?

Answer: Cultural sensitivity plays a crucial role in the effectiveness of diplomatic negotiations by enabling diplomats to understand and respect the diverse values, customs, and perspectives of the parties involved. This sensitivity helps to build trust and facilitate communication, making it easier to bridge ideological and cultural divides. Diplomatic personalities who exhibit cultural awareness are often better able to negotiate terms that are acceptable to all sides, thereby reducing the risk of misunderstandings and conflict. In a globalized world, the ability to navigate cultural differences is essential for achieving peaceful and productive international relations.

9. How have diplomatic personalities adapted their strategies in response to changing geopolitical landscapes?

Answer: Diplomatic personalities have adapted their strategies in response to changing geopolitical landscapes by continuously evolving their negotiation techniques and approaches to conflict resolution. Historical figures often had to modify their tactics to address new threats, alliances, and political contexts, demonstrating flexibility and innovation. Modern diplomats similarly adjust to the challenges posed by globalization, technological change, and shifting power dynamics among nations. Their ability to adapt is crucial for maintaining relevance and effectiveness in an ever-changing international environment, ensuring that diplomacy remains a dynamic tool for peace and cooperation.

10. How do individual diplomats balance national interests with the need for international cooperation?

Answer: Individual diplomats balance national interests with the need for international cooperation by employing negotiation strategies that seek mutually beneficial outcomes while safeguarding their country’s priorities. They use their personal influence and diplomatic skills to build consensus and foster trust among international partners, often engaging in creative problem-solving to reconcile conflicting interests. This balancing act requires a deep understanding of both domestic and global issues, as well as the ability to communicate effectively across cultural and political divides. By maintaining a pragmatic and flexible approach, successful diplomats can secure agreements that contribute to both national prosperity and global stability.

Diplomatic Personalities: Thought-Provoking Questions and Answers:

1. How might emerging digital communication technologies reshape the role of diplomatic personalities in international negotiations?

Answer: Emerging digital communication technologies are poised to transform the role of diplomatic personalities by enhancing their ability to engage with global audiences and manage negotiations in real time. Tools such as secure messaging apps, virtual conferencing platforms, and social media enable diplomats to bypass traditional channels and reach a wider audience with unprecedented speed and transparency. This shift can democratize the negotiation process, making it more participatory and inclusive, while also allowing diplomats to adapt swiftly to changing circumstances on the international stage. By leveraging these technologies, modern diplomats can maintain continuous dialogue with both state and non-state actors, thereby strengthening international relationships and enhancing the effectiveness of diplomatic initiatives.

In addition, digital communication technologies facilitate the collection and analysis of real-time data, which can inform more strategic decision-making. Advanced analytics and artificial intelligence can help diplomats predict trends and potential points of conflict, enabling proactive engagement before issues escalate. However, this increased reliance on digital platforms also raises challenges such as cybersecurity risks, data privacy concerns, and the potential for information manipulation. As diplomatic practices evolve, balancing technological advantages with these risks will be crucial for ensuring that digital tools contribute positively to international relations.

2. In what ways can historical diplomatic successes be leveraged to improve conflict resolution strategies today?

Answer: Historical diplomatic successes provide a rich repository of strategies that can be leveraged to improve conflict resolution efforts in today’s complex international environment. Past successes, such as landmark treaties and multilateral negotiations, offer valuable lessons on the importance of compromise, trust-building, and clear communication. These historical examples demonstrate how carefully crafted diplomatic initiatives can resolve disputes and prevent conflicts by addressing the underlying causes of tension and fostering mutual understanding. By studying these cases, modern diplomats can identify best practices and innovative approaches that have proven effective in achieving lasting peace, even in the most challenging circumstances.

Moreover, the lessons from historical diplomacy underscore the importance of patience and persistence in negotiations. Modern conflict resolution strategies can benefit from these insights by incorporating phased approaches that allow for gradual confidence-building and incremental progress. In addition, integrating historical perspectives into diplomatic training programs can equip current negotiators with the tools to anticipate and overcome obstacles similar to those encountered in past diplomatic endeavors. Ultimately, by applying the wisdom gleaned from historical diplomatic successes, contemporary policymakers can enhance the resilience and effectiveness of conflict resolution strategies on a global scale.

3. How might cultural diplomacy evolve to address contemporary global challenges such as migration and climate change?

Answer: Cultural diplomacy is likely to evolve to address contemporary global challenges like migration and climate change by emphasizing shared human experiences and common goals. As migration becomes a pressing issue and climate change poses unprecedented threats to communities worldwide, cultural diplomacy can serve as a platform for fostering dialogue, empathy, and collaboration across borders. Initiatives such as international cultural festivals, collaborative art projects, and cross-cultural educational exchanges can help to build bridges between diverse communities, mitigating tensions and promoting understanding. These efforts can highlight the interconnectedness of global challenges, demonstrating that issues such as environmental degradation and human mobility require collective action.

Furthermore, cultural diplomacy can integrate modern digital tools to amplify its reach and impact. Virtual reality, social media, and online collaboration platforms can connect individuals from different parts of the world, facilitating real-time cultural exchanges and public discussions on critical issues. By adapting to the digital age, cultural diplomacy can offer innovative solutions that transcend traditional boundaries, ultimately contributing to more effective and inclusive global governance. This evolution is essential for addressing the multifaceted nature of contemporary challenges and ensuring that diplomatic efforts remain relevant and transformative in the modern era.

4. How might interdisciplinary research enhance our understanding of the personal qualities that define successful diplomats?

Answer: Interdisciplinary research can greatly enhance our understanding of the personal qualities that define successful diplomats by integrating insights from psychology, sociology, history, and political science. This comprehensive approach allows scholars to examine how traits such as empathy, resilience, adaptability, and effective communication contribute to diplomatic success. Psychological studies can provide quantitative data on personality traits and decision-making processes, while historical and sociological analyses offer context on how these qualities have been valued and cultivated in different eras and cultures. By synthesizing these diverse perspectives, researchers can develop a nuanced profile of the characteristics that enable diplomats to navigate complex international negotiations and build lasting relationships.

Moreover, interdisciplinary research can explore the impact of cultural and environmental factors on diplomatic behavior, shedding light on how personal qualities are shaped by both individual experiences and broader societal influences. This holistic perspective not only enriches academic understanding but also has practical implications for diplomatic training and recruitment. By identifying the key traits that correlate with successful diplomatic outcomes, institutions can tailor their programs to foster these qualities in future diplomats, ultimately enhancing the effectiveness of international relations and conflict resolution efforts.

5. How might historical diplomatic personalities inform modern leadership in a rapidly changing global environment?

Answer: Historical diplomatic personalities offer a wealth of lessons for modern leadership by exemplifying the qualities and strategies that have successfully navigated complex international challenges. Figures from history who demonstrated vision, adaptability, and moral integrity provide models for contemporary leaders facing the pressures of globalization, technological change, and shifting geopolitical landscapes. These individuals often managed to balance national interests with international cooperation, creating lasting alliances and resolving conflicts through dialogue and compromise. Their approaches can inspire modern leaders to adopt a more holistic and forward-thinking perspective, ensuring that diplomatic efforts remain resilient and effective in a rapidly evolving world.

In addition, the study of historical diplomatic personalities reveals the importance of cultural sensitivity, empathy, and strategic innovation in achieving successful outcomes. Modern leaders can learn from these examples by incorporating a blend of traditional diplomatic skills with modern technological tools, thereby enhancing their ability to address diverse challenges. By drawing on the experiences and insights of past diplomats, current and future leaders can develop strategies that are both principled and pragmatic, ultimately fostering a more stable and cooperative international order. This historical perspective serves as a guide for navigating the complexities of modern global leadership while upholding timeless values of peace and mutual respect.

6. How might digital tools and data analytics transform the study of diplomatic personalities and their influence on international relations?

Answer: Digital tools and data analytics have the potential to transform the study of diplomatic personalities by providing new methodologies for analyzing large datasets, historical records, and biographical information. Through digital archives, social media analysis, and advanced data visualization techniques, researchers can identify patterns and correlations between personal qualities, negotiation strategies, and diplomatic outcomes. These technological advancements enable a more quantitative and objective assessment of how individual diplomats have influenced international relations over time. By leveraging these tools, scholars can uncover insights that were previously difficult to discern through traditional qualitative analysis alone.

Additionally, digital platforms allow for the integration of diverse sources of information, ranging from historical documents to contemporary media coverage, providing a more comprehensive view of a diplomat’s career and impact. This multifaceted approach can highlight the evolution of diplomatic practices and reveal the dynamic interplay between individual agency and broader political contexts. Ultimately, the use of digital tools and data analytics enriches the study of diplomatic personalities, offering innovative ways to understand their contributions to global diplomacy and informing strategies for cultivating effective leadership in the future.

7. How might the evolution of diplomatic negotiation techniques shape the future of international conflict resolution?

Answer: The evolution of diplomatic negotiation techniques is poised to shape the future of international conflict resolution by incorporating innovative strategies that address the complexities of modern disputes. Historical developments in negotiation, such as the shift from rigid, hierarchical bargaining to more flexible, interest-based dialogue, have demonstrated that successful conflict resolution often depends on empathy, creativity, and mutual understanding. In the future, these techniques may be further refined through the integration of digital tools, real-time data analytics, and cross-cultural communication strategies, enabling diplomats to craft more effective and adaptive solutions. This evolution can lead to more sustainable and inclusive peace agreements, as negotiators are better equipped to address the multifaceted nature of contemporary conflicts.

Moreover, the adoption of advanced negotiation techniques may transform the role of mediators, allowing them to serve as facilitators who harness technology to bridge divides between conflicting parties. The use of simulation tools and virtual negotiation platforms can create more interactive and engaging environments for dialogue, enhancing the ability to test and refine various conflict resolution strategies. By drawing on both historical lessons and modern technological advancements, the future of international conflict resolution is likely to be characterized by increased collaboration, greater transparency, and a more dynamic approach to diplomacy that prioritizes long-term stability over short-term gains.

8. How can lessons from past diplomatic negotiations help address the challenges of multilateralism in today’s globalized world?

Answer: Lessons from past diplomatic negotiations provide valuable insights into the challenges of multilateralism by illustrating effective strategies for managing complex, multi-party interactions. Historical examples, such as the negotiations leading to the Treaty of Versailles or the establishment of the United Nations, highlight the importance of balancing national interests with collective goals. These cases demonstrate that successful multilateral negotiations require transparency, trust-building, and the willingness to compromise, even when interests diverge significantly. By studying these examples, modern diplomats can develop frameworks for multilateral engagement that foster cooperation and address common challenges, such as climate change, economic inequality, and international security.

In addition, historical lessons emphasize the need for robust institutional mechanisms to support multilateralism, including clear rules, effective communication channels, and conflict resolution procedures. These institutional frameworks help to mitigate the complexities inherent in coordinating the actions of numerous states with differing priorities. By integrating best practices from the past into modern diplomatic processes, policymakers can enhance the effectiveness of multilateral organizations and ensure that global governance structures remain resilient in the face of evolving challenges. This approach not only strengthens international cooperation but also contributes to a more stable and interconnected global order.

9. How might cultural factors influence the effectiveness of diplomatic negotiations in diverse international contexts?

Answer: Cultural factors play a significant role in shaping the effectiveness of diplomatic negotiations by influencing communication styles, negotiation tactics, and the overall dynamics of interaction between nations. Different cultures bring distinct values, traditions, and social norms to the negotiation table, which can either facilitate understanding or create barriers to effective dialogue. For example, a negotiation approach that emphasizes direct confrontation may be effective in one cultural context but counterproductive in another that values indirect communication and consensus-building. Understanding these cultural nuances is crucial for diplomats to tailor their strategies, build trust, and achieve mutually acceptable outcomes in diverse international contexts.

Moreover, the recognition and respect for cultural differences can enhance the credibility of diplomatic efforts, as negotiators who demonstrate cultural sensitivity are more likely to build rapport and secure the cooperation of their counterparts. By incorporating cultural considerations into negotiation strategies, diplomats can create an environment of respect and collaboration that fosters more productive discussions. This approach not only improves the immediate outcomes of negotiations but also lays the groundwork for long-term international relationships that are based on mutual understanding and respect. The integration of cultural factors is thus essential for the success of diplomatic initiatives in an increasingly globalized world.

10. How can the principles of soft power be applied to enhance diplomatic strategies in the 21st century?

Answer: The principles of soft power can be applied to enhance diplomatic strategies in the 21st century by leveraging cultural influence, education, and public diplomacy to shape international perceptions and foster cooperative relationships. Soft power emphasizes attraction rather than coercion, encouraging countries to use their cultural assets, values, and institutions to build goodwill and influence global opinions. In practice, this might involve promoting national culture through arts, sports, and academic exchanges, as well as utilizing digital platforms to engage with foreign publics and share positive narratives. By effectively employing soft power, nations can create a favorable environment for diplomatic negotiations, reduce tensions, and build strategic partnerships that enhance global stability.

Additionally, soft power strategies can complement traditional hard power approaches by providing a more holistic framework for international relations. When used in conjunction with economic and military capabilities, soft power enhances a nation’s overall influence and bargaining power on the global stage. It enables governments to address issues like human rights, environmental protection, and democratic governance in ways that resonate with diverse audiences. As such, integrating soft power into diplomatic strategies is essential for promoting a more cooperative and peaceful international order in the 21st century.

11. How might emerging challenges in international law affect the practice of cultural diplomacy?

Answer: Emerging challenges in international law, such as cybercrime, climate change, and transnational terrorism, are likely to affect the practice of cultural diplomacy by necessitating new legal frameworks and collaborative approaches among nations. Cultural diplomacy, which traditionally relies on soft power and non-coercive engagement, may need to adapt its methods to operate effectively within a rapidly evolving legal landscape. As international legal norms evolve, cultural diplomacy can play a critical role in shaping these frameworks by promoting dialogue and mutual understanding across borders. For example, initiatives that foster cross-cultural exchanges could help to build consensus on international regulations for emerging issues, ensuring that legal standards reflect a broad range of cultural perspectives.

Furthermore, emerging challenges may require cultural diplomats to navigate complex legal environments that involve balancing national interests with global obligations. This could lead to the development of innovative public diplomacy strategies that align with international legal standards while preserving cultural identity and sovereignty. By engaging with legal experts and international organizations, cultural diplomats can contribute to the formulation of new norms and treaties that address these challenges. Ultimately, the integration of cultural diplomacy with evolving international law will be essential for promoting global cooperation and addressing transnational issues in a manner that respects both legal and cultural diversity.

12. How might the role of public opinion shape the future of cultural diplomacy and international relations?

Answer: Public opinion is increasingly shaping the future of cultural diplomacy and international relations by exerting pressure on governments to adopt more transparent, inclusive, and responsive diplomatic practices. In today’s interconnected world, citizens have greater access to information and are more engaged in global affairs than ever before. This heightened awareness means that public opinion can significantly influence diplomatic priorities and strategies, driving initiatives that promote cultural exchange, human rights, and international cooperation. When governments are responsive to public sentiment, cultural diplomacy becomes a powerful tool for building trust and legitimacy, both domestically and internationally.

Furthermore, the rise of social media and digital communication platforms has amplified the impact of public opinion, allowing grassroots movements and civic organizations to shape international narratives. As these voices become more prominent, they compel policymakers to consider cultural and ethical dimensions in their diplomatic engagements. This evolving dynamic may lead to a more participatory form of diplomacy, where public input is actively sought and integrated into international decision-making processes. Ultimately, the influence of public opinion will continue to redefine the landscape of cultural diplomacy, making it an essential component of effective and responsive international relations in the future.